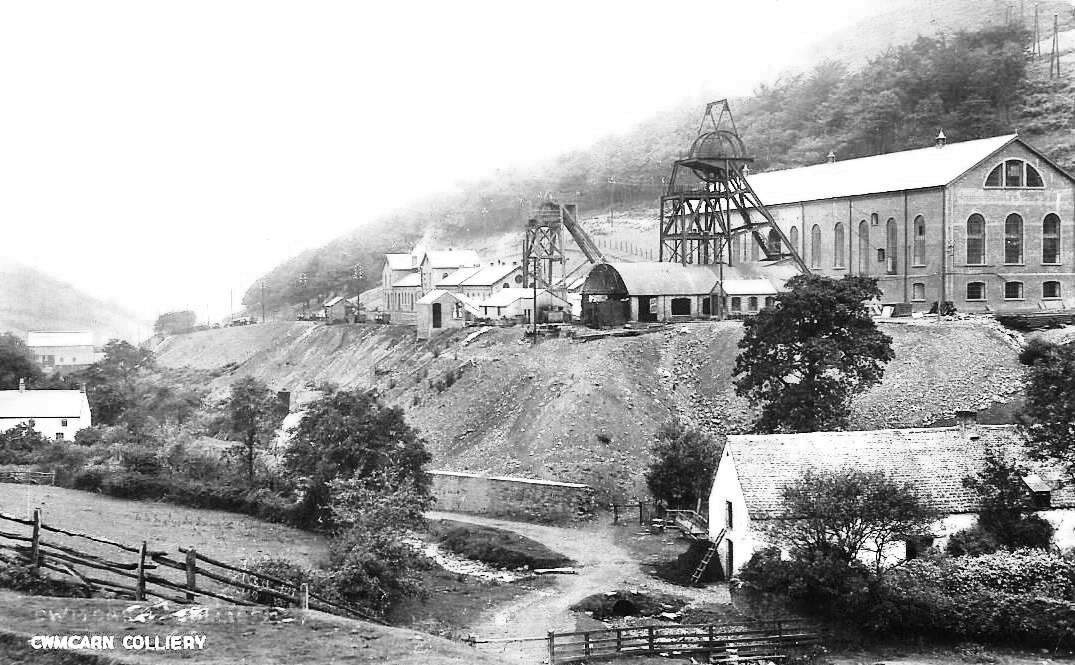

Cwmcarn, Ebbw Valley (ST 2364 9342)

Cwmcarn, Ebbw Valley (ST 2364 9342)

One of the two shafts of this colliery had been in existence since 1876 when at a cost of £60,000 it was driven as a second downcast ventilation pit for Abercarn Colliery (it increased the underground ventilation at Abercarn Colliery from 90,000 cubic feet of air per minute to 150,000 cubic feet per minute). It was 20 feet in diameter and was sunk to the Five-Feet/Gellideg coal seam which was locally called the Old Coal which was found at a depth of 272 yards. The Black Vein seam was struck at a depth of 247 yards.

During the sinking of this shaft, an explosion of methane gas occurred killing three of the sinkers. Mr. Cadman, Her Majesty’s Inspector reported:

After blasting at the bottom of the pit the place should have been examined with a safety lamp before open lights were taken down; the foreman, however, took a naked light as well as a locked lamp, no doubt believing all to have been safe, and a terrible explosion was the result killing him and two others.

A full report can be found here

The Ebbw Vale Steel, Iron and Coal Company decided to re-open the Cwmcarn shaft in 1909 with the first coal being wound up in July 1912. The plan was to raise 1,500 tons of coal per day. They then sank the second shaft at Cwmcarn to the Black Vein (Nine-Feet) seam. The sinking of this shaft, the upcast ventilation shaft, was completed in 1914. The winding engines for both shafts were electrically driven. Cwmcarn was one of the first collieries in South Wales to have electricity powering its machinery and it also supplied the first electricity to domestic dwellings in the area. From that date on Cwmcarn Colliery worked as a separate unit to Abercarn.

The No.1 shaft was at grid reference ST23679341, the surface level was 526 feet above OD level, and the winding level was at the Black Vein seam, while the depth of the shaft was 246 yards. The No.2 shaft was at grid reference ST23639342, the surface level was 527 feet above OD, and the shaft was sunk to 278 yards.

The Company also constructed the Garden Suburbs at Pontywaun to house the officials of the new colliery, the style of architecture used was lauded at the time as a prime example of the arts and craft style of the Garden City Movement whose aim was to improve the standard of homes for the ordinary people. A detached house called the Homestead was built for the manager of the mine. This area was the first to have electricity in their homes and is now a listed buildings site.

The railway line linking the colliery to the main railway at Pontywaun was on the south side of the Nantcarn Valley, the route of which is now used by the Forest Drive entrance road. The wagons would be taken past the colliery by the mainline locomotive and then gravity fed under the screens for filling before being taken away. On the surface, the ‘washery’ was supplied with coal by the long by the longest single conveyor belt in the country. As the colliery buildings and its associated ‘waste’ expanded, the Cwmcarn Farm was acquired and was buried under coal ‘spoil’. Underground conveyor belts gradually replaced the pit ponies for hauling the coal from the coalfaces. There were 40 ponies working underground in 1940, and only a few ponies still working in 1963. The last working pony was brought to the surface for the final time in 1965.

Cwmcarn Colliery was developed into an independent unit in 1912 and total manpower in the company’s eight mines totalled 5,397 in 1913. The early 1920s brought about the acquisitions of the Newport Abercarn Black Vein Steam Coal Company, John Lancaster and Company and Powell’s Tillery Steam Coal Company; they were then run as subsidiary companies. In 1935 the mining interests of the Ebbw Vale Steel, Iron and Coal Company were bought by Partridge, Jones and John Paton and Company. At that time the company employed 6,820 men and produced 1,940,000 tons of coal, while the three subsidiary companies employed 7,325 men and produced 1,950,000 tons of coal. The Board of Directors consisted of; Chairman and Managing Director, Sir John W. Beynon. Directors, Sir Arthur Lowes Dickinson, David H. Allan, Trevor L. Mort, Secretary, Richard Green, Commercial Manager, P. Fernihough. In 1920 Partridge, Jones and John Paton was formed by the Amalgamation of the Crumlin Valley Colliery Company with Partridge, Jones, who then owned Crumlin Navigation, Gwenallt, Blaenserchan and Llanhilleth collieries. Partridge Jones and Company began trading in 1864 at the Varteg Works with a partnership of Partridge, Bailey, Jones and Messrs. Henry. In 1874 they expanded and controlled the Pontnewynydd Iron Works, Golynos Iron Works, Abersychan Iron Works and both Plas-y-Coed and Cwmsychan collieries. In that year a limited company was formed. John Paton by 1895was one of the principal shareholders in the Pontnewynydd Sheet & Galvanising Works with Partridge, Jones, and with the death of W.B. Partridge in 1909 obtained a seat on the board of Partridge, Jones & Co. In 1920 the interests of both companies were amalgamated. They owned Cwmcarn Colliery until Nationalisation in 1947.

In August 1913 Bert Davies aged 22 years, and a haulier turned the track points on the underground tramway the wrong way and was crushed to death by the journey, one of the first fatalities in the new colliery. The manager at that time was E.W. Broackes who was still there in 1916. At that time Cwmcarn employed 292 men out of a total manpower of 5,397 employed by the Ebbw Vale Company in their 8 pits.

The colliery and the village were now taking shape, at the colliery, the usual South Wales men v owners battle lines were drawn up, the owners prosecuting men if they stepped out of line, Charles Taylor had a 20 shillings fine at the magistrate’s court for falling asleep on the nightshift, and two men, John Davies and John Ryan were prosecuted for accidentally damaging their safety lamps. The union refused to work double shifts on the coal sticking to one shift despite managements request and forwarded a pile of complaints on to the Federation agent to deal with but, due to the war effort, decided not to strike at that time. The village was spreading, gas had been installed in Nantcarn Road, and in the new houses of Park Street and the council was considering acceptance of the Ebbw Vale company’s offer to sell them land at Chapel Farm to build houses on. The shortage of housing was pretty acute, with the housing officer complaining of cases similar to oneof the three-bedroom house in Park Street that housed seven adults and four children. In January 1914 there were 47 new babies in Abercarn and Cwmcarn and 22 deaths, 9 of them due to coal dust on the lungs.

In October 1915 the colliery was shut down for a while due to the shortage of ships at Cardiff docks. Unfortunately for young Nehemiah Churchill aged 14 years, it was working again in the following November, Nehemiah was working at the coalface with his father when the roof collapsed and killed him. His father was unhurt. This had followed the death in January 1915 of David Pretty, aged 12 years, and a cog setter, he had slipped on a tram rail and fell onto a hatchet. It caused a deep wound to his left leg. After several weeks off from work he started back but the wound re-opened and he returned home. He died later that week. The doctor at the Inquest claimed that the wound had healed perfectly and the signs were that he had died of pneumonia.

In July 1915 the South Wales Coalfield came under the Munitions of War Act after an Area Conference called for a new wage agreement. Following a five day strike, the Government concedes the main demands. In November the South Wales Coalfield is brought under State control. In 1918 Cwmcarn colliery employed 590 men underground and 125 men on the surface with the manager being G.H. Simpson.

There was a multiple fatality at Cwmcarn on the 9th of March 1923 when both William Pitman and Harry Jones died under a roof fall:

CWMCARN DOUBLE FATALITY. A The circumstance. of the double fatality at Cwmcarn Colliery, of which the victims were William John Pitman (48), fireman„ of Park Street, Cwmcarn, a married man, and Harry Jones (37), engine driver, a single male, whose widowed mother lives at Crosskeys, were investigated by the Coroner (Mr. D. J. Treasure) at. Abercarn Station on Monday evening. Edward George Barter, colliery fireman, of Nantcarn Road, Cwmcarn, said Pitman was the certificated shot-firer at the colliery and was usually assisted by Jones. At 8.30 p.m. on Wednesday both men were preparing for shot-firing, and witness accompanied Pitman to examine the place, which he found safe. The last pair of timber was close to the face. Witness returned to the district at 10 p.m. and discovered that a fall had taken place, consisting chiefly of a stone four feet by six feet and weighing about two tons and that deceased were underneath. He ran for assistance, and the men were eventually released, but both were dead. The witness was the last Man to examine the place and the first on the scene after the fall. He examined the place after the accident and found no indication of a slant. The Coroner: What is your theory of the cause of the fall? Witness: A ” bumper “disturbance of the ground. Sometimes they are heavy and sometimes light. Replying to Mr. Greenland Davits (H.M. Inspector of Mines), the witness said he discovered that the men had fired two shots, and judging from the position of the bodies he thought they were charging the third when the fall came. Mr. Opton Purnell (miners’ sub-agent): Do you think the hole which was bored in the centre might have disturbed the stone?—There is a probability. Mr. J. G. Simpson, the colliery manager, said they were positively certain that the men had only fired two shots, and were charging the third. The Coroner said he was happy to be able to say that no blame was attached to the fireman. who made a thorough examination. Everything possible had been done to prevent an accident. It was an extremely sad case, and the first that he (the Dormer) had come across was where two were killed by the same stone. He expressed sympathy with the relatives and mentioned that Jones’ mother was 80 years of age, and had been mainly dependent on him for support.

Mr. Simpson was still there in 1923 while H. Davies was the manager in 1927/30. On the 9th of November 1928, Thomas George Moses, a collier aged 29 years died under a fall of roof, while almost a year later on the 7th of November 1929, Ivor Gregory, a colliers assistant, aged 23 years, also died under a fall of roof.

In 1935 Cwmcarn employed 800 men underground and 100 men on the surface and was managed by H.G. Davies. In 1938 it was managed by R. Rees, and in 1943/5 by D. McNeil when it employed 532 men working underground in the Black, Five-Feet, Meadow Vein and Big Veins and 90 men working at the surface of the mine. The colliery re-worked the Abercarn Black Vein seam until c1942. This seam had an average thickness of 84 inches and Cwmcarn re-worked it near the old Abercarn Colliery’s Nos.17 and 21 Districts where the 1878 explosion occurred. These workings were carried out between 1931 and 1938 and several items were discovered in the old workings including an oil lamp that was given to the Mines Inspector in 1933 and an old tram found in 1937 and brought up Cwmcarn Pit. One collier is reported to have opened an old air door that had been sealed with debris over the years to find a horse standing behind it. As soon as the air made contact with it the horse crumbled into dust. Strangely no human remains were found, but there was also a rumour that a devoutly Christian miner when he came across human remains simply said a prayer and reburied them in that area. There is a possibility that this could be true, for at the neighbouring Abercarn Colliery the remains of three miners were cynically boxed and left in the surface stables and forgotten about until discovered by accident in 1950.

The Big Vein or Four-Feet seam was worked between 1923 and 1929, and again in the 1950s and 1960s. It had an average thickness of 36 inches. The Upper-Three-Quarter seam was extensively worked in the 1920s and 1940s to 1960s. It was just over 15 feet below the Big Vein and again averaged around 36 inches in thickness. The Lower-Six-Feet seam was about 13 feet below the Upper-Six-Feet and averaged 28 inches. Attempts to work the Meadow Vein and Old Coal seams were carried out in the 1940s with little success due to the poor geology. The Meadow Vein had a thickness of 36 inches and the Old Coal seam a thickness of top coal 21 inches, dirt 8 inches, bottom coal 25 inches.

At that time Cwmcarn pit employed 79 men on the surface, and 526 men underground working the Nine-Feet, Five-Feet, Yard/Seven-Feet, Four-Feet and Two-Feet-Nine seams.

In 1951 there must have been criticism about the use of horses at the colliery with the manager replying:

Pit ponies Sir.—Recent letters regarding ponies at the Cwmcarn Colliery are misleading and I would draw it your attention to the following:—Horses are entirely eliminated from the transport of coal at Cwmcarn Colliery. Such progress has been made with mechanisation that the entire pit output is got onto a central conveyor loading point, dispensing with the use of horses. It is true five are still retained for use in the dismantling of districts. and when such is completed horses will be entirely withdrawn from the colliery. It is wise to remember that 15 years ago there were 40 horses employed at the colliery H. J. J A (Manager. Cwmcarn Colliery).

It was managed by D. McNeil. In 1956 out of the total colliery manpower of 561 men, 253 of them worked at the coalfaces, in 1958, 250 men were working at the coalfaces, and in 1961 out of the 453 men working at the colliery 190 of them were at the coalfaces. In 1961 this colliery was in the No.6 Monmouthshire Area’s, Abercarn Group, along with Celynen South, Celynen North, Crumlin Navigation, Aberbeeg South and Graig Fawr collieries.

The total manpower for this Group was 3,193 men, while total coal production for that year was 772,000 tons. The Group Manager was G.H. Golding, while the Area Manager was Lister Walker.

When the Coal News came to a visit in 1954 the reporter commented that:

Cwmcarn Colliery nestles at the end of a spur of the lower Western Valley. The plantations of the afforestation scheme crown in upon the colliery, and sheep crop the short grass a dozen yards from the pithead. Competing with the noise of the screens was the sound of a bulldozer in the forest, making a road through regiments of trees.

I noticed something odd about Cwmcarn-the absence of a waste heap. And my guide, chubby Welsh-speaking Area Welfare Officer Emrys Davies, that the reason has always been simply lack of space-so that during its lifetime all Cwmcarn’s waste has been hand stowed underground.

There was an investment into the pit in 1957 when at a third of a mile, the longest colliery surface conveyor in Britain has been put to use at Cwmcarn colliery. It replaces the old tram road and tram system.

1963 was a very bad year for this colliery, in July, John Bourne aged 44 and a colliery ripper, was killed when a large stone fell on him from the roof. He was married with two children. At the Inquest held at Blackwood a verdict of accidental death was recorded. William Charles Thomas who was working with Mr. Bourne driving a heading said shotfiring had taken place and they were clearing loose coal Later when Mr. Bourne was using a blast pick a large stone fell from the roof on top of him without warning. He was dead when freed. A colliery deputy said that the stone weighed about 30 cwt and had to be moved mechanically. Recording the verdict the coroner said that there was no carelessness or negligence on anyone’s part.

Harry Sims a signal worker was crushed by a journey of trams also in July 1963. His job was to regulate the flow of shale into drams. William John Lewis a rider told him that he was going to unhook several trams from the journey however he had to wait ten minutes until some shift workers were clear. he signalled to move when suddenly there was a shout and the trams stopped. Another man said just before they moved he saw Sims standing on one oiling a metal lip. When they moved he was crushed between them and the lip. He died several days later in hospital. Accidental Death was the verdict.

1963 was also the year that compulsory retirement at 65 years was brought in. for Cwmcarn that meant that 58 men were left with little chance of filling their jobs with new labour. In 1965 the National Coal Board made a detailed survey of each colliery and its potential and placed them in three categories, A, B & C.

Cwmcarn Colliery was placed in Class B. CLASS B consisted of 19 pits, these are pits that face a doubtful future either because of difficult geological conditions or that special effort is needed for them to pay their way and win a secure future. in 1965, the aura of uncertainty caused by the apparently random way that collieries were closed created a despondency amongst the men that caused them to leave the industry in droves, with the resultant closure of potentially profitable pits so that their manpower could be used to fill empty places at neighbouring pits. Such was the case with Cwmcarn which was used as a manpower reservoir for such pits as Bedwas and the Celynen South.

Up until closure, the coal was hand-filled onto conveyors on the coalface on the day shift only. On the backshifts the coal would be undercut up to four feet deep by a coal cutter and allowed to fall loose, the colliers on the dayshift would then fill the coal onto the conveyor on the coalface. They would also hack down the coal that hadn’t fallen with a mandrill and erect supports in the form of wooden props to protect themselves. The area or stent that they would work depended on the thickness of the coal but was normally between seven and nine yards long. The coalface conveyor would then take the coal to other conveyors and eventually to a ‘dump end’ where the coal would be filled into trams. When 28 trams had been filled they were attached to a rope and a rope from a haulage engine would be attached to the ‘journey’ and take them to the pit bottom where they were wound up the pit. The next shift going onto the coalface would then partly dismantle the conveyor and push it forward ready for the next cycle of operations, they were called the turnover gang. The roof supports were taken down and moved forward with the advancing coalface and the roof behind was allowed to fall, except for the two roadways on either side of the coalface which were used for ventilation and to bring men and materials in, and the coal out. They were normally called the dump road (where the conveyor was) and the tail road (where the supplies such as timber came in). Towards the end of the life of the colliery another method called narrow work was used in that headings or roadways were driven into the coal, boreholes were then driven into the coal and explosives used to loosen it. The coal was then loaded onto Samson loaders which consisted of two rotating steel ‘gathering arms’ that scooped the coal back onto a metal conveyor that was part of the machine, the coal was then dumped onto a belt conveyor and out to the dump end. This method was used near to the outcrop of the coal and could encounter areas of coal 30 feet thick, the coal could also rise in parts almost vertically making it very dangerous to work due to it falling on top of you. As you neared the outcrop of the seam the coal would go from rising one in two and a half to one in one and a half.

Cwmcarn Colliery was a small close-knit unit, which, coupled with its remote position made it a law unto itself in many ways. For example, my father was given a job to lay some rails for a tramroad underground, and a contract (price) was agreed upon. The following Friday when he received his pay he hadn’t been paid for the job so on the Saturday morning he went down the pit and tore the rails up. Whereas in most places he would have been sacked, instead he got his money!

Cwmcarn Colliery was closed by the NCB on the 30th of November 1968 as being uneconomic. The shafts were filled with the waste from Hafodyrynys, Bedwas, Nantgarw and the Celynen South washeries (which was called tailings) 108 lorry loads raised the level of the downcast shaft by 70 feet in the week-ending 15th May 1971 and completed the filling of that shaft. It was later to be grassed over and partially landscaped, with the entrance to the Cwmcarn Scenic Forest Drive going over the top of the now filled in shafts. Most of the men were transferred to Oakdale 23, Bedwas 24, Glyntillery 7 and Celynen South 100, collieries, sixty of the men retired early and sixty were retained temporarily on salvage work.

The Cwmcarn Forest Drive was opened in 1972, and reclamation schemes taking place on the site between 1972 and 1979 removed the derelict colliery buildings and created a small lake in the base of the valley as an additional amenity for visitors and local inhabitants to enjoy.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page