UNIVERSAL. Senghenydd, Glamorganshire. 14th. October, 1913.

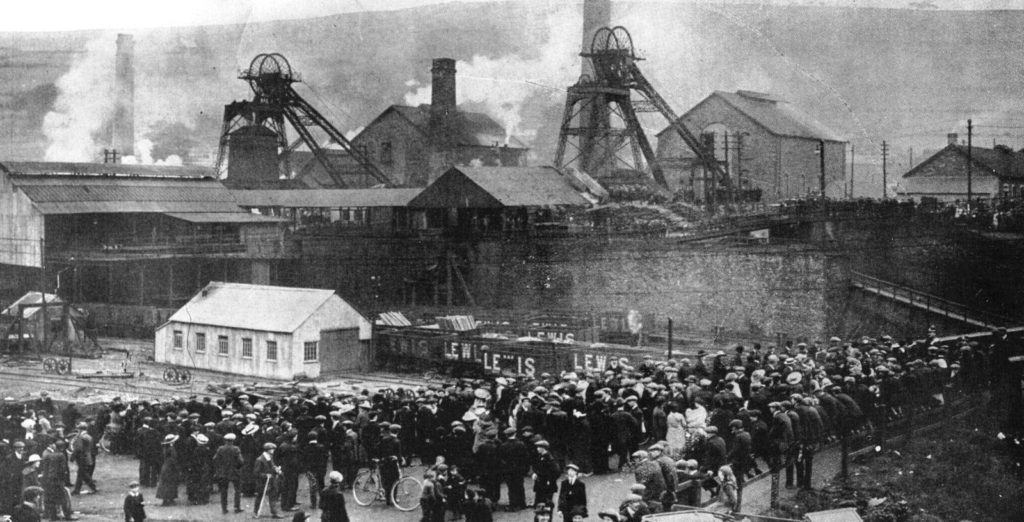

Crowds await news at the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd

Photograph from The Illustrated London News of 18 October 1913 (issue 3887; page 4). Article titled “The Burning Pit Disaster: Rescue Scenes at the Universal Colliery”.

The explosion was the worst in the history of British mining. Four hundred and thirty-nine men and boys were killed in the explosion or died from the effects of the afterdamp and one man lost his life the following day by a fall of stone while he was fighting a fire on the Main West Level. The Universal Colliery was at the head of the Aber Valley, Glamorganshire and was about 12 miles as the crow flies from Cardiff. The colliery was owned by The Lewis Merthyr Consolidated Limited and Mr. Edward Shaw was the Agent and manager of the colliery. he had been manager for 12 years and agent for the last four. under him were two managers, one for the East Side and one for the West. On the West Side there were three overmen, one each for the Kimberley and Ladysmith districts, one for the Mafeking and one for the Pretoria. Under them there were 14 firemen. On the day shift Edward Jones was fireman in the Pretoria which had 27 working places and a total of 79 men, colliers, hauliers, wallers, repairers and others. D.T. Edwards was sin the East Ladysmith with 20 working places and 23 men, Rees Thomas in the West Ladysmith with 28 working places and 89 men, Evan Jones in the Kimberley with 18 working places and 50 men, W.H. Childsley in the West Mafeking with 46 working places and 125 men, Fred William also in the West Mafeking with 11 working places and 31 men and John Jones in the Bottanic with 17 working places and 54 men.

On the night shift, Richard Davies was the fireman in the Pretoria district which had 6 working places and he had charge of 55 men, John Skym in the East Ladysmith with 13 working place and 29 men, Morris Roberts in the West Ladysmith with 3 working places and 46 men, Ben Thomas in the Kimberley with 4 working places and 37 men, Richard Davies in the West Mafeking with two working places and 18 men along with James Opie in the same district with 9 working places and 48 men and Nic Sands in the Bottanic with 7 working places and 36 men.

The day firemen went down at 3.30 a.m. and ascended at 1.00 p.m. while the colliers and others went down between 5.10 to 6 a.m. and cam up at 2 p.m. Coal drawing was carried on from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. and the firemen on the repairing shifts went down with their men and stayed with them. The day shift went down at 2 p.m. and came up at 10 p.m. and the night shift went down at 9 p.m. and ascended at 5 a.m. The firemen who went down at 3.30 a.m., went down two hours before the men and made their statutory examination of the working places. They then went to the pit bottom and met the men at the lamp locking stations. The Act stated that the workings had to be inspected not more than two hours before the commencement of the shift. At most collieries in the country, there were meeting stations in the district which were a short distance from the face but at Senghenydd there was only one station for the whole of the west side and that was 440 yards from the shaft bottom. In the majority of cases the men they had to walk 1,300 yards to the first place.

William Chidsey, a fireman in the Mafeking District, said that it took him twenty minutes to get from the lamp station to the working face of his district, forty minutes to travel in and out again which left one hour twenty minutes for the inspection of the workings in his district. he had 44 stalls to examine and claimed that he could do this in the time. At the inquiry, the Commissioner, Mr. Redmayne, had serious doubts about this. A similar story was told by Morris Roberts, a night shift fireman, and John Skym, a fireman in the Ladysmith District, which led the Commissioner to the conclusion that the Rules were being breached.

The shafts had been sunk about 23 years previous to the accident and coal had been worked since 1896. There had been a serious explosion at the colliery on the 21st. May, 1901 and there were no firm conclusion as to the cause. Mr. S.T. Evans concluded in the report no hat disaster by pointing out the importance:

That provisions should be made for the preventing the accumulation of coal dust and for the regular and efficient watering of the roads, roofs and sides in the main haulage and travelling ways in mines which are dry and dusty.

