PARK SLIP. Tondu, Glamorganshire. 26th. August, 1892.

Park Slip Colliery was the property of Colonel Norton’s, North’s Navigation Collieries (1899) Limited and was near Tondu on the Llynfi and Ogmore Railway where it passed over the southern outcrop of the South Wales coalfield. The line of the outcrop is from Llantrisant on the east to Port Talbot on the west where the coal basin entered the Bristol Channel. Few collieries had been established along this outcrop but small-scale workings had been worked along this line for more than 100 years before this disaster. In 1770 a colliery was started at Cefn, about a mile to the west and in 1834 another was opened at Bryndu about 2 miles to the west of Park Slip. Morfa colliery when there was an explosion in 1890 with the loss of 87 lives lay about seven miles to the west. Some shafts had been sunk to the east of Tondu but the seam there is practically untouched. Park Slip was on the edge of practically virgin coal and was commenced in 1864 and has been working since then to the explosion.

The seams at the colliery dipped sharply to the north at an average inclination of 1 in 2.13. The main seams worked were the North Fawr, ten feet thick, the South Fawr, five feet thick, the Four Feet four and a half feet thick, the Six Feet, the Nine Feet, the Five Quarter five and a half feet thick, the Cribbwr of the same thickness and the Cribbwr Fawr, two and a half feet thick. All the seams, with the exception of the Four Feet and the Cribbwr Fawr, had been worked to some extent and at the time of the disaster, only the North Fawr and Cribbwr seams were being worked.

Mr. James Tamblyn was the certificated colliery manager who acted for the agents and the owners and had the general supervision of all the Company’s collieries including Park Slip. Mr. James Willis Davison was the certificated manager of the colliery and had held the position for about two years. He lived near the pit. Griffith Roberts, who held a second-class certificate, was his undermanager and the day shift overman. Messrs. Forster Brown and Rees, mining engineers of Cardiff, acted as consulting engineers for the owners at their collieries.

The seams were won by two parallel drifts, fifteen yards apart in the Five Quarter Seam which appeared at the start of the colliery were chosen since they would have a better roof. One of these drifts was known as the “slip” and was used as the main haulage road and the main air intake. The other was known as the “horseway” and was the main return and contained the pumps used for the drainage of the workings. At intervals of 100 yards or upwards on the slip, were stages where communication by cross-measure drifts had been made with the other seams at different points where these had been worked. These were situated as follows. From surface to No.1 stage 277 yards but this was not working from the surface to No.2 stage, 385 (not working), from the surface to No. 3 stage, 508 yards, (not working) No. 4 at 623 yards, No. 5 at 742 yards (not working), No. 6 at 863 yards, No. 7 at 1,030 yards and No. 8 at 1,166 yards.

The North Fawr Seam had been worked from stage No.2 but at the date of the explosion, it was being worked from stages Nos 2 and 4. The South Fawr Seam had been partially worked from No. 2 and 4 stages but abandoned and the Six Feet had also been abandoned after being worked from No.2 stage. A little of the Five Quarter had been worked from Nos.2 and 3 stages and abandoned. In the Cribbwr Seam, there were extensive workings from the Nos. 1, 2 3, 4, and 5 stages and at the time of the explosion, it was being worked from the Nos. 6, 7, and 8 stages.

The haulage in the main slip of the Cribbwr Seam was done by an engine at the surface by two wire ropes which was double for half its distance and an empty train was lowered while a full one was raised. Ten trams, each containing 9 to 10 cwts of coal were drawn at a time. The trams that were used were of the type that was common in the Welsh steam coal collieries and was similar to the box trams used in the north of England where the inclines were very steep. The haulage done on the level headings was done by horses of which there were 16 in the colliery. The trams were raised and lowered between the two-level headings and the working places by means of short self-acting inclines known as “jigs”.

In 1889, the longwall method was started in the Cribbwr Seam on the west side in the No.7 range which was then the lowest working stage but the old method was still in use in the seam in the Nos. 6 and 7 east where pillars were in the course of removal and in the North Fawr Seam worked from No.4 stage where pillars were being formed. In both systems, the coal was won by narrow, narrow with pillars between. In No.7 west, the longwall had been commenced 80 yards above the level heading. At the time of the explosion, only a small area of coal was left in this heading. In the longwall system, the whole of the seam is removed in one operation, the necessary roads being maintained through the goafs by means of pack walls. The roof immediately behind the face is supported by props and the goaf filled with rubbish packing that was brought for this purpose.

