The election of a Conservative Government under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 brought about a hardening of attitudes within the National Coal Board (NCB) with regards to the profitability of collieries. In 1980 the South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) carry out a four-day strike against pit closures which was bought off by false promises. The Lewis Merthyr/Ty Mawr Colliery near Pontypridd was closed in 1981 but the South Wales miners failed to galvanise the support of the other miners to strike, and this perhaps persuaded Thatcher to plan ahead and break the power of the National Union of Mineworkers.

Most of the collieries in Caerphilly, and in the South Wales Coalfield, were starved of investment until by the beginning of 1984 the losses per tonne of the collieries of the County were:

- Bedwas Navigation £21.20

- Celynen North £24.20

- Celynen South £59.50

- Markham’s Navigation £3.90

- Oakdale Navigation £7.50.

Only Penallta Colliery was making a profit at £0.90p per tonne of coal produced. In 1982 investment into the industry to construct new capacity and facilitate improved coal treatment came to £453 million in North Yorkshire alone, even the smallish Western Division received £75.7 million while poor old South Wales received only £7.63 million.

In March 1983, the NUM held a national ballot on whether to take strike action over pit closures, 68% of the South Wales membership voted for strike action, but overall in the UK’s pits, only 39% voted that way and a national strike was abandoned. This was the vote that was later to cause a lot of confusion and bitterness at the start of the big strike.

At a national level the Conservative Government were preparing for a showdown with the NUM which had always been viewed as the vanguard of the trades union movement, break them and the road to capitalist market economics would be wide and open. Draconian labour laws were introduced, that included a limitation on picketing numbers, banning secondary picketing, sequestration of union funds, social security laws were altered to prevent payments to strikers, coal stocks were built up to an all-time high, police tactics and cooperation between forces was enhanced as well as police pay, and so on.

The Rhymney District of the South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers in 1984:

- Executive Council Members: B. Hamer, G. Woolf.

- Lodge Secretary Compensation Secretary

- Bargoed Surface C. Cook

- Bedwas C. Harris G. Davies

- Britannia K. Edwards

- Markham R. Gurmin B. Mantle

- Oakdale A. Baker C. Tapper

- Penallta B. Elliot

- Tredegar Combine J. Heath A.G. Richards

In March of 1984, the National Coal Board announced the closure of pits in Scotland and Yorkshire, immediately the Yorkshire miners came out on strike or was picketed out.

When the big strike came, it came as a surprise for the miners of the South Wales Coalfield. The leadership of the South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers called a Delegate Conference at Porthcawl to discuss the situation. Most of the delegates attending that conference believed that it had been called to discuss a ballot on strike action, but it had not – the National leadership of the Union had decided that they would probably lose a ballot on strike action so recommended that areas use a little known rule (Rule 43) that allowed them to take individual action by conference vote. The executive council’s recommendation was overwhelmingly carried with only five lodge’s voting against it.