The seams that were worked at the colliery were the Four Feet, the Universal and the Nine Feet. The underground workings were divided into two main divisions, the West Side and the East Side. The Four feet was worked on the West Side and the Four Feet and the Universal, and the Nine Feet were worked in the East Side and all theses workings were connected to one level by drifts. There were two shafts, the Lancaster which was a downcast and the York which was the upcast. Both were 18 feet 6 inches in diameter and the depth from the surface to the Six Feet landing was 535 yards from which most of the coal was drawn. They were sunk to 650 yards and the York Pit also had a heading to the Nine Feet Seam. Coal was wound from both shafts with the Lancaster shaft winding the majority. The bottom of each shaft was arched with masonry and the arching on the west side in the Six Feet landing extended for 124 yards from the shaft. A block of coal had been left to support the shafts, 500 yards in diameter and spread over forty-two and three-quarter acres.

The coal was worked by the longwall system, the width of the stalls being eleven yards from centre to centre. very little timber was withdrawn and recovered as it was customary to leave the timber in the gob in South Wales. Mr Redmayne commented:

Of course, the best practice both from safety and the economic point of view, is to take out the timber from the gob, but under poor roofs where the gods are stowed with rubbish right across the face, it may be impossible to do this and Mr. Shaw stated that at Senghenydd the roof broke immediately behind the face, that the goaf close tight and there was always regular settlement and further that the character of the roof stone is such that little timber can be withdrawn. The even settlement of the goaf is desirable in the interests of safety, and the tighter the goaf is, the less unventilated space there is for accumulation of firedamp.

No explosives were used in getting coal and for rippings in ground that was particularly hard, which was a rare occurrence in this mine, Robertite was used and the shots fired by authorised shot firers. No blasting was carried out on the day of the explosion and no shots had been fired since the previous Sunday, October 12th.

The colliery produced about 1,800 tons of coal per day which was filled into waggons which were of the common Welsh type, which were open at each end but for a bar and the coal piled well above the top of the trams. The main haulage from the Mafeking, west York, Botttanic and part of the No.2 South (Pretoria) Districts was carried out in the return airways. Only the main haulage from the Kimberley and Ladysmith Districts was entirely in the intake. Mines which were opened before the Coal Mines Act, 1911, were exempt from the requirements of Section 42 (4) which stated that, “where the air current in the main return airway was found normally to carry than half of one per cent of inflammable gas, that airway shall not be used to haul coal.” Under the requirements of the Coal Mines act. 1911, “no tram for the conveyance of coal can be introduced into a mine after that date of the passing of the Act unless it is so constructed and maintained as to prevent as far as practicable coal dust escaping through the sides end or floor of the tram and after a period of five years from 16th. December 1911, all trams whether old or new, have to conform to this requirement.”

The management of the colliery were gradually putting this requirement into effect but before the act came into force and had already ordered a few hundred trams that were closed at both ends.

The trams ran on a track which was 3 feet gauge and each weight about 8 or 9 hundredweights, the average weight of coal transported in each was 26 hundredweight. the secondary haulage was performed by horses but in a few cases mechanical haulage was fed right up to the face in the Pretoria and Ladysmith Districts. The width of the secondary haulage was about seven feet and the main haulage was carried out by compressed air engines throughout the mine and there were a large number of these engines. In some places haulage was carried out by gravity as was the case in the Mafeking incline. the rate of haulage was from 4 to 8 miles per hour and a journey usually consisted of 24 trams.

An electrical system was used forth signalling and there were a number of sets of signalling equipment throughout the colliery, over a dozen in all. each set consisted of a trembler bell which was protected by a cast-iron cover but was not gas-tight and a battery of six to nine dry cells of the “Dania” pattern delivered about 1.5 volts per cell and two bare wires which were described as No.8 galvanised steel wires supported on insulators which in turn were secured to the side timbers. The wires were run 12 to 18 inches apart on the same side of the roadway. The bells and batteries were in the engine houses. Every time the wires separated after having been brought together or bridged across with a knife of file to give a short circuit to give short sharp rings on the bell, sparks would be formed and every time a bell was run there would be a succession of sparks at the make and break contacts under the bell cover.

The mine was ventilated by a Walker “Indestructible Fan” which was placed at the surface and driven by a steam engine. the fan was 24 feet in diameter and exhausted from the York shaft and was driven at a speed of 47 r.p.m. which sent 200,000 cubic feet per minute at a water gauge of 2.3 inches. of this, 152,000 cubic feet entered the West side. The manager said that the fan was capable of producing more air, 400,000 cubic feet at a water gauge of 4 inches. There were arrangements for reversing the air current as was required by the Act, but the work had not been completed. It would take about two hours to effect air reversal of the air. this requirement was to have been operative by 1st. January, 1913 but in April, the owners applied for an extension to allow them to make certain structural alterations and the Inspector extended the period which finished on the 16th. September. The termination was further postponed until 30th. September. This work had not been completed and the counsel for the owners and manager at the inquiry admitted that they were guilty of contravening Section 31 (3) of the Coal Mines Act, 1911.