In 1890 the main slip was extended from No.7 to No.8 range and the Cribbwr Seam was won in this range at a total distance on the slope of 1,166 yards from the mouth of the drift. The surface above No.8 range was 160 feet higher than the mouth and the total vertical depth from the surface here was 584 yards. Owing to water getting into the upper ranges, the main slip was for a time, underwater below No.7 stage and this was opened at the start of 1892.

No.8 range was opened by the usual narrow work and two weeks before the disaster it was decided by the agent and manager to start a longwall on the west side. The pair of headings had been driven about 200 yards and some stalls some distance to the rise of the upper headings had been completed. It was also decided to start the longwall from the upper heading, 20 yards above the main level heading instead of 40 yards above as had first been projected. At this time no communication had been made with No.7 heading. This stall was intended to be used to bring down rubbish to stow in the walls. This was just beginning at the time of the explosion.

All the workings produced firedamp but there was no reason to suspect that the ventilation was other than adequate or that accumulations of gas were a frequent occurrence. The examination of the firemen’s books for the three months before the explosion showed that gas had been found on several occasions during July and August. The colliery was dry and dusty in some parts and wet and damp in others. All parts of the colliery were swept by the flame of the explosion which contained coal dust and ceased in places where there was no coal dust.

The ventilation was provided by a Schiele fan, 11 feet in diameter which was placed near the top of the main return and ran at 23 revolutions per minute. The current passed down the main slip and split at different stages. Each split was conducted along the lower of the main heading from the furthest point in the respective ranges and then to the rise, ventilating the working places and returning by separate return airways to the main return. On August 19th 1892 28,649 cubic feet per minute were passing through the mine at a water gauge of 2.9 inches.

Both the North Fawr and the Cribbwr Seams were worked with safety lamps the majority of which were “Cambrian” or bonneted Clanny lamps and the remainder were ordinary Clannys with movable tin shields placed around the gauze. They were locked by an ordinary screw lock. The lamps were the property of the workmen, each of whom took home the case, the top portion including the gauze, to be cleaned and the oil vessel was left at the colliery lamp room to be supplied with the necessary wick and oil. In the morning two fireman in the lamp room examined the cases as they were handed in by the workmen and the lamp man and his assistant screwed in the oil vessels and recorded in a book the mark opposite the name and number as each lamp was handed back to their owners. The statutory examination and locking of lamps for the day shift took place in the mine by the firemen at appointed stations near the entrance to Nos. 4, 6 and 7 districts and there were re-lighting stations at various places in the mine during the shift. The “competent” persons appointed to attend these stations and the locking of lamps at the stations were hitchers employed in looking after the trams at the stages. A lamp key attached to a small chain to a prop was sued for opening and closing the lamps at each station. Open lamps, “Comet” oil lamps, were used at nos. 4, 6, 7 and 8 stages.

Blasting in the coal had been discontinued for some years but at one time it was done regularly in the Cribbwr seam to get coal. Shot firing was allowed for driving the cross-measure drifts to the different seams and for taking the hard bottom stone in the Cribbwr seam headings. The only heading advancing in these conditions was the No.8 range and some blasting had taken place there some weeks before the disaster. Two additional stalls for the horses were being constructed in the No.8 west heading and blasting was necessary to do this to remove the bottom stone. The shots were fired on the night shift and the last shot had been fired at 11.30 p.m. on 25th August.

The person authorised to fire the shots were the overmen and firemen and the leading man in each of the two main headings in No.8 range. According to the instructions of the agents and the manager, all shot firing was done between shifts. These instructions were not carried out on the night shift but there was no evidence to show that shots had been fired on the day shift. The explosives used were cartridges of dynamite and gunpowder. Shots were fired by a fuse which was lit from an open lamp. Water could be obtained from “slip” in this range and there were casks of water which could be used under General Rule 12 but this seemed to have been down in a perfunctory manner, if at all.

There was one principal shift of colliers during the day and a repairing shift with a few colliers during the night. The day shift, comprising about 165 men, began to descend at 6 a.m. and ascended about 5 p.m. The night shift of 45 men went down at 5.30 p.m. and came up at 3 a.m. The output of coal was about 280 tons per day.