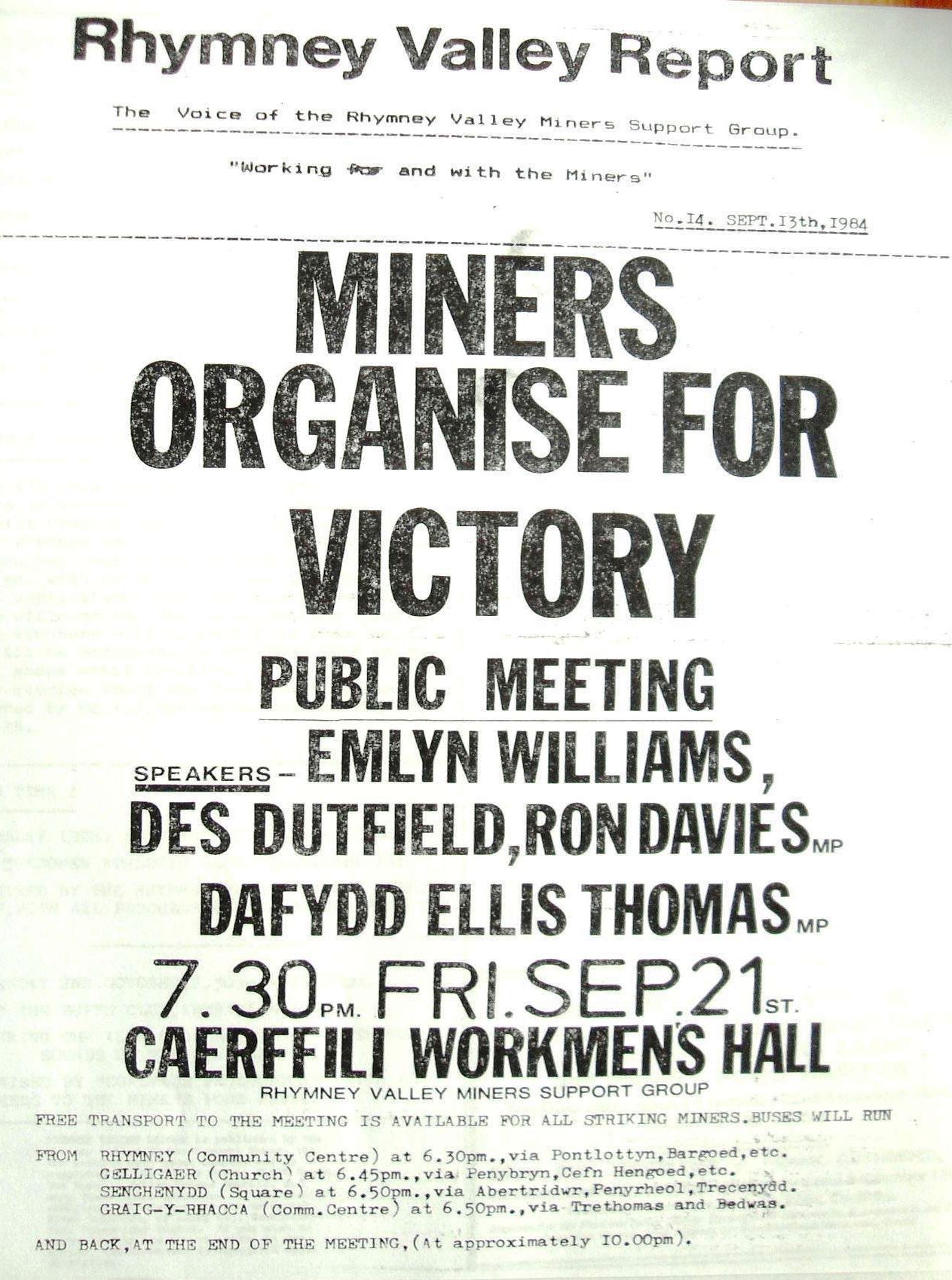

The representatives of 46 lodges consisting of 21,500 men gathered in the hall and heard Emlyn Williams the Area President report that a few hours earlier the Area Executive Council had considered the situation in the other coalfields, had deliberated on Ian Macgregor’s statement on pit closures, had listened to the President’s report of the National Executive Committee’s recommendations, and decided to support the NEC’s resolution to permit areas to take individual strike action under Rule 43, and furthermore to recommend to this conference that there will be no work in South Wales from Monday 12th of March 1984. This took a moment to sink in with the first lodges to the rostrum generally expressing concern over the lack of consultation with their members. Penallta, Bedwas, Blaenserchan, Garw and the Celynen South give this view, with the Celynen South also expressing concern over the timing of the strike, stating that the overtime ban (which was in its eighteenth week) should continue until the winter and then national strike action should be taken. Then George Rees, Area General Secretary, and executive council members rallied support and most lodges who spoke then supported immediate action, these included Celynen North, Tower, St. Johns, Lady Windsor, Mardy, Blaenserchan, Taff Merthyr, Cwm, Oakdale, Betws, Nantgarw, Merthyr Vale, Markham, Bargoed, Penrhiwceiber and Treforgan, and when the vote was taken only five lodges voted against the resolution.

The South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers was out on strike action without consulting its members but in accordance with its Rule 43 and the mandate given by the 68% pro strike vote in 1983.

Nottingham and other productive areas of the English Midlands did not join the strike call.

Nottingham and other productive areas of the English Midlands did not join the strike call.

Despite the president’s ruling against lodge’s voting on this issue, many did at general meetings held throughout the Coalfield during that week-end with thirty-five of them deciding to work as normal on Monday, many men were angry over there being no ballot, and others were angry that the other area’s had not supported the South Wales miners when they took action over the closure of Lewis Merthyr Colliery. There is no doubt in my mind that if a ballot of the South Wales miners had been taken over that weekend the majority would have voted against strike action.