The book in which the record of the air measurements were recorded was not in the form which the Secretary of Stare prescribed and was not signed or counter-signed by the manager and undermanager. The mine generated large volumes of inflammable gas and according to measurements taken by the Mines Inspectors after the explosion, about 1,200 cubic feet per minute were being produced. There had been occasions when there had been large, sudden outbursts of gas when the men had had to be withdrawn. Cambrian safety lamps made by Messrs Thomas and Williams, with a lead rivet lock, were supplied for used throughout the mine. The manager was under the impression that these lamps were approved under the 1911 Act. In this he was mistaken, the lamp had been approved but the lamps were fitted with an unapproved glass. The lamps were lighted, locked and issued to the men at the surface and were again examined underground at “locking stations”. These were cabins on the West and East side, situated a little distance from the shaft and just off the main intake airway. the lamps were examined here by firemen when meeting the incoming shift. if anyone lost his lamp he would have to outbye to the lamp cabin to relight it. This was done by “lamp lockers” who were authorised by the manager to perform this work. There was no written authority from the management as was required by the Act.

The screens were about 80 yards from the top of the downcast shaft and there was little coal dust carried down the shaft from the surface but some would have blown off the ascending full tubs. The open ends of the trams and the fact that they were piled high with coal were sources from which coal dust could arise and sets of tubs coming from the Kimberly, Ladysmith and No. 2 South (Pretoria) Districts were hauled against the air current thus allowing dust to be blown into the workings. There was only one wet stretch on the haulage road, which was outbye of the Ladysmith and the workings were generally dry and dusty. To deal with the dust problem, every afternoon and eight men were engaged in shovelling up the dust from the floor. As far as the manager could remember there were eight men engaged in this work, two in the Lancaster level from the shaft to the Kimberley face, and two in each of the Pretoria, Ladysmith and Mafeking districts. The whole length of the roads were not cleared every twenty-four hours, only the floor and the roof sides were not touched. Efforts had been made to clean the roof and sides but it was found impractical to remove the dust. When it was got down, either by brushing or comprised air, it was blown away by the air current and deposited elsewhere. Mr. Redmayne did not think that there had been enough effort to overcome the problem and there was yet another breach of the Act.

There were arrangements to water the mine and water was conveyed down each of the shafts in two-inch pipes. These were joined to one and a half inch pipes laid along the main haulage roads, fitted every 30 to 40 yards with a tap to which hose pipes were connected and the floors watered every night. The roof and sides were not watered and the watering of the floor beyond the end of the water pipes was done by water carts which were brought in on the haulage. the watering of the floors was well down and was inspected early in December, two months before the explosion.

As well as these efforts the tubs were sprinkled with water at the double parting in the Ladysmith, one at the entrance to the storage in Mafeking and one by the double parting in No.2 South. the sprinklers consisted of an upright pipe 5 to 6 feet high which was connected to the water pipes. At the top, there was a right angle piece who passed across the roadway. This was perforated to allow jets of water to play on the trams as they passed. In the Ladysmith trams had to pass 700 yards before they passed the water and, in the opinion of Mr. Redmayne, did little to suppress dust.

There was not a great deal of water available. The water was drawn from the Lancaster Pit at 60 gallons per hour, from the York Pit at 80 gallons per hour and from the sump at 558 gallons per hour. The latter was pumped to a wooden tank on the surface which also contained the water for the water jackets and the coolers for the air compressors. A pipe connected to the Caermoil Reservoir gave an additional 1,000 gallons an hour and the water along the roadways worked from the presser of this water.

The last inspection of the mine to be made and reported by the representatives of the workmen was made on 18th. August, 1913. They reported as follows:

We, the undersigned, examined the new 6 feet, York East. Found these districts free from gas and headings manholes in good order engines well fenced airways in good condition.

Ladysmith. We examined this district found Ladysmith in good order with the exception of a diluted blower in Martin’s Road main wanted a little cleaning and watering. Airways in good condition, also manholes and engines well fenced main wants dusting and watering.

Kimberley. Diluted blower in Downe’s Road 12 feet from rail airway and returns in good condition manholes and engines well fenced ventilation good.

Mafeking. Aberystwyth District. Diluted blower in William Thornton’s Road and in William Jones’s Road.

East Mafeking. Bottanic. Diluted blower in old road on right-hand side, also in the road near Ben Davies Barry but we all stopped until Ben Hill gets hole from No.1 North, from there to York West. manholes of the above two districts in good order, also the engines well fenced. ventilation also good. returns in good condition.

York West. Examined this district all in perfect condition, airways and returns in good condition, also manholes and engines well fenced.

Glawnant and East Side. Examined this district found diluted blower in Dd. Griffith’s Road, also in Richard Owen’s Road and, also in Evan Jones Road, everything in good order with the exception of these three places. ventilation very good airways and returns in good condition, also manholes and engines well fenced.

Slope. Examined this district found everything in good order. ventilation not perfect roads and airways in good condition, also returns manholes in good condition also engines well fenced.

Lower 9 feet left hand. Found the district in very good condition, free from gas, also roads very good except one part of the straight wanted watering and cleaning.

Straight. Found this district very good with the exception of Pikes Road diluted blower on this road, also in dd. Holland’s Road and Randall’s Road, roads very dusty and sides wanted cleaning airways and returns in very good condition, also manholes.

Pretoria. District No.2, South 9 Feet. Examined this district found everything in perfect condition, airways and returns also manholes.

Pretoria 4 feet. We examined this district found every place free from gas, well-ventilated airways, and returns in good condition.

(Signed)

THOMAS LEWIS.