There were five firemen during the day shift. Three of these went down at 3.30 a.m. and examined the working places and roadways before the shift commenced as required by the 4th General Rule of the Coal Regulation Mines Act 1887. The other two firemen went down with the last of the men at about 7 a.m. and remained until all the men were up. Written reports were made by the firemen down the pit and sent up to the colliery office every morning. Every working place was inspected twice a day and this was in addition to an inspection made by the undermanager every morning. During the night shift, there was an overman who performed or as intended to perform the duties of the firemen during the shift. The night overman also took the duties of the “competent” person to lock the lamps at No.4 stage. The examination before the night shift commenced was made by the day firemen.

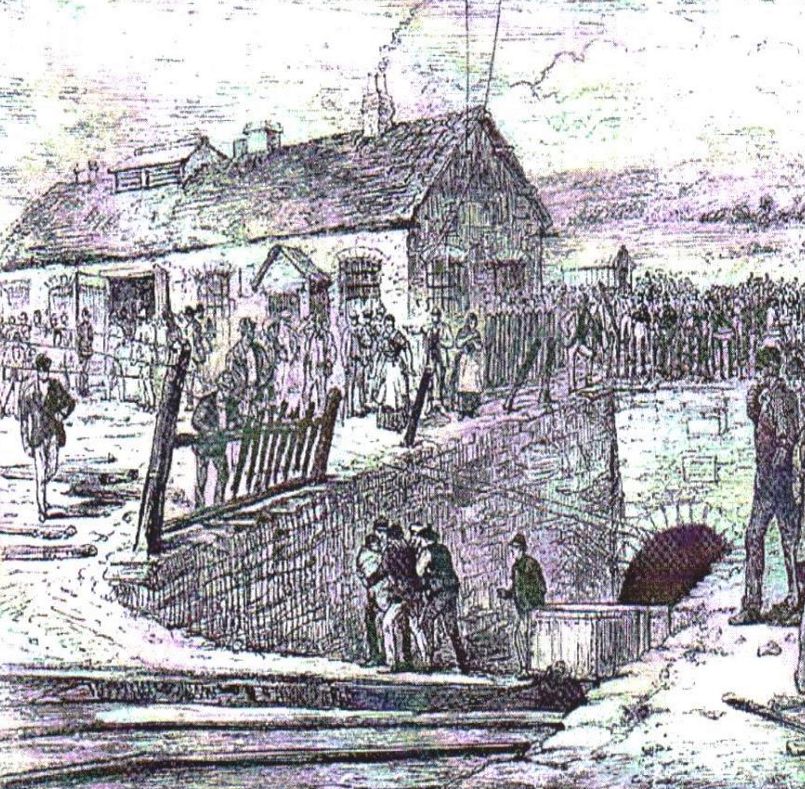

The explosion took place at 8.30 a.m. on Friday 26th August within two hours of the start of the shift when 151 men and boys were underground. Work appeared to have been going on as usual without any known obstruction or derangement when those at work on the surface were startled by the explosion. A large cloud of dust, followed by flames shot out of the mouth of the slip or the intake airway, closely followed by dark smoke. A loud report was heard within a second or two according to the engineman’s testimony. Stones debris and burning material were thrown from the mouth of the slip. The blast broke nearly all the panes of glass in the fan house, the office windows and other buildings nearby. A disused fan house was damaged and the roof of the pumping engine-house, which was 38 yards from the mouth of the slip, was set on fire by the burning material that came from the mouth of the slip.

The manager was in the office at the time and steps were immediately taken to recover the mine and the men who were in it. Fortunately, the fan was not damaged and the means to restore the ventilation was available. There were soon large numbers of men willing to help with the work of exploration and this was carded on as long as there was a possibility of saving a life.

Telegrams for help were sent to Maesteg and colliers assembled at the pit top and volunteered to go down as soon as parties of explorers could be organised. Mr. Robson, Inspector was on leave but went to the colliery when he received a telegram informing him of the disaster and he arrived at 10 p.m., three Assistant Inspectors in the South Wales District, Messrs. F.A. Gray, J. Mancel Sims and J. Dyer Lewis were all soon at the colliery. During the whole of the time the explorations were going on at least one of the Inspectors remained at the colliery day and night and made frequent visits underground and after the mine had been secured they were able to make a detailed inspection of the workings with the exception of the North Fawr which was not re-opened but was inspected.