By the Sunday evening, it was reported by the media that only 11 of the 46 South Wales Lodges had voted for strike action at their general meetings. Even in the other areas of the South Wales Coalfield, the area executive council members were not having it their own way, in the Maesteg and Swansea Districts, three out of the five executive council members failed to carry their own lodges.

On the Sunday morning some of the most militant lodges of the Coalfield; Tower, Mardy, Trelewis, Treforgan and Aberpergwm met in the ambulance hall at Hirwaun and devised a strategy to bring all of the Coalfield out by picketing those who had decided to work. They started by picketing the area executive council meeting on the next day, demanding that they stand firm. This they did and issued the following decrees;

- That the miner’s agents arrange mass committee meetings in their areas the following morning.

- That a strike committee is formed from the executive committee.

- To stand by the conference decision and issue the following press release;

The South Wales area executive council having received an updated report of the situation in the coalfield this morning, unanimously decided to call on all our members to declare their unanimous support for those of our members who are carrying out conference decisions.

We thank all our members who have made this decision to stop the destruction of the South Wales Coalfield.

On the Monday and Tuesday, the above lodges, joined by others such as Lady Windsor and Penrhiwceiber picketed the lodges that turned up for work and within the next two days, by picketing, by persuasion, by group and colliery meetings all pits had joined the strike in some form or other.

Most of the Gwent and Rhymney Valley lodges were now of the opinion that a recall conference should take place, and in that conference, a call for a ballot should be made, but they hadn’t reckoned on the oratorical powers of George Rees the area general secretary. On that Thursday evening a meeting of all the lodge’s in the Gwent and Rhymney Valley Districts was called and George Rees made a rallying call to what was viewed as the weak link in the solidarity of the strike. The muted pleas for a ballot were drowned by the sheer personality of George Rees, he badgered, he bullied, he pleaded in a thirty minute speech, and that alone, kept the miners of Gwent from returning to work. The strike was now solid in South Wales and the men with their stubbornness against adversity which had been passed on through the generations, and engendered by the nature of their work, settled down for a long hard slog, many knew that they could not win but pride would not let them surrender without one hell of a fight.

On the other side, the Government had prepared the ground well, had chosen the time for the confrontation and appeared determined to destroy the NUM forever as part of their wider strategy to emasculate the whole trades union movement, they had a leader in Margaret Thatcher who was as uncompromising as Arthur Scargill in her determination promote her dogma, who was presiding over rising unemployment and the creation of an underclass with a contemptuous disregard for all who were not of her ilk. She chose a ruthless Canadian millionaire, Ian Macgregor, as chairman of the National Coal Board, and brought in the most stringent anti-trades union legislation in western Europe. She gave the police forces pay rises way above pay rises given to other public sector workers and underwrote all police overtime due to the dispute. She was prepared to meet any financial cost to destroy the miners (some say the total cost came to over £4 billion), which was many times over more than the cost of any subsidy to keep loss-making pits open. She decisively won the propaganda war with most of the press supporting her and had a glut of coal and other power sources available for distribution. On top of all this, the self-centred miners in the highly productive pits of the English midlands were contemptuous of anything but their own pockets and without any notion of solidarity with those that needed help, the majority continued working.

By early April there was another setback to the strike when the steelworkers union agreed to ignore picketing miners and to use ‘blacked’ coal supplies. The Nottinghamshire NUM delegate conference voted by almost three to one not to go on strike. By the middle of the month of April, 122 pits were strikebound and only 43 were working normally.

Throughout the nice warn summer of 1984, the strike remained firm in South Wales, mass picketing of steelworks and other industrial sites and of the working pits in the English midlands continued with little success. The men and their families endured many hardships, mortgages and rents were in arrears, food was short and children relied on hand me down clothes or charity. The public response to these hardships was tremendous £750,000 was collected by the Gwent Food Fund alone, yet despite all the hardships, the men and women out on strike the vast majority of the men remained loyal to their union.

Picketing was organised from the central office of the union at Pontypridd and in the early days, it was estimated that 25% of the workforce (around 5,000 men), were active in picketing the local power stations and targets in England. By the end of March, South Wales were picketing pits in such places as, Lancashire, Nottingham, Warwicks, Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Leicester and North Wales. Power stations at, Wylfa, Didcot, Hinckley Point, Fawley and Tilbury were picketed, and collection points for funds at Birmingham, Swindon, Southampton, Worcester, Crewe, Devon and London were set up.

