WELLSWAY Midsomer Norton, Somerset. 5th November 1839

These men and boys were hooked to the top and when their weight was felt fully on the rope it broke asunder precipitating the twelve to the bottom of the pit, some 756 feet. Only one body was sufficiently whole to be recognised. The rest were smashed and dissevered, limb from limb. The unthinkable was suspected for the rope nearly new after six months of being worked with 37 hundredweight had the appearance of being cut with a knife or chisel passed over the fibres. Despite an astute newspaper reporter’s discovery that the previous night, sixteen had been brought up when usually only ten were allowed, and this meant that the dead shift had been overmanned by two, the rumour was allowed to persist.

George Kingston, the bailiff told an inquest the rope had seemed perfectly secure. He was at the pit when the accident occurred. All of a sudden the rope broke and the end came with a great crash on the shed where he and others were standing. The rope was made ready again and three men went down as soon as possible. He thought somebody must have injured the rope to make it break. He left the pit the night before at a quarter past eight and had seen nothing untoward. He slept at the works and heard no noise in the night. He knew of no ill-feeling between the men. (You can almost hear the sadness and bewilderment in his voice at what was being covertly suggested). He had always believed them to be on a friendly footing.

Thomas James was in the pit at 4 o’clock in the morning. The twelve were about to descend. Just as he pulled back the runner he heard Will Summers say. “How the rope jumps,” and with that they all fell to the bottom. The rope must have been tampered with. John Fricker confirmed the statements of Kingston and James.

Thomas Hill described how he had descended with two others and found the bodies, in a scene resembling an abattoir. “It presented a mass of steaming human gore”, he said. The rope had been cut by a person or persons unknown was the verdict, though there does not seem to have been any hue and cry raised to search for the alleged culprit. In all probability there was no culprit, but the merest suspicion that one existed would prevent any prosecution for manslaughter due to negligence.

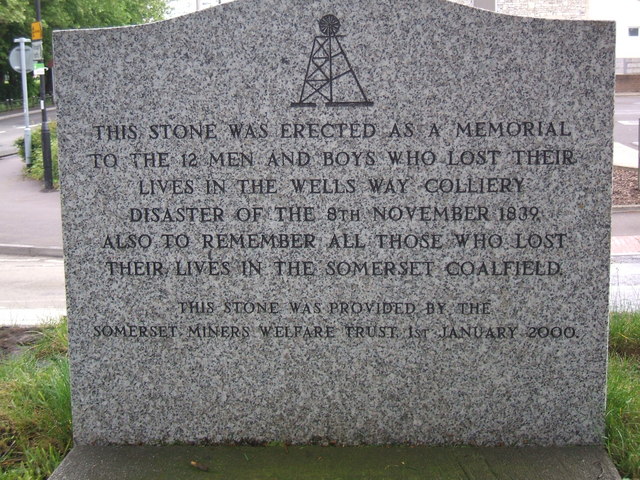

Miners Memorial, Midsomer Norton

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Nigel Shoosmith – geograph.org.uk/p/432526

Those who died were:

- James Keevill aged 41,

- Mark Keevill aged 13,

- James Keevill, Jun, aged 13,

- Richard Langford aged 45,

- Farnham Langford aged 15,

- Alfred Langford aged 13,

- James Pearce aged 17,

- William Summers aged 24,

- William Adams aged 20,

- Leonard Hooper Dowling aged 13,

- Amos Dando aged 12,

- John Barnett aged 41,

Killed in the Wellsway Pit disaster of 1839. Thus saith the Lord, set thine house in order for thou shalt die and not live – so reads the inscription on their mass grave in Midsomer Norton churchyard.

Four thousand people attended the funeral. The rain descended in torrents from the sky, its dark and murky character appeared to sympathise with the heartrending grief and agony of the deceased’s relatives.

The Wellsway proprietors supplied the coffins, each having a velvet pall. The vicar of Midsomer Norton gave the ground free. Funeral knells were rung in Kilmersdon and Radstock as well as Midsomer Norton. Mr C. Ashman, the works manager, led the procession and a clerk and bailiff preceded each coffin which was carried by four and supported by six miners one hundred and twenty pallbearers in all. Major Savage, Captain Dickson, Messrs V.G. James, Eustace Scobell, B. Smith, J. Hill, S. Palmer, Biggs J. Smith and T. Hollway, neighbourhood proprietors, joined the mourners as they entered the church. The Keevills and the Langfords, along with their mates were buried in one grave.

A stone was erected in the churchyard at the expense of the masters of the Wellsway Coalworks. The inscription reads:

In this grave are deposited the remains of the twelve under mentioned sufferers all of whom were killed at Wellsway Coal Works on the 5th November 1839, by the snapping of the rope as they were on the point of descending into the pit. The rope was generally thought to have been maliciously cut.

The original stone was renewed by the Somerset Miners in 1965.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

Return to previous page