Soon after the disaster two pumpmen, who had been working in the main return, 60 yards from the surface, were rescued alive and uninjured although they had encountered the afterdamp. As the exploration continued, it was found that very many heavy falls had taken place in the main slip. One of these falls blocked the way completely and had to be cleared. This was partially done so that the explorers could go into the workings. The Inspector commented that:

This block in the intake led to some well-meant by terribly risky efforts to reach the stages by way of the main return, which contained a large amount of afterdamp.

It was soon found that the doors separating the main intake and return were blown to pieces. These 19 openings between the top and the bottom had to be closed temporarily to get the air current downwards. This work caused a considerable delay as getting materials to the various places was most laborious as they had to be dragged over the huge falls.

During the day No.4 stage was reached and the bodies of fourteen men and boys found within 50 yards of the stage. It was then impossible to penetrate into the drifts leading to the North Fawr as it was entirely blocked by a fall about 90 yards from the entrance and the return as so full of afterdamp that no one could pass through. With six exceptions, all the bodies that were found there were those of men who had run out from the workings on the North Fawr but the return airway and it was feared that there could be no one left alive in these workings.

Before 6 a.m. the following morning, the bodies of several others had been reached at or near the Nos. 6 and 7 stages and on the heading leading from these points. No sign of life had been discovered. The efforts of the explorers to restore the ventilation was rewarded after a few hours and before noon 18 men and lads, many of them little the worse for their long imprisonment, came out from the North Fawr workings by way of the return. A little later 25 others were found alive in No.7 West heading but two of these died almost immediately afterwards. At least seven of the others were unconscious and had to be carried up the steep incline over 1,000 yards and over rugged falls. Four of them never rallied and died within a day or two. Some of the doctors were reported to have gone down the mine and they did all that could be done for the stricken men.

By Saturday evening the Cribbwr Seam had been explored except for a few places which were found to be filled with firedamp so that none could have survived in that atmosphere. The North Fawr workings had not been examined but it was known that all those who were working there had been accounted for. By the 5th September all the bodies had been recovered with the exception of two and the recovery of these was delayed by the flooding of the No.8 range due to the stoppage of the pumps. After the water was pumped out the body of John Curtain was found under a large fall at the face of the east level heading and that of George Dunster on the slip between Nos. 7 and 8 ranges on the 20th September.

Of the 151 people in the mine at the time of the disaster, 39 were saved and 108 were killed in the initial blast. Four were rescued alive but later died, making the total death toll 112. Of the sixteen horses in the pit, all were killed.

Names of the persons who were in the mine when the explosion occurred are recorded in the Official Report.

In the Main intake and Return:

- Henry John aged 44 years, pumpman. Came out alive,

- Henry Belcher aged 22 years, pumpman. Came out alive,

- George Edwards aged 42 years, roadman. Found dead,

- David Major aged 45 years, pumpman. Found dead,

- George Lowman aged 38 years, repairer. Found dead,

- John Lovell aged 43 years, repairer. Found dead,

- David Powell aged 42 years, repairer. Found dead,

- James Davies aged 52 years repairer. Found dead,

- John Harry aged 28 years, repairer. Found dead,

- George Dunster aged 29 years, roadman. Found dead,

- Charles Nicholl aged 18 years, switchman. Found dead.

In the No.6 District. All were found dead:

- Thomas Cockram aged 37 years, collier,

- John Cockram aged 35 years, collier,

- Eli Howell aged 22 years, haulier,

- Lewis Cockram aged 28 years, collier and

- Jonathan Harry aged 26 years, fireman.