Yet there was still no movement for a settlement from either side, and some of the picketing points became scenes of violence as the police tactics employed ensured confrontations. At Orgreave in Yorkshire, on the 29th of May, a mass picket of 7,000 miners, many from south Wales was arranged to try and stop coke being moved to the local steelworks, mounted police charged the picketing miners causing many injuries and 84 arrests. Meirion John was at Orgeave with the Gwent pickets:

Orgreave was going to be the big battleground, and I think it was what the police wanted as well. When we had picketed places like Daw Mill Colliery in Warwickshire they would stop you miles away from the pit and you’d have to park up and walk. But we got right to Orgeave with no trouble. We were told exactly where to park in the small village and they let us decide which end of the picket line we were going. It was open police lines and you could walk either side of the plant. No problems, nothing at all. You could smell a rat as soon as you got there and, as the day went on, something obviously was.

At our end of the line there was a bit of banking, right in front of us there were four or five lines of police right across the breadth of the area, and behind them, there was a line of horses and in amongst them were the snatch squads, the ones with the short shields waiting to come through. On the right-hand side was a field with police on horses, and in the other field were police with dogs that looked like they hadn’t been fed for a while! It was totally organised by the police, it was like looking at a battlefield but one army was organised and the other one wasn’t.

At first, it was the usual pushing and shoving and everyone was having a laugh. But when we turned to the boys from Yorkshire and asked “How do you know when the lorries are coming?” they said “You’ll know because they’ll send the cavalry out” and that’s exactly what happened. There was stone-throwing on one side but that was after the charges. Everything that you saw on the telly was out of synchronisation, it didn’t happen like that because the stone-throwing was in defence of all those horses and snatch squads just picking up stragglers.

The police were three or four deep. The ones in front with the big shields had their truncheons out because they were banging their shields with them, but the ones behind were actually using their truncheons on us. They first locked shields to push you back and once you were in disarray they would come through. They would then send out the horses next to spread everyone and then the snatch squads with sticks and the small shields just picking everyone up…you could see all the snatch squads going wild with their truncheons…they were hitting men with no protection. They were just wild and over the top. They were going to smash the strike there and then…They were all kitted up and we were in trainers and jeans.”

In our own ‘patch’ at Margam and Llanwern steelworks, there were many arrests as the convoys of coke lorries travelled the M4 with their ‘blacked’ cargoes and entered Llanwern.

Along with the picketing another very important part of the strike was being carried out; the food funds and collections for them. There was no strike pay from the NUM, just £1 per day for picketing locally, and £2 for picketing nationally, and this would soon stop due to the enormous cost of the strike (something like £35,000 a week at the onset) and sequestration of the union’s funds. There were no social security benefits for strikers only small payments for children and non-working wives.

Along with the picketing another very important part of the strike was being carried out; the food funds and collections for them. There was no strike pay from the NUM, just £1 per day for picketing locally, and £2 for picketing nationally, and this would soon stop due to the enormous cost of the strike (something like £35,000 a week at the onset) and sequestration of the union’s funds. There were no social security benefits for strikers only small payments for children and non-working wives.

It appears that Oakdale lodge was the first to start collecting food (on April 13th) and the initiative grew into the huge Gwent Food Fund that was based at Six Bells. Without the efforts of the women, from all lodges, involved in the collection, sorting out, and distribution of the thousands of food parcels, and eventually all aspects of the strike, the consequences would have been dire indeed. Alongside the food parcels ‘soup kitchens’ were set up in many of the miners’ institutes, including the one at Newbridge for both of the Celynen lodges which provided hot meals for those in need. Collections ranged from local supermarkets to the major cities in the UK. They also came freely from other trades union members, both at home and abroad, and particularly the print unions. One anecdote was regularly repeated that one day a miner was collecting food outside a store at Blackwood with the tins that he been given in a wire basket, along came an old lady, took five tins of corn beef and gave him five pence, he didn’t like to stop her!

Help also came from the local authorities with no pressure on the payment of housing rents, and in the case of Blaenau Gwent, and the Rhymney Valley District Council, a food voucher to the value of £10 was given out. In one week £542 in cash and stacks of food was collected in the Cwmbran area. The good people of Bristol donated £2,000 in one week to give the children of Blaenserchan strikers a holiday.

Along with the food collections, peoples generosity branched out in other ways, the Caerphilly Constituency Labour Party took 80 Rhymney Valley children to Barry Island for the day. The Woodcraft Folk offered free holidays to children in Kent, and France was the location for some children.