When the explosion occurred on the morning of Tuesday the 14th. October, Mr. Shaw, the manager, was in the lamp room at the surface. At 8.10 he heard a report and at once went to the Lancaster Pit and saw that the surface around it was wrecked, the banksman was killed and the assistant banksman injured. Mr. Shaw found that the fan was still working and gave orders to a mechanic to set about taking the broken cage from the top of the downcast shaft and repairing the planking over the pit head. When this was done, Mr. Shaw and D.R. Thomas, the overman got into the cage n the upcast shaft. They examined the air for 50 yards and found that it was full of smoke and fumes.

Signals were coming from below ground and when others had arrived they went down the shaft. halfway down they saw the body of a man in a tram in the ascending cage with his legs hanging over the crossbars. The man had been blown into the tub at the pit bottom. They signalled to stop the cage and crossed into the other, pulled the body with them and continued their perilous journey. At the Six Feet Landing the cage jammed on bent girders. They shouted down to the Nine Feet landing where they found that the men from the East Side were all right.

They eventually got the bottom and they found a lot of smoke coming out of the return. they tried to get through the first cross-cut on the East side but the doors were burning fiercely so they went to the West side. There again there was arranging fire in the cross cut, the doors were blown towards the return and the timbering was burning but there was less woodwork on this side and the fire was not a fierce. They managed to put out the fire and got round to the Lancaster Pit where they found Ernest Moss, a shackler, alive behind some empty trams about four yards to the West of the shaft.

Crossing the pit, they found five or six men lying down full length, but all of them later died. these men were the hitchers and worked on the West side. Mr. Redmayne commented that it was odd that these men should have died and the banksman killed when Moses had lived. It was concluded that he must have been protected from the full effect of the blast and the explosion would have gained momentum in going up the shaft from the considerable quantities of dust that would have been blowing off the tubs.

The overman, D.T. Thomas, gave a clear and graphic account of his movement to the inquiry. He said that when he got into the Main West Level and worked along to the east, “It looked exactly like a furnace.” He was then told by the manager to go to the East side with a party of men whilst he and some others remained on the West side.

Shaw went along the Main West Level for about 40 yards to the hauling engine found the planking of the engine starting to blaze. He and others knocked down the planking and extinguished the fire. They went on to the crab engine and the timber there was on fire and every collar that I could see ahead was blazing. There had been no falls but the laggings just behind them were starting to give way. Mr. Shaw retraced his steps and joined Thomas and his party and helped them to put out the fire in the East side crosscut. He then tried to get into the Six feet seam but was stopped by a fall so he came back to the East York Level where he found some men from the East side who had not been affected by the explosion. The overman informed him that he had withdrawn all the men from the East side workings. Shaw said:

I told him to keep them where they were and to bring them within 100 yards of the pit, and that as soon as I had the York Pit right for travelling in I would send for the men and let them up.

The ventilation was now short-circuiting and there was a strong current passing from the intake to the return through the West side crosscut. the shaft was cleared, all the injured men taken collected and taken to the cage and from there to the surface. The East side also sent men up in the cage, 28 at a time.

There was only one who survived the explosion, W.H. Lasbury, an assistant timberman. He went down the York shaft on the morning of the explosion at about 7.50 a.m. and went to the West York by the return. He then went to the about 20 to 30 yards below the engine on the York West incline when he heard a dull report. He was enveloped in a cloud of dust, which travelled from behind him and he lost his light. He fell forwards and he called to the engineman asking if he was all right to which he replied that he was. He turned back to the pit and groped his way out. As he neared the cross cut he heard a “sound as of air rushing through the doors in its ordinary way.” as he drew near “the doors crashed open and i hear a splintering sound” and he staggered back just on the inbye side of the doors, collected himself and staggered to the bottom of the York shaft where he dropped. This gave an indication that there had been two explosions.

Meanwhile, Shaw had gone to the surface with his party to get further assistance. He had been down the pit for an hour before work started to repair the water pipes in the shaft with which to fight the fires in the West Main Level. The fire in the East side crosscut was controlled by breaking a pipe on the East side leading from the column in the upcast shaft although it was damaged. The column in the downcast was completely cut off. Shaw started work within the hour to connect the pipes in the downcast shaft and bring water through the first cross-cut to the West side but he was greatly hindered with the fumes and smoke which affected his eyes very badly. there were many problems with the work and it took quite a time. It was not until the Porth Rescue Station arrived with breathing apparatus that a proper connection was made at . There was a mix up with the message that called them out and much valuable time had been lost. There was a trained Rescue brigade at the colliery but there was no breathing apparatus kept at the colliery.

The Commissioner commented:

In my opinion, the efficiency of the water supply was a most regrettable incident. Of course there is always the risk of broken pipes in shafts or underground being broken by the force of on explosion, but the time lost in repairing them would be much less than that absorbed by having to install a complete column.

When Dr. Atkinson and Mr. Redmayne arrived at the colliery on Tuesday afternoon at 5.30 p.m. the fires were being fought by water and fire extinguishers. There was no actual fire visible. It was buried under falls and it was arranged to fill and remove as much of the burning debris as possible with the object of advancing against the fire. Shifts were arranged to carry out the work. Each shift lasting six hours and acting under the direction of a colliery official or mining engineer.

The speed of the fan was slackened on the day of the explosion an a committee of mining engineers and others were appointed on Wednesday midday to control the rescue operations. It was suggested that sand would do the job but this was overruled as unnecessary. It was not until October, 17th. that sandbags were procured from Cardiff. At the Inquiry Mr. T. Greenland Davis, Junior Inspector of Mines was questioned about this point by Clement Edwards. He was asked:

I think you were present at an earlier stage when the Chief Inspector considered the question of using sand, and Mr. Leonard Llewellyn said it was not a sandy district, and I said if it were a question of sand I could get a hundred volunteers, get the railway company to run a train, and we would have sand within a few hours from Penarth and Mr. Llewellyn said they would have the fire out before they could get back.

