On the 10th of October 1952 at 6.30 pm in a district being opened, there was an explosion at this pit which killed a deputy, Mr. A. Griffiths and severely burned several others.

On the 10th of October 1952 at 6.30 pm in a district being opened, there was an explosion at this pit which killed a deputy, Mr. A. Griffiths and severely burned several others.

At that time Bedwas employed 1,230 men underground and 263 men at the surface of the mine producing around 1,500 tons a day. The L21 coalface, where the explosion occurred filled out about 400 tons a day.

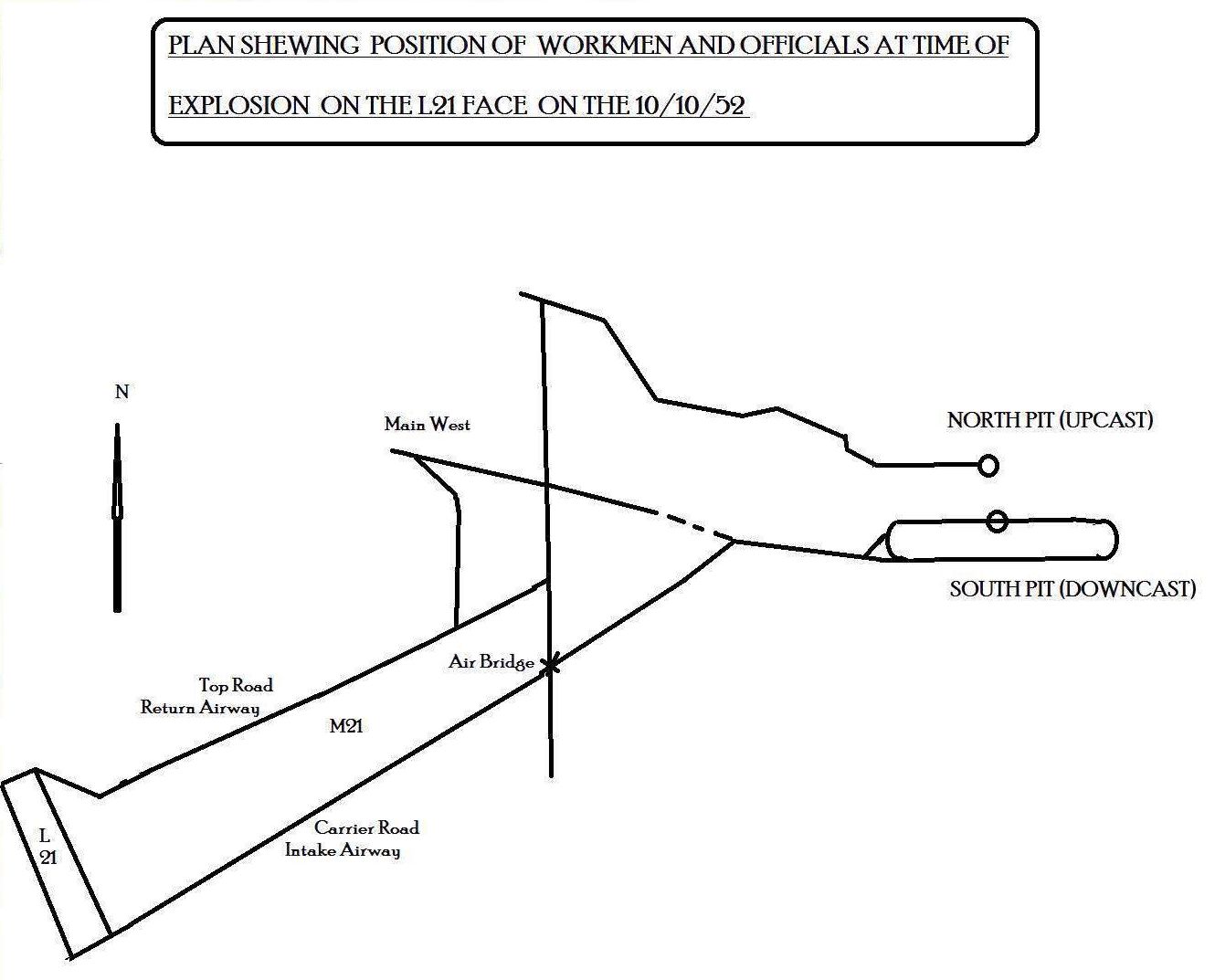

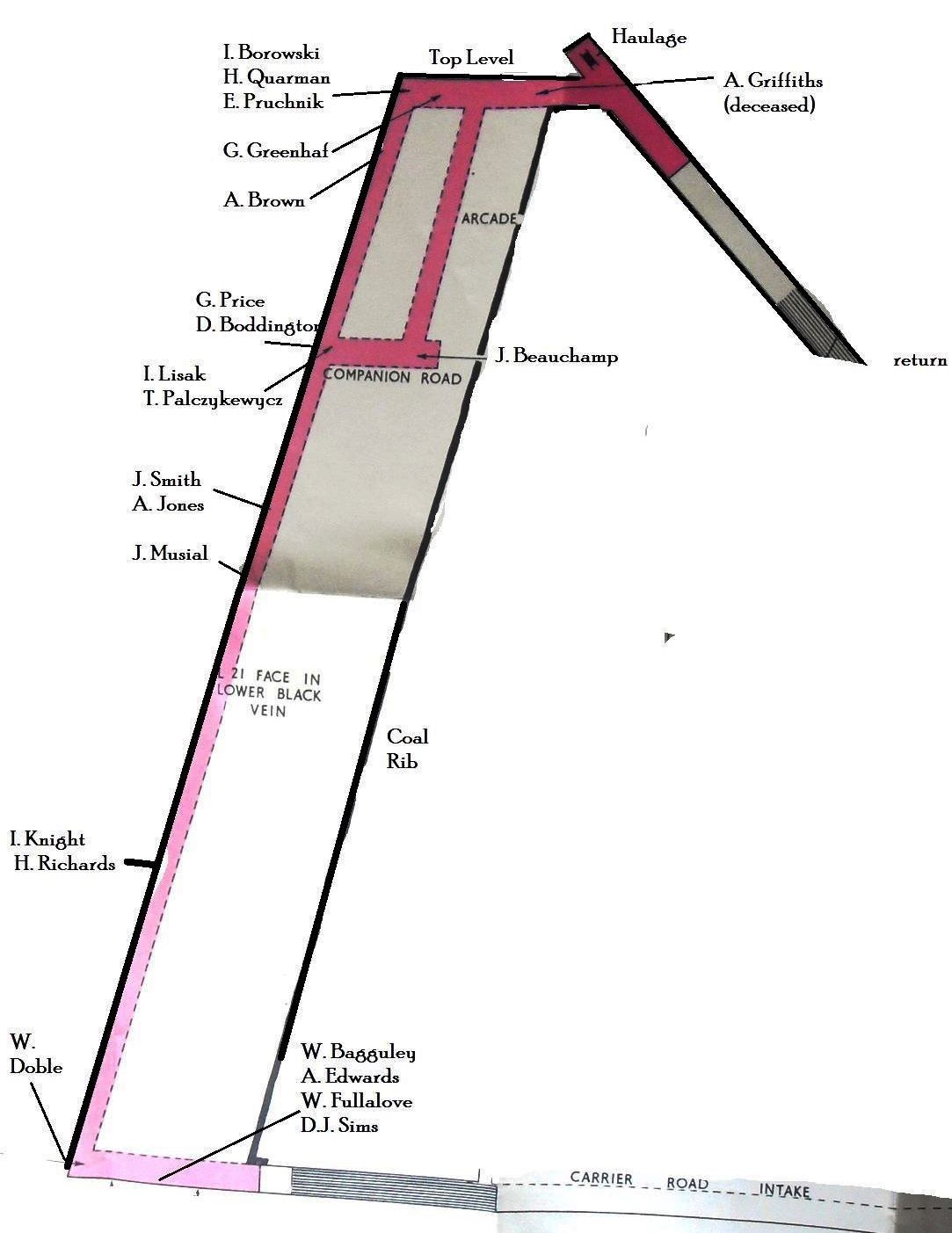

In the Meadow Vein (Yard/Seven-Feet) above the Lower Black Vein (Five-Feet/Gellideg) the M21 coalface hit a geological fault that brought the Lower Black Vein seam up to within ten feet of its workings. Due to the LBV being a better seam than the Meadow Vein it was decided to drive down into it and open up a new coalface called the L21. It had started on the 15th of September 1952 and at the time of the explosion, this coalface was 180 yards long, four feet high and had advanced 23 yards. The colliers worked the dayshift only and loosened the coal with compressed air operated picks and then shovelled it onto shaker conveyors, also operated by compressed air, which would carry the coal to the end of the coalface and from there onto a 350-yard long conveyor belt to the loading station where it was filled into trams.

The afternoon shift would advance the shaker conveyors ready for the next day, work on the roadways and packing areas while the nightshift also did some packing to support the roof and water infused the coalface to prevent excessive dust when the colliers broke up the coal.