The area NUM had refused to stop secondary picketing, particularly at Llanwern and Port Talbot, so on the First of August all bank accounts held by the various parts of the union in South Wales, including food funds, were confiscated, and the area fined £50,000 for not complying with the court order. This in reality was a body blow to the strike and it was the main cause in changing the direction of picketing from one of the outside of the Coalfield to concentrating on events nearer home. It also, in part, made the union realise that the mass picketing of steelworks and of working pits was not going to work.

The emphasis now turned from the ‘macho’ approach of mass picketing to a softer campaign of how suffering was evident in the Coalfield, and how this suffering would be continued after the strike if the jobs and communities disappeared, although mass picketing continued and some say it was necessary in the times ahead. Indeed it brought some spectacular publicity when Gwent miners hijacked the Transporter Bridge at Newport, and some disturbing scenes, at Dowd’s Wharf at Newport where a car blocking the entrance to the wharf, was set on fire.

Financial difficulties began to bite, mortgages remained unpaid, food was short and children relied on hand-me-downs for clothing. By September 1984 the Gwent Food Fund was in full flow, organised by miners and their wives and families it was one of the largest in the UK dealing with 5,000 food parcels each week, the average food parcel costing between £4 to£6. Up to that date the Fund had received £129,000 with only £23,000 of that coming from the Union, the rest had been collected from as far afield as Holland. At its close on the return to work, it had collected £750,000.

Collecting efforts and donations were not only confined to the UK. Just after Christmas the Austrian TUC invited 26 Gwent miners children to a skiing holiday in the Alps. The Blaenau-Gwent banner was even raised in the European Parliament at Strasbourg.

In the late autumn, a change came over the coalfields, the bloody-mindedness of the Government and the emasculated leadership of the NUM at the National level created an air of despondency, and a small but significant return to work began. The onus of picketing now began to change from the offensive to the defensive at South Wales pits.

By August 1984 the men were beginning to question the conduct of the strike and in the first week of November a few men returned to work at Cynheidre Colliery in west Wales which in itself was insignificant, but it did start a chain reaction throughout the Coalfield and through the coming month’s men returned to work in dribs and drabs and then in larger amounts at collieries such as Six Bells and Marine. The onus of picketing now changed to the defensive from the offensive and mass picketing was carried at the pits where a return to work occurred.