It was not until stoppings were constructed to control the fire, problems with gas had been overcome and the ventilation restored that the exploration of the workings was undertaken. It was not until 10 p.m. on Tuesday night that an attempt was made to enter the Bottanic District. When the Inspector arrived at the at 5.30 p.m. on Tuesday he was informed that the air current on the East side was short-circuiting near the pit bottom. it was realised that gas could come from that side of the pit and get to the fire and it was arranged that the West side should be carefully watched and the roads leading to the West side examined. Messrs. T.G. Davies and P.T. Jenkins, Inspectors of Mines and two others did this about 9 p.m. which resulted in the discovery that the air, instead of coming from the No.1 North was passing into the Bottanic from the East side. With this knowledge, an exploring party was sent into the Bottanic District at 10 p.m. It was 11.30 when the first man was discovered alive but unconscious. By the early hours of Wednesday morning 18 men had been rescued alive. Work continued until all the bodies were recovered from the mine.

The official report into the disaster refrains from listing the victims by name and gives only a number, job and the cause of death. Four hundred and twenty-one were identified and eight were not. The larger number included seven who were brought from the pit alive and later died at home or in hospital. Eleven bodies were left in the mine buried under falls which brought the total death toll to 440.

Those who died were:

The single men:

| W.T.Attewell. | Humphrey Hughes. | Charles Peters. |

| G.D. Anthony. | George Herritts. | Ernest Petherick. |

| Thomas H. Abraham. | Brindley Hyatt. | Benjamin Priest. |

| Thomas Adams. | Reuben T. Hughes. | Hugh Parry. |

| Henry Brookes. | William Hughes. | Henry Pritchard. |

| Griffith Bowen. | Frank Hollister. | Frank Pritchard. |

| Samuel Booth. | Walter Henley. | Thomas V. Priest. |

| I.H. Benjamin. | Reginald Harrison. | W.J. Phillips. |

| Harold Button. | D.H. Hill. | William Robson. |

| Walter Berry. | Charles Hall. | Oliver Rees. |

| George Bastyn. | George Hallett. | Thomas Richards. |

| Charles Baker. | William Ingram. | Idris Price. |

| William Bennett. | Henry Jones. | Robert Ross. |

| Robert Bateman. | Gilbert Jones. | Evan Rowlands. |

| William Barnett. | Reuben Jones. | Taliesen Roberts. |

| Timothy Carroll. | Thomas Jones. | Griffith Roberts. |

| John F. Carnell. | Thomas D. Jones. | Thomas Rees. |

| George W. Coombes. | Thomas Jones. | I.J. Rosser. |

| Thomas Cotterell. | David Jones. | John Small. |

| Thomas Cook. | Samuel Jones. | Thomas Stanley. |

| John Carpenter. | W.J. Jones. | Thomas Saunders. |

| James H. Delbridge. | Hugh Jones. | John Symes. |

| William Davies. | Thomas Jones. | David Rees. |

| Thomas Davies. | David Jenkins. | John Rowlands. |

| D.J. Davies. | E.A. Jones. | Griffith Roberts. |

| Henry Francis Davies, widower. | Richard H. Jones. | Fred Richards. |

| Benjamin Davies. | William Jones. | Samuel Rowlands. |

| John Davies. | R.O. Jones. | Robert Rowlands. |

| R.J. Davies. | Samuel Jones. | William J. Ross. |

| James Davies. | William Jenkins. | E.G. Thorne. |

| Stanley Dando. | Henry Kearle. | Hugh Thomas. |

| George Downes. | Thomas Kestell. | E.R. Thomas. |

| Thomas Downes. | John Kenvin. | Thomas Tucker. |

| James Druhan. | Thomas Kinsey. | Thomas Thomas. |

| Richard Davies. | Rowland Lewis. | Thomas P. Thomas. |

| Mathew Dorey. | Griffith Lewis. | Albert Thorne. |

| Morgan Edwards. | C.W. Lewis. | James Twining. |

| W.D. Evans. | Phillip Lower. | E.S. Twining |

| D.R. Evans. | Frank Langmead. | Levi Thomas. |

| George Edwards. | Sidney Lasbury. | William Thomas. |

| Henry Edwards. | William Morgan. | Rees Thomas. |

| Evan D. Evans. | Josiah Morgan. | Joseph Thomas. |

| William Eldridge. | Benjamin Morgan. | William C. Thomas. |

| Walter Edwards. | Alfred Milton. | William Uphill. |

| J.R. Edwards. | Charles Moss. | Arthur Vranch. |

| William J. Edwards. | W.H. Morgan. | Ernest Vranch. |

| Rhys J. Evans. | John Maldoon. | William Williams. |

| Charles Edwards. | Albert McDonald. | W.O. Williams. |

| James Etchells. | Edwin Morris. | Arthur H. Williams. |

| Fred Ford. | Cadwalader Morris. | Albert Williams. |

| George Fred. | Thomas Maddocks. | John Williams. |

| Joseph Hopkins, widower. | Ernest Morgan. | William Taylor. |

| Fred French. | Meyrick Morris. | Emrys H. Williams. |

| Edward Gilbert. | E.E. Mulcock. | Glynder Williams. |

| Edward Griffiths. | David Morgan. | W.L. Wood. |

| William Richard Fern. | Thomas Mendus. | Noah Williams. |

| Albert J. Griffiths. | William Morgan. | Richard Williams. |

| Samuel Hoare. | Charles Owen. | Fred Williams. |

| Idris Humphries. | George Owen. | Henry Walsh. |

| William Hughes. | J.G. Owen. | Job Williams. |

| William Henry. | Harold Price. | Thomas Oliver. |

Those with other commitments:

Charles Brown who had two illegitimate children

Albert Button who supported his old mother

George Davies who supported his old mother with his brother

John Davies who supported his old mother with his brother

George Davies who supported his old mother with his brother

Ellis Davies who supported his old mother with his brother

David J. Davies who supported his aged mother

William Davies who supported his old mother

William F. Davies who supported his old mother with his brother

Thomas J. Davies who supported an aged mother

Ernest Edwards who supported his old mother

Alfred Evans who supported his old mother

Thomas Fern who supported his old mother

Arthur Gregory who supported his old mother

Alfred Hadley who had two illegitimate children

Hugh Hughes who supported his old mother

Benjamin Jones who supported his old mother

William Jones who supported his old mother

Thomas J. Jones who supported his old mother

Drychan Jones who supported his old mother

Thomas Jenkins who supported his old mother with his brother

Daniel John who supported his old mother

Richard James who supported his old mother

W.S. Jones who supported an illegitimate child

John R. Kirkham who supported his old mother

James Lower who supported his old mother

T.J. Morris who supported his old mother with his brother

Alfred Martin who supported his mother

William Morgan who supported his old mother

John Jones who supported his old father

Frank Ferris, a widower

John Twining who supported his mother and a niece

S.J. Mansfield who supported his old mother

Garfield Roberts who supported his old mother

Patrick Sullivan who supported his old mother

Arthur M. Richards who supported his old mother

Alfred R. Tudor who supported his old mother

W.H. Watkins who supported his old mother

A. Williams who supported his old mother

John Edwards who supported his mother and father who were both in their 80Õs

Frederick Alderman who left a wife and two children

Charles F. Anderson who left a wife and six children

William Baish who left a wife

George Baker who left a wife and nine children

Henry Boswell who left a wife and seven children

James Beavan who left an adopted child

John L. Benyon who left a wife and two children

Samuel Bird who left a wife

Edwin Bullock who left a wife and three children

William Bishop who left a wife

Samuel Baker who left a wife and two children

William Beck who left a wife and child

Frank Borinetti who left a wife who was pregnant

Denis Carroll who left a wife who was pregnant and a child

George Chant who left a wife and three children

Frank Clarke who left a wife and two children

Peter Carr who left a wife and child

Thomas Collier who left a wife and three children

John Chapman who left a wife and two children

James Colley who left a wife and two illegitimate children

Henry Copeland who left a wife and five children

Charles Chard who left a wife and four children

Thomas Cronin who left a wife and child

William Davies who left a wife and four children

Jeffrey Davies who left a wife and four children

Thomas Deers who left a wife and four children

Henry F. Davies who left a wife who remarried in March 1914 and two children

Albert E. Dean who left a wife and four children

James Davies who left a wife and three children

George Henry Downes married with one child

John Dillon who left a pregnant wife and a child

William Dew who left a wife and two children

Henry Davies who left a wife and three children

Henry William Dodge who left a wife and child

Morgan Evans who left a widow

Charles Evans who left a wife and four children

William Evans who left a wife and four children

David Evans who left a wife and two children

Thomas W. Edwards who left a pregnant wife

Richard Edwards who left a wife and two children

George Edwards who let wife and three children

James Edwards who left a wife and two children and who supported his old mother

Charles Emery who left a wife

R.J. Evans who left a widow

James Edwards who left a wife and two children

Evans Edwards who left a widow

Evan Evans who left a wife and child

George Henry Evans who left a wife and child

Robert W. Evans who left a wife and four children

William Evans who left a wife and six children

Henry Edwards who left a wife and five children

Henry Field who left a wife and three children

Henry Ford who left a wife and four children

Gomer Green who left a pregnant wife and a child

Llewellyn .i, who left a wife and three children

Edward who left a widow

James Gwynne who left a widow and four children

Walther Grainger who left a wife and child

David Griffiths who left a pregnant wife and two children

John Howlett who left a wife and five children

David Hughes who left a wife and five children

King Samuel Humphries who left a pregnant wife and five children

Frank Humphries who left a wife and a child

John P. Humphries who left a wife and child

James Herrin who left a pregnant wife and a child

William Harvey who left a wife and child

Richard Hunt who left a wife and five children, one of whom died 8th. November, 1913

Harry Hall who left a wife and child

William Hemmings who left a wife and three children

John Hughes a widower who left two children

William J. Hyatt who left a wife and six children

Thomas Hearne who left a wife and three children

John Herrin who left a wife and four children

William Hilbourne who left a wife and two children

George Harrison who left a wife and four children

Charles F. Hill who left a wife and two children

Edward Jones who left a wife and six children

John Jones who left a widow. and a child

Evan Jones who left a widow

Thomas H. Jenkins who left a wife and two children

Humphrey Jones who left a wife and child

Richard Jones who left a widow

Evan Jones who left a widow

William Jones who left a wife and three children

Thomas Llewellyn Jones who left a pregnant wife and five children

Evan William Jones who left a pregnant wife and a child

John B. Jones who left a pregnant wife and three children

Evan Jones who left a pregnant wife and six children

William Jones who left a wife and seven children

David J. James who left a wife and three children

Evan P. Jones who left a widow and two children

David Jones who left a wife and three children one of who died 23rd. January, 1914

Owen M. John who left a wife and child

Morgan Jones who left a wife who remarried, 4th. July, 1914

John H. Jones who left a pregnant wife and a child

Edmund Jones who left a wife and two children

James Jones who left a wife and eight children the youngest died 4th. November, 1908.