Ever since the coalface had been opened there had been daily reports of diluted gas emitting from the roof of a blind heading used to house the haulage engine that brought supplies into the district. This was again reported on the day of the explosion and that was thought not to be a problem. The men were then distributed to their workplaces with an additional five men and a deputy brought in to clear off the coal left by the dayshift.

Just after food time, a 6.30 pm, the overman, Charles Jones, who was just outside of the district felt a ‘violent blast of air’ and realised an explosion had taken place. He immediately informed the manager on the surface of the mine and set the emergency procedures in operation. Two other deputies, E. Williams and I. Jones, bravely entered the area putting out small fires and came across the body of Arthur Griffiths. All the other men on the ‘face had suffered from burns but were fully conscious and able to walk out. Further investigation found that the flames had carried the whole length of the ‘face, thirty yards out into the carrier road and fifty yards down the tail road to the haulage house.

An extremely thorough examination was carried out into the cause of the explosion, with tests carried out on the safety and cap lamps, telephone system, signalling system and compressed air devices, but it all came down to an approved type of safety lamp which had no defects and was in good working order. The explosion was caused by an assistant surveyor relighting his lamp, in a legal manner, but it was found after exhaustive tests that in certain circumstances that type of lamp may cause an ignition of gas, the lamp, a Cambrian Midget Internal Relighter, was subsequently withdrawn from service.

Evan Williams gave this version of the events of that day which has been abridged by Ray Lawrence:

“I was a deputy or fireman in an adjoining district and was working there on this particular afternoon. It was a scene of horror which I shall never forget; an afternoon which I shall remember to my last day, and I thank God that he gave me courage, coolness, skill and resourcefulness to give help when so badly needed.

…Suddenly something happened! A tremendous rush of air stopped my breath for a moment; then the dust. I stopped. I wondered what had happened – someone had fired a heavy shot in the roof or something? An explosion never entered my head. What? An explosion in Bedwas? Impossible.

I turned back and ran to my telephone and tried to get communication anywhere. For a few minutes, I could get no answer – then, suddenly, I was plugged in and heard C. Jones, overman, asking for the manager. I interrupted the conversation and asked what was wrong, and as soon as he heard my voice, he said, ‘Come down here as soon as you can. Get all your men out and bring help.’ Even then I did not know what had happened. I sent the man off my engine into the district with an emergency call of All Out as quickly as possible and started to run towards the new district. I realised now that something serious was amiss.

As I ran onto the Main, I met a man walking out in a dazed condition. He was bleeding on the face and looked very much shocked. I went to him and, before I could say anything, he said ‘Don’t bother with me, Evan, let me go out. Go on down there. There’s worse than me.’

As I ran onto the Main, I met a man walking out in a dazed condition. He was bleeding on the face and looked very much shocked. I went to him and, before I could say anything, he said ‘Don’t bother with me, Evan, let me go out. Go on down there. There’s worse than me.’

The main rider and driver came running down then. I covered the injured man with coats and told these two men to keep him going to the top of the pit. I started to go down to the new district by myself when I met two more men staggering out…as soon as they reached me they said ‘Do something Evan, for God’s sake’. Their faces were burned, their hair was burned off, their arms and hands were blistered. I stopped these two men, and thereby the act of God was a large emergency First Aid Box hanging up on the side. I quickly opened this and obtained large mine burn dressings and bandaged them up. By this time some of my men had come. I sent them out with these two men and warned Men were lying about everywhere, moaning, groaning, some even shouting with terrible pain. Charles Jones, overman, said ‘do what you can for these men, Evan, I am going inside. There are more men.’ He called for volunteers and two men who had escaped injury went with him…I began to apply burn dressings as fast as I could…I now had the help of a fitter, G. Evans, who broke open bandages as fast as he could. Three men came down with a stretcher and I loaded up one of the men and sent them away with a verbal message for help, blankets and stretchers. Just then the rescue party with C. Jones came back out with two men badly burned, one was a Pole named Musial…The rescue party again went back in. Four men came in from outside with another stretcher. I loaded up another patient and sent him away. I had now used up all my first aid material…The stretchers were coming in now and I was able to dispatch the injured men with more speed, as soon as I loaded up a stretcher and covered over with blankets there was another one there until the last two men left were Long Shank Jones and his mate who had been lying side by side covered over with blankets all the time. Each time they said ‘We’ll go last’ they were the last to go – two wonderful men who stuck their frightful injuries without a murmur watching me send the other men away before them, someone had to be last, they preferred to wait. As they were loaded I started towards the face, as I got into the coalface I met William Doble coming down. He had gone back in with Charles Jones although he had been burned. He must have been made of iron, he went to pass me to go out. I asked him if there were any more injured. He said they were on top, and I saw that his hand and face and arms were burned and blistered. I seated him and bandaged him up with burn dressings and sent him out with two men towards the pit. I then passed on up the new face.

Near the top, I met the manager and shouted if he wanted me there, and he said ‘No go up to the top road.’ I reached the top road and there I found that they had laid A. Griffiths on a stretcher. He was dead. I made a quick examination and formed the opinion that he must have died instantly. The three other injured men had been sent out by another route to the pit bottom.

The National Mining Museum of Wales devoted one of their Glo Magazines to displaced persons who came over from Europe following World War Two. Quite a few worked at Bedwas Colliery:

Pal Czykewyck – The Whole Face was on Fire.

I was born in the village of Zawadiv in Ukraine, on 5 February 1927 to a farming family. I was still in school when the war broke out, but in June 1942 I was taken to Germany in a cattle train as a forced labourer in a market garden. It was hard work from seven in the morning until ten at night. I had no proper bedroom and I had to sleep in the attic. After the war, I went to a Displaced Persons Camp. Later we were asked which country we wanted to go to. I didn’t want to go back to Ukraine as I didn’t like Stalin or the Communists, having lived under them before the war, anyway I had heard that people who had gone back had disappeared! Even coming over here I had a map and was watching which way our train was going because the Russians used to divert the trains into East Germany. I used to make sure we were going the right way. I came to Britain and learned English in a school up in Yorkshire. I was given a choice where to work – a farm or a coal mine. Although I was of farming stock I didn’t like farming, I always wanted an engineering job, I went to Hawthorn Camp in Pontypridd and ended up in Bedwas Colliery. I met my wife Margaret who was living next door to me when I got proper lodgings. We got married in 1951 and have a daughter and two grandchildren. I worked at Bedwas with a good friend called Joe Lizak, I hadn’t been there a fortnight when it blew up. We were working a heading – it was very hot – poor ventilation. One day we were on stop because the surveyors came to do the point. I sat with my back to the coalface watching them. One of them was trying to light his lamp, it would light then go out straight again, he tried again it went straight out, he then blew in the lamp and tried again, nothing happened, he then blew it again, and tried again – suddenly a flame came out and the whole heading was on fire. I put my hands over my face, I had leather gloves on but I couldn’t save my ears and my body was burned as well – fifty per cent burns – There was a terrible noise like being next to a jet engine. Of course, there was gas, fire and dust, so the whole place was on fire, but it went out. Everything went dark. I was blind and panicked a bit, I couldn’t see anything. I followed the conveyor out but before I got to the end I saw a light, phew, that was joy, I started fiddling with my cap lamp and it came on. I walked through the face into the roadway and could see that help was coming – a bit late. All my skin was hanging, shirt burnt, bits and pieces. I was taken to Caerphilly Miners (Hospital) . I remember sitting, being bandaged up, then back in an ambulance to Chepstow.

My friend Joe Lizak was ok, but he didn’t have gloves and all his hands were burnt so badly they had to pull all his nails out. The surveyor who had the lamp in his hands, his hands were terrible, badly burnt. I was in a room on my own, they bandaged me up from bottom to top. I saved my hair because I had my helmet on, and my feet were alright because I had my boots on. My legs were burnt, my stomach was burnt, even my behind was burnt so I couldn’t sit on it and had to have a cushion, anyway I had a couple of operations. The worse was that they put me in a plastic jacket – I’ve still got the marks where the elastic was around it to stop the air from getting in. They fed me well, at first I couldn’t eat a proper dinner because my lips had shrunk. I had to suck with a straw. Got better so then I had good grub, they used to come back regularly and say you want more rice pudding? or second helpings? Yes! Every day I had egg and sherry, just to build me up. I don’t know how much weight I had lost, no strength, I couldn’t pick a mug up, terrible, but I came through.

When I came home I opened the coal house door and saw the coal. The shining hit me – frightening! So I didn’t go back (on the coal face) but went to work in the blacksmith’s shop instead. Welding everything- that’s what I wanted and stayed there until I retired. I used to work in the shaft looking after the pipes, bricks and ropes – I didn’t like shaft work but in the end, I even went down to pit bottom but I wouldn’t go any further in from there. When the pit closed I burnt the pit ropes – the cage was on a platform – on girders. So I cut the rope and that was that – no more Bedwas.

Theodor Palczykewyck

Return to previous page