From the No.7 District, the following came out alive:

- Thomas Rees aged 25 years, collier,

- Jenkin Rees aged 31 years collier,

- Evan Richard aged 38 years, collier,

- Frank John aged 30 years, hitcher,

- William Nicholls aged 20 years, hitcher,

- David Howells aged 24 years, collier,

- David Potter aged 38 years, collier,

- Edward Mordecai aged 36 years, collier,

- Thomas Watkins aged 24 years, collier,

- John Davies Jnr. aged 17 years, filler,

- William Richards, contractor,

- James Lyddon aged 23 years, collier,

- Roberts Williams aged 46 years, collier,

- William David (Noah) aged 24 years, collier,

- George Rees aged 57 years, repairer,

- Thomas Thomas Jnr. aged 18, filler,

- David Phillips aged 34 years, collier,

- John Thomas aged 14 years, haulier,

- John Granville aged 32 years, collier,

- Thomas Thomas Snr. aged 41 years, collier. Died August 31st 1892,

- Evan Hopkin aged 15 years, hitcher. Died August 29th 1892,

- Henry Strike aged 32 years, collier. Came out alive. Died 28th August 1892,

- David Daniels aged 18 years, trammer. Came out alive. Died 28th August 1892.

- Those found dead in the No. 7 District:

- David Hopkin aged 15 years, haulier.

- Harry Lyddon aged 20 years, slip hitcher.

- Griffith Roberts aged 41 years, overman.

- William J. Painter aged 16 years, haulier.

- Henry Mitchell aged 49 years, labourer.

- Arthur Martin aged 42 years, collier.

- Jenkin Jenkins aged 35 years, collier.

- Fred Roberts aged 22 years, collier.

- John Berwick aged 21 years, collier.

- Morgan Morgan aged 16 years, jig hitcher.

- George Davies aged 14 years, haulier.

- D. Davies aged 23 years, collier.

- Richard Davies aged 21 years, collier.

- John Thomas aged 57 years, repairer.

- Thomas Carter aged 18 years, collier.

- James Lyddon aged 30 years, collier.

- George Henson aged 22 years, hitcher.

- Thomas Lukins aged 46 years, collier.

- R.H. Webster Snr. aged 41 years, collier.

- Elijah Driscoll aged 15 years, haulier.

- Phillip David Snr aged 54 years, collier.

- James Painter aged. 19 years, jig hitcher.

- Alf Burrows aged 20 years, collier.

- Evan David aged 27 years, collier.

- John Orchard aged 43 years, collier.

- George Cockram aged 40 years, roadman.

Those found dead in the No.8 District:

- James Richards aged 17 years, trammer.

- George Talke aged 28 years, collier.

- John Roberts aged 16 years, trammer.

- Thomas Baker aged 40 years, collier.

- Thomas Jacobs aged 18 years, jig hitcher.

- Henry Hurley aged 25 years, collier.

- Charles Stenner aged 39 years, collier.

- David Jones aged 14 years, trammer.

- William Lyddon aged 22 years, collier.

- Thomas Taylor aged 39 years, collier.

- Thomas Rees aged 35 years, collier.

- Evan Morgan aged 18 years, slip hitcher.

- Thomas Williams aged 17 years jig hitcher.

- Thomas Stenner aged 37 years, fireman.

- John Osborne aged 63 years, labourer.

- Rees Thomas aged 17 years, collier.

- John John aged 57 years, repairer.

- William Williams aged 38 years, collier.

- Elias Howells aged 28 years, collier.

- John Gibbon aged 31 years, collier.

- Lewis Davies aged 22 years, collier.

- William Davies aged 48 years, collier.

- George Jacob aged 40 years, collier.

- Herbert Lyddon aged 18 years, collier.

- Ben Davies aged 24 years, collier.

- William Stenner aged 45 years, collier.

- John Driscoll aged 21 years, collier.

- John Curtain aged 31 years, collier.

Those who came out alive from the No.4 District were:

- Dan Fitzgerald aged 18 years, trammer.

- George Mynet aged 23 years, trammer.

- John Mynet aged 20 years, hitcher.

- John Lyddon aged 17 years, trammer.

- Thomas Jones aged 31 years, jigger.

- Thomas Bennett aged 31 years, jigger.

- Donald Strandling aged 58 years, repairer.

- James Berwick Jnr. aged 16 years, filler.

- John David aged 28 years, collier.

- Edward Thomas aged 37 years, collier.

- Donald Davies Jnr. aged 24 years, collier.

- Levi Bowen aged 19 years, collier.

- William John (Tyn-pwnt) aged 18 years, labourer.

- Thomas Smith aged 17 years, jigger.

- Donald Halliday aged 16 years, filler and trammer.

- James Barnett aged 24 years, collier.

- John John (Tyn-pwnt) aged 19 years, jigger.

- Donald John (Tyn-pwnt) aged 21 years, trammer and filler.

Those who were found dead in the No.4 District were:

- D.R. Jones aged 15 years, haulier.

- Donald Thomas aged 15 years, haulier.

- Thomas Hopkin aged 36 years, fireman.

- William Williams aged 50 years, contractor.

- Herbert Sanders aged 25 years, collier.

- Thomas Webster aged 23 years, slip-hitcher.

- Thomas Daniel aged 21 years, trammer.

- James Berwick sen. aged years, collier contractor.

- Gwillym Williams aged 45 years, fireman.

- Edward Humphries aged 21 years, trammer.

- Thomas Williams aged 27 years, collier.

- E.R. Jones aged 17 years, trammer.

- James Bowen aged 46 years, contractor.

- David Harry aged 30 years, collier.

- John Rosser aged 22 years, collier.

- Thomas H. Henderson aged 18 years, hitcher.

- Edward Down aged 38 years, collier.

- James Gibbs aged 19 years, collier.

- James Evans aged 23 years, collier.

- George Lyddon aged 21 years, collier.

- Enoch Davies aged 22 years, collier.

- Thomas Williams aged 20 years, collier.

- David Bowen aged 13 years, trammer.

- Richard Davies aged 28 years, collier.

- David Jones aged 18 years, collier.

- William Rosser aged 18 years, collier.

- Ivor Thomas aged 18 years, collier.

- Thomas Hopkin aged 16 years, haulier.

- David Davies sen. aged 51 years, contractor.

- Albert Lyddon aged 26 years, collier.

- David Powell aged 22 years, collier.

- Thomas Jones aged 25 years, collier.

- R.H. Webster Jnr. aged 19 years, hitcher.

- Henry Barnett aged 28 years, collier.

- Christopher Warren aged 19 years, collier.

- John Chappell aged 26 years, collier.

- Lewis Morgan aged 58 years, roadman.

The Queen telegraphed a message of sympathy to Her Inspector and the Lord Mayor of London opened a subscription fund to relieve the dependents of the victims.

The inquest into the deaths of the men was held before Mr. Howell Cuthbertson, Coroner and a jury at Aberkenfig from the 4th October to the 9th November. All interested parties were represented. The inquiry was searching and exhaustive and many points of the working of and the discipline in, the colliery prior to the explosion were raised. After hearing all the evidence the jury retired and returned the following verdict:

We find that the loss of life at the Park Slip Colliery on August 26th, 1892 was caused by an explosion of gas and it’s after-effects. That the explosion took place in the longwall top of No.2 jig, west of No.8 district but by what means the gas was ignited, there is no evidence to show.

The ventilation according to the evidence was fairly good. The arrangement for leaving keys at the lamps stations is not commendable, but the practice being in force before the present manager’s time, and also at other collieries, we attach no blame to anyone.

We also recommend that the Mines Regulation Act be so altered as to make compulsory the watering of the sides roof and floors wherever that are dry or dusty and that no short firing should be allowed in any circumstance, except between the shifts, Further that all lamps should be the property of the employers and never taken from the colliery by the workmen, so as to allow proper supervision at the lamp room.

We also recommend that all workmen should be searched for matches, keys, etc. before they enter the workings on every occasion.

In the official report, the Inspector commented that he was pleased to see that the jury recognised coal dust a serious factor in this disaster. He was of the opinion that the pit of ignition had taken place on the east side and not the west and that the quantity of air to the working could have been more and proceeded to offer recommendations which included that no torchlight whatsoever should be allowed in the mine, that the use of gunpowder and dynamite should be prohibited, that in the night shift, there should be a fireman as well as an overman and that a system of watering the roadways similar to that employed in neighbouring collieries should be adopted.

REFERENCES

The Mines Inspectors Report.

Reports on the explosion at the Park Slip Colliery, in the South Wales District by A. Young, Esq., Barrister-at-Law and by J.P. Robson, Esq., and W.N. Atkinson, Esq., Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Mines.

The Colliery Guardian, 11th November 1892, p.877.

The Illustrated London News.

“And they worked us to death” Vol.2. Ben Fieldhouse and Jackie Dunn. Gwent Family History Society.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

Return to previous page