Henry Jones who left a wife who remarried, 10th. June 1914 and two children.

Thomas Jones who left a wife and seven children

Richard Jones who left a wife and child

Charles James Jones who left a widow

Christopher Jones who left a pregnant wife and a child

William Jones who left a widow

W.H. Jones who left a wife and two children

David Jones who left a wife and a child

William Samuel Jones who left a widow

William John who left a wife and two children

Daniel Kenvin who left a pregnant wife and three children

William King who left a pregnant wife and two children.

Richard Kestell who left a wife and child, John G. Kelly who left a pregnant wife.

Edward R. Lewis who left a widow.

Rowland Lewis who left a wife and two children.

Daniel Lewis who left a wife and two children.

John Lynch who left a wife and two children.

Thomas Lewis who left a widow.

Rowland Lewis who left a widow.

E.S. Llewellyn who left a pregnant wife and a child.

Silas Lock who left a wife and child.

John Lewis who left a wife and three children.

David John Lewis who left a wife and three children.

John T. Lewis who left a pregnant wife and five children.

Edward Lewis who left a wife and five children.

Edward Lewis who left a widow.

Ivor Thomas Lewis who left a pregnant wife and seven children.

Richard Mathews who left a wife and a child.

Robert Manning who left a wife and two children.

John Morgan who left a wife and two children.

Thomas Meredith who left a wife and two children.

James Moran who left a pregnant wife and child.

William T.Morgan who left a wife and five children.

John Maddocks, widower who left a daughter.

John Morris widower who left a son.

Benjamin Morris who left a wife and three children.

Frank Lewis Morgan who left a wife and five children.

Joseph Morgan who left a pregnant wife and one child.

Lewis Musty who left a wife and child.

David Lewis Morgan who left a wife and three children.

John Mogridge who left a wife and child.

Richard Newell who left a wife.

George Pingree who left a wife and child.

Albert Pritchard who left a pregnant wife and five children.

Thomas Phillips who left a wife and two children.

William Payne who left a widow.

John Peters who left a widow.

George A. Price who left a wife and two children.

Charles Parry who left a widow.

Benjamin Priest who left a wife and four children.

Albert Pegler who left a pregnant wife and four children.

Albert Parrish who left a pregnant widow.

Henry Penny who left a wife and child.

W.J Rees who left a pregnant widow.

David T. Richards who left a wife and three children.

Gwilym Rees who left a pregnant wife and two children.

T.W. Roberts who left a wife and child.

John Radcliffe who left a widow.

John Roberts who left a pregnant wife and two children.

William Rowlands who left a widow.

William Ross who left a wife and two children.

Richard Rees who left a wife and three children.

Morgan Roberts who left a wife and child, Richard Rex who left a wife and child.

Robert Rock who left a widow.

John Richards who left a wife and three children.

John Robinson who left a wife and two children.

Richard Rees who left a widow.

Lewis Rees who left a widow.

Peter Ross who left a wife and child.

Edward Rowlands who left a pregnant wife and six children.

George E. Sreadbury who left a wife and three children.

Samuel Edwin Small who left six children.

James Smith who left a wife and three children.

James Scrivens who left a wife and three children.

John Scott who left a pregnant widow.

Edward Stephens who left a wife and four children.

Edward Stanton who left a pregnant wife and a child.

Richard Seagar who left a pregnant wife,

William Sullivan who left a wife and four children,

George Small who left a wife and child.

Ezra Twining who left a wife and two children.

David Thomas who left a wife and five children.

Rees Thomas who left a wife and child.

Thomas Thomas who left a wife and two children.

John Thomas who left a wife and three children.

William Thomas who left a wife and two children.

James Thomas who left a wife and seven children.

Henry Thomas who left a widow.

Isaac Taylor who left a widow.

Richard Thomas who left a wife.

Frank Tooze who left a wife and three children.

Howell Thomas who left a pregnant wife and four children.

Llewellyn Williams who left a pregnant widow

Joseph Williams who left a wife and two children.

David Williams who left a widow.

Caleb Withers who left a widow.

John Williams who left a wife and two children.

Fred Williams who left a wife and three children.

Evan Weston who left a wife and child.

Simeon Woram who left a widow.

Gilbert Whitcombe who left a wife and two children.

William H. White who left a pregnant wife and two children.

John White who left a wife and two children.

David Williams who left a widow who supported his old mother.

W.H. Williams widower who left three children.

Fred Williams who left a wife and two children.

Joseph Wright who left a wife and two children.

Patrick Williams who left a wife and two children.

Frank William Waddon who left a wife and child.

John Witherall who left a wife and child, Gwilym Williams who left a widow.

Robert Yardley who left a wife and four children.

Thomas Hopkins who left a wife.

David John who left a wife and four children.

David Jones who left a wife and six children.

Henry Mainwaring who left a wife and two children.

Daniel Price who left a wife and

William Price who left a wife and three children.

On the 16th October, a rescue worker, William John, aged 31, lost his life as he was standing at the top of a fall handing timber forward when a stone fell fracturing his skull and he was killed.