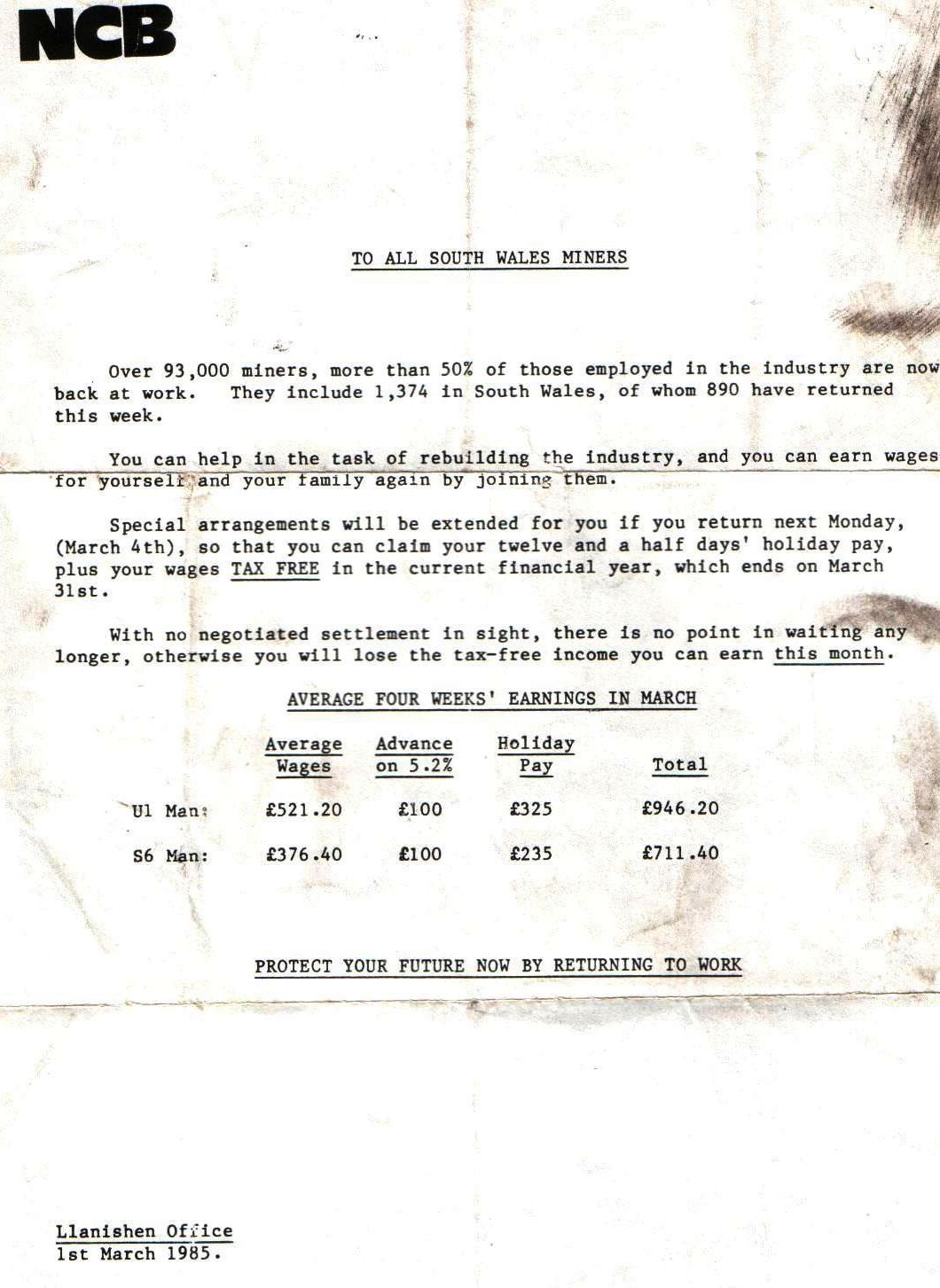

On Bonfire Day 1984, 802 miners returned to work nationally, but significantly for South Wales, fifteen men returned to work at Cynheidre Colliery near Llanelli and one at Nantgarw Colliery. These were the first men to return to work in the area after eight months on strike. The NUM responded by withdrawing all safety workers. In Yorkshire, 139 men were now working. In the third week of November, the NCB upped the pressure on the strikers by offering up to £175 ‘on account’ of the expected pay rise that was pending before the strike and an additional £1,200 to anyone who started back this week.

They also made the following guarantees:

- A guaranteed job for every mineworker who wants to stay in the industry, plus transfer benefits if his pit closes and generous allowances if he has to move home.

- No compulsory redundancies.

- The highest redundancy benefits in Europe for those who leave voluntarily.

- Pay increase of 5.2% backdated to November 1st 1983.

- Deep-mined capacity of at least 100 million tonnes a year as expanding sales result from low-cost coal.

- Continuing investment in mining at a high level.

They didn’t say for how long though, and all of these promises were betrayed.

One man started back at Markham, two at Roseheyworth and three at Six Bells. Scenes of confrontation between pickets and the police became commonplace at places such as Bedwas, Roseheyworth, Marine and Celynen North.

It was also around this time that the Celynen North and Marine Lodges were now supporting a call for a re-call conference to discuss the strike. Picketing now changed from the offensive to the defensive, with mass picketing at Bedwas Colliery in an attempt to stop men from returning to work. The leadership of the Marine Lodge was so concerned about the situation at their colliery that they wrote to the Area Union in November 1984 calling for a National Conference to re-negotiate an end to the dispute.

The battles with the police protecting the returning miners were now becoming particularly bitter, none more so than at Roseheyworth. The working miners were granted Legal Aid and their lawyers presented an injunction to the High Court at London pressing various claims. The sitting lasted ten days and ended on the 11th of February 1985, the claims against the National NUM were dismissed as were the claims against the South Wales Area of the NUM, but the claims against five South Wales NUM Lodges including Roseheyworth were granted and “Union Officials including Lodge Officers at that particular Lodge acting on behalf of the Union, must not incite, procure, assist, encourage or organise Union members or anyone else to congregate at or near the entrance to that particular colliery.” also at Roseheyworth ” must not picket or demonstrate at Crosskeys College for the purpose of persuading Mr. Sheehan not to work.”

In South Wales, 117 men were now working and the violent picketing associated with places such as Orgreave now came home, 500 hundred pickets tried to stop two men going to work at Merthyr Vale Colliery; in the melee, a police van was overturned.

The return to work in South Wales was still a tiny minority of men, but in the other coalfields, whole pits were returning at a time. Apart from now picketing their own pits, other picketing carried on. One of the most striking incidents occurred when the Gwent lodges ‘captured’ the transporter bridge in Newport.

Hopes were raised of a victory around Christmas time when the officials union, the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS) threatened to go on strike, their members voting overwhelmingly in a ballot for a strike, however, the Government were quick to resolve this dispute and the NUM continued alone.

The NACODS vote in South Wales was 1,287 for strike action and 145 against, while the national numbers were 11,660 votes for strike action and 2,470 against. Even 75% of the midland officials voted for strike action. Things were looking rough at Bedwas with an NCB report stating:

Deteriorating roof conditions exist for half the face length of the M46 face adjacent to the main gate. Many supports are fast and a considerable number are approaching this position. Floor lift in the supply road will need to be cut to get supplies to the face. Heavy floor lift is occurring in the new Big Vein district and the B102 face will not restart. There is restricted clearance in the loco haulage road and poor conditions in the South pit bottom due to flooding which has occurred on two occasions.

January turned to February and the strike dragged on, now without purpose and without hope of victory. Throughout the Coalfields men started to return to work in droves, except for South Wales where the return was minimal, South Wales scabs managed to obtain an injunction limiting picketing at the pits. A bloke by the name of Mr. Justice (a bit of a joke that) Scott granted an injunction to stop picketing at Cynheidre, Cwm, Roseheyworth, Merthyr Vale and Abernant. On the 12th of February four men returned to work at Oakdale Colliery prompting the removal of safety men by the local lodge. The NCB then, claiming that the pit would flood, toured the locality with loudspeakers asking men to return to work to man the pumps. None did but eventually, an arrangement was made with the lodge to save the pit.

It was also in February that again Marine NUM Lodge issued a warning to the Area – Alan Day their spokesman told an Area Conference “loyal trades’ union members were now about to go back to work, it would be extremely difficult to hold them.” At the Area Conference held on the First of March 1985, he was joined by S. Bartlett of Roseheyworth NUM Lodge and by Brian Inch of Six Bells NUM Lodge in calling for a return to work. By February of 1985 in south Wales over 95% of the men remained loyal to the union, but accepting the inevitable area conference of the South Wales Area of the NUM in March 1985 decided on a return to work.

At the National Delegate Conference held at the TUC centre on the following Sunday, March 3rd 1985, the South Wales delegates had a rough time from some diehards, but also gave the NUM national leadership a rough time in not taking decisive leadership to end the strike. As George Rees was later to quip, some of the English Coalfields were willing to carry on until the last drop of Welsh blood had been spilt.

The South Wales Miners returned to work with their heads held high and conscious that no other group in the World, past or present could have exhibited the character that they had shown. The return to work was not an acceptance of defeat by the Government but an attempt to save their inheritance; the South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers from extinction. Back to work we went, defeated and demoralised and to an uncertain future.

The old Area NCB Director P. Weekes, generally thought to have been sympathetic to the mining industry retired and hardliners were brought in throughout the management structure of the Area. Socio-economic matters were not their problem Pal, you produced or shut. Ironically in their haste to please their political masters, they eventually did them out of work.

Those at work at the end of February 1985 Nationally:

- Scotland 5,774 men at work 47.4% of the workforce

- North-east 20,895 men at work 49.5% of the workforce

- Yorkshire 10,647 men at work 21.0% of the workforce

- Western 12,337 men at work 87.0% of the workforce

- South Wales 1,471 men at work 7.5% of the workforce

- North Derbs 7,285 men at work 78.0% of the workforce

- South Midlands 9,614 men at work 81.4% of the workforce

- Nottinghamshire 25,800 men at work 95.6% of the workforce

Those at work in Gwent:

- Abertillery New Mine 151 men at work 37% of the workforce

- Six Bells 111 men at work 23% of the workforce

- Marine 118 men at work 19% of the workforce

- Celynen South 72 men at work 16% of the workforce

- Bedwas 75 men at work 13% of the workforce

- Markham 21 men at work 4% of the workforce

- Blaenserchan 8 men at work 2% of the workforce

- Oakdale 4 men at work 0.4% of the workforce

Six lodges in South Wales remained solid until the end, the only ones in the UK to do so, while another eleven were down to single figures.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page