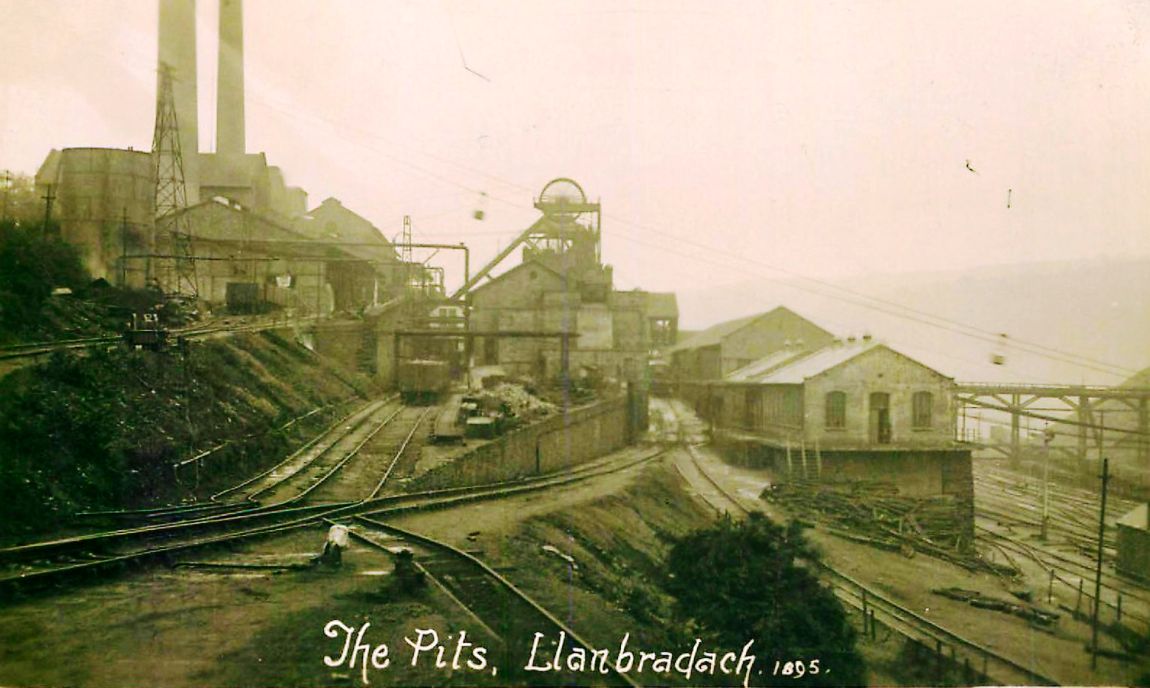

The first shaft of this colliery to be sunk, the No.1, was 570 yards deep and 17 feet in diameter and was completed in 1893. The No.2 Pit was 20 feet in diameter and completed to a depth of 584 yards in 1894. The total cost for the sinkings was £270,434. The winding engines were steam-driven and of the compound type, only the second of this type to be used in the South Wales Coalfield.

The first shaft of this colliery to be sunk, the No.1, was 570 yards deep and 17 feet in diameter and was completed in 1893. The No.2 Pit was 20 feet in diameter and completed to a depth of 584 yards in 1894. The total cost for the sinkings was £270,434. The winding engines were steam-driven and of the compound type, only the second of this type to be used in the South Wales Coalfield.

From the start the venture didn’t go as planned, at a depth of 50 yards they hit a feeder of water and were delayed while pumps were installed, despite predictions that all would then go to plan there were further holdups, the ground was harder than it was at first thought, other feeders of water were hit, and crucially the seams were further down than had been predicted.

The No.1 Rhondda or Rock Vein seam was a fine house coal seam that was found at a depth of 791 feet so was the first coal seam to be developed. But again the production figures didn’t reach what the company expected and the workings in this seam were closed in 1902.

It had reached a figure of 128,500 tons of coal produced in 1897 but by 1901 this figure had dropped to 42,200 tons. The Five-Feet seam, with a thickness of five feet, was the first steam coal seam to be developed in 1894 followed by the Upper-Nine-Feet seam, also five feet thick in the following year.

The original ventilation fan was a Guibal type measuring 40 feet in diameter and 12 feet wide. Around 1915 the fanhouse was reconstructed to house two electrically driven fans that replaced the original steam-driven one. The new fans were of the Sirocco type and a Walker Indestructible as standby.

The Western Mail newspaper on the 28th of January 1890 reported;

Considerable excitement was caused at Caerphilly on Monday by a report that a four-foot seam of coal had been struck at Llanbradach Colliery. On one of our representatives making enquiries, it was ascertained that the rumour had been exaggerated. Coal had been found, but on examination, it only proved to be a small vein, about 14in. in thickness. This, however, is a good sign, the coal being similar to the strains existing in the Rhondda. The depth of the shaft is now about 400 yards.

On the 19th of June 1891, an explosion of firedamp killed William Henry Smith, a pumpman; it appears that he went underground to the pumphouse with an unlocked safety lamp which caused the explosion so severe that the colliery did not restart work until early August. At the Inquest, the jury returned the verdict of:

The deceased died from suffocation by afterdamp following an explosion of gas caused by his having a naked light in the pumping station in which he was employed at the Llanbradach Colliery. That there was gross negligence on the part of those who were responsible for the management of the colliery previous to the explosion, seeing that many of the rules of the Mines Regulation Act, made for the protection of life, were systematically broken.

In October 1891 the two senior officials at the mine, William Galloway, consulting engineer, and Stephen Wilson the manager, were summoned by the Inspector of Mines for breaches of the Mines Act concerning preshift inspections, the general supervision of the mine, and over the use of safety lamps. The case was heard at Caerphilly Police Court. The prosecution and the defence then colluded and agreed that it was a technical offence only regarding the lamp and in no way was it linked to the recent explosion, they then dropped all other charges and asked the bench to be lenient with Mr. Galloway. He was fined one shilling with no expenses.

William Galloway was born in 1840 in Paisley, Scotland, and was educated in Scotland, Germany and England to qualify as a mining engineer. His career started back in Scotland as a colliery manager and then a mines inspector. Following two terrible explosions in the South Wales Coalfield in 1875 Galloway was called in to investigate them and to report his findings to the inquests. He became an Inspector of Mines for South Wales before accepting the position of Professor of Mining at the University College of Wales. His major speciality was in work to prevent colliery explosions, particularly with watering roadways to prevent coal dust from spreading explosions throughout the mine. It was mainly due to that research that he was knighted in 1924, albeit at the age of 83 years.

In the early 1920’s he became chairman and director of the East Kent Colliery Company and a director of the Snowdon Collieries Ltd. He died in 1927.

There was a slight setback in the sinking of the shafts in August 1893 when the water tank that was bringing the excess water up the pit was overwound and went over the headgear sheaves in the No.2 Pit. The winding machinery was badly damaged and the rope and water tank fell back down the pit. Luckily there were no men down the pit at the time. It cost £400 to repair the damage. 1893 was the first year of coal production, with 27,651 tons being raised in the end bit of the year.

In May 1895, at a mass meeting held at the Pontygwindy Inn, the workforce at Llanbradach decided to join a union, the South Wales and Monmouthshire Colliery Workmen’s Association, with a view to bettering their position in respect to the double-shift system worked in the stalls at the colliery.

In 1896 it was managed by G. Bradford and worked the No.3 Rhondda, Upper-Four-Feet, Six-Feet and Nine-Feet seams.

An unfortunate fatality occurred at this colliery on the 2nd of December 1897 when Edward Blackwell aged 34 years and a hitcher fell into the sump at the bottom of the shaft and was scalded by hot water being discharged from a pumping engine, he survived this but “He walked home through the frosty atmosphere without applying oil or taking other precautions, and died the next morning.” A few weeks later on the 29th of December, Enoch Davis, a 29 year old haulage rider was crushed to death by a tram of coal.

To highlight the callousness of the coal owners of those times just look at an incident on the 28th of September 1898 When Thomas Powell aged 25 years and Owen Arthur Davies aged 34 years were thrown out of the cage that was taking them down and killed when it hit the Four-Feet landing. The official report stated that “No other damage was done and winding proceeded in the ordinary course.”

In 1899 there were widespread strikes throughout the Coalfield over the hated ‘sliding scale agreement’ in which the wages were tied to the price of coal. This system seemed logical but it was manipulated by the coal owners who would drop wages as soon as the price of coal dropped, but would not give a wage increase for a few months after the price of coal had rose. With the men out at Llanbradach, this was reported in the Western Mail on the 17th of August 1899:

The officials of this colliery have assumed a very determined front. Fires have been put out, day men, engine-men; in fact, all the employees have been paid off. From the time these pits were started, about seven years ago, nothing but misfortune has been encountered. Instead of raising about 700 tons a day, the output the week before the men were called upon to discontinue only reached something like 150 tons.”

With the strike settled things got back to normal and full production resumed with a respectable 430,000 tons of coal, hewn out by 1,600 men produced in 1900.

On the 10th of September 1901, an explosion claimed the lives of 7 men. The explosion was caused by shotfiring; the full report can be found here. Also that year on the 9th of January Fred Tilley, aged 58 died when run over by trams, on the 19th of January Thomas Whitney aged 45 years was run over by trams, on the 28th of January Dennis McCarthy a timberman died under a roof fall. On the 12th of March Henry Jones, aged 30 years died under a roof fall, on the 2nd of July Garnet Miles aged 16 years died under a roof fall. In 1913 alone, no less than 35 men from this pit were fined for having matches in their possession whilst underground.

From 1913 the colliery slowly failed to achieve its former production heights with firstly the 1914 -18 war reducing its manpower, and following that the industrial disputes and trade recessions that ravaged the 1920s and 1930s. The output of coal did lift again towards the end of the 1920s, with 690,700 tons being raised in 1929, but this figure can be attributed to the house coal pit (No.3) going into production along with the steam coal pits.

In November 1921, the 2,200 men at this pit were locked-out and had to agree to improve output and fill clean small coal in the future before they could re-start. From 1923-1927 the manager was E. Watkins.

The No.3 Pit was sunk to work the Nos.2 and 3 Rhondda (Big and Little Rock) seams between November 1923 and May 1925 to serve as the house coal pit for the colliery. It was 260 yards deep and cost £73,000 to sink.

The takeover by the National Coal Board improved the life of the Llanbradach miner with baths, canteen and medical centre constructed on the surface and new machinery installed underground. Yet it didn’t stop industrial disputes from happening, and as soon as August 1948 the men were out on strike over a deduction of 24 shillings from the wages of eight colliers due to them leaving their workplaces early. Following two days out on strike they obeyed the unions call to go back to work to enable negotiations to take place. In January 1951 the pit was again on stop, but this time due to many of its workforce catching influenza.

In 1954/55 this colliery was one of 42 that caused concern to both the NUM and the NCB over the high level of accidents. In 1954 manpower had dropped to 225 on the surface, and 914 men were underground, with the No.1 Pit working the Nine-Feet seam, the No.2 Pit working the Six-Feet seam, and the No.3 Pit still working the Big Rock seam. The manager was H. Monte. The annual output of coal for 1955 was 322,000 tons the highest production figures at this colliery since nationalisation. From 1947 the output per man shift had also increased from 15.5 cwts to 24.7 cwts.

The colliery was rewarded by the installation of new pit head baths, medical centre and canteen costing £92,000. They were opened in August 1955.

In 1955 out of the total colliery manpower of 1,074 men, there were 466 of them working at the coalfaces. In 1956 the coalface figure had risen to 509, but it dropped back to 432 in 1957, and further down to 381 men working at the coalfaces at this colliery in 1958.

The Rock Vein or No.3 Pit was closed in May 1960 due to the intrusion of thick dirt into the seam. At closure the section of this seam was:

- top coal 11 inches

- dirt band 36 inches

- coal 18 inches

- dirt 5 inches

- bottom coal 6 inches.

In November of 1961, the NCB claimed that there were 5,681,000 tons of coal left in the Six-Feet seam (1,339,000 tons were recoverable from Windsor) and 5,501,000 tons of reserves in the Four-Feet seam (2,308,000 recoverable from Windsor Colliery) and 7,450,000 tons of reserves in the Nine-Feet seam (2,995,000 tons recoverable by Windsor).

The NCB looked at ways to keep the pit open and even suggested integrating it with Windsor Colliery, however, this option was withdrawn and the NCB claimed that £2.5 million would be needed as investment and that there were not enough men working at the colliery to justify that expenditure. They stated that the pit was uneconomic and conditions at the coalfaces were deteriorating and that the men would be better off at Windsor, Britannia, Penallta and Bedwas Collieries. The S5 coalface had hit washouts, the S71 the same and the S20 had geological difficulties.

Llanbradach Colliery was closed on December 29th 1961 and most of its workforce was transferred to