A fund to relive the suffering of the victims dependants was set up and captured the imagination of the public. The above list is taken from the document that details the payments to the people who had lost their breadwinners.

The inquest into the deaths of the men was held at Senghenydd on Monday 5th. January, 1914 before Coroner David Rees. the proceedings lasted seven days with the jury bringing in a verdict of “Accidental Death.”

The inquiry into the causes and circumstances attending the explosion at the Universal Colliery was conducted by Mr. R.A.S. Redmayne, Chief Inspector of Mines. All interested parties were represented and the proceedings lasted almost a month. Two very large volumes of evidence resulted. The investigation was painstaking with Edward Shaw being examined for three whole days and some witnesses recalled again and again.

Mr. Redmayne wrote of the probable site of origin of the explosion and its probable cause:

I have come to the conclusion that the is a strong probability of the explosion having originated in the Mafeking Incline and that it was preceded by a similar occurrence to that which took place further outbye of the Mafeking return in October, 1910, namely, by heavy falls liberating a large volume of gas.

These heavy falls exposed seams of coal and beds of hard rock, and an outburst of gas may have come away at one of them. the only apparent means of ignition would be sparks from the electrical signalling apparatus, or from rocks brought down by the fall, and we know that explosions have been by both causes.

The only other possible means of ignition were safety lamps or matches. The difficulty in regard to the former is that no lamp was found in the place, and even were a broken lamp found under a fall there would be the inference that it had been broken by the fall. There were, however, lamps lower down the hard heading, but there is no evidence pointing to any of them having been the igniting cause of the explosion. In respect of matches, a rigorous search of the persons descending the mine was carried out daily, and the possibility of a match being the igniting cause is, in my opinion, remote.

Exhaustive test had been carried out on the electrical signalling apparatus. The General Regulations gave precautions which should be taken to avoid “open sparking” from electrical and wires in mines in which there was inflammable gas. Mr. Redmayne wrote:

Undoubtedly electrical signalling wire was being used in a part of the mine in which there was likely to be inflammable gas in quantity sufficient to be indicative of danger.

it was argued by the counsel appearing on behalf of the owners and management, and evidence was called to show, that the sparks caused by bringing the wires together, or in ringing the bells, were not of sufficient intensity to ignite the gas. In effect there was no “open sparking”. In this connection, I can only regret that the safer plan of excluding sparks altogether was not adopted.

It is all the more astonishing that the management should have faced the risk that sparks might have ignited gas in view of the Bedwas Colliery explosion which occurred on March 27th., 1912, and was proved beyond all reasonable doubt to have been caused by the sparks from an electric ball. The attention of owners of mines throughout South Wales was called to this explosion in a circular letter sent out by Dr. Atkinson, dated 28th. August 1912.

With reference to the rescue apparatus at the mine, Mr. Redmayne added some recommendations:

I incline to the belief that if there had been rescue apparatus kept at the colliery, and men equipped with breathing apparatus and carrying with them a lighter form of apparatus, had at once penetrated the West York by the Return and the Bottanic District a few more lives would have been saved.

I am convinced that had there been available at the time an adequate water supply, and had the brigades of rescuers attacked the three fires, the fires might have been extinguished in a comparatively short time.

I should have thought, in view of the fact that the colliery was such a gassy one, and as it had already been devastated by an explosion, that the management would have made arrangements for a supply of water adequate to meet an emergency of that kind that had actually occurred.

With regard to the state of the mine prior to the explosion the Commissioner pointed out that it was breach of the Act not to have cleared coal dust from the roof and sides and he commented on the desirability of stone dusting.

I know that apprehension exists in some quarters as to whether such a remedy would not be worse than the disease, the idea being that the introduction of stone dusting might be conducive to “miners’ phthisis” (pneumonokoniosis), bit I would point tote fact that dust derived from argillaceous shale has existed naturally in mines in the United Kingdom for long past without, as far as I know, injurious effects resulting to the workmen employed therein.

The Report drew attention to the fact that there had been several breaches of the Coal Mines act and in a general comment about the management of the mine. M.r Redmayne said:

Several oft these breaches, may appear trivial, but taken in the aggregate they point to a disquieting laxity in the management of the mine.

I regret exceedingly having to say this because Mr. Shaw impressed me as an honest, industrious and in many respects, an active manager and he gave me his evidence in a clear and straightforward manner and assisted the Inquiry to the utmost of his power.

Abut the manager’s behaviour on the day of the disaster he commented:

It would be invidious, where all the mining engineers and miners engaged in attempted rescue operations worked so hard in endeavouring to get past the fire in the workings with the object of saving life, to commend individuals by name, but I think a particular meed of praise is due to Mr. Shaw and to the small band of workers which accompanied him underground immediately after the explosion.

REFERENCES

Reports to the Right Honourable The Secretary of State for the Home Department of the causes and circumstances attending the explosion which occurred at the Senghenydd Colliery on Tuesday, 14th. October 1913 by R.A.S. Redmayne, C.B., H.M. Chief Inspector of Mines (Commissioner) and Evan William Chairman of the South Wales and Monmouthshire Coalowner’s Association and Robert Smillie President of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (Assessors).

Colliery Guardian, 17th. October 1913, p.798, 21st. November, p.1049, 9th. January 1914, p.89, 16th. January, p.143, 13th. February, p.352, 1st. May, p.949, 961, 24th. April, p.900, 8th. May, p.1011.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

Return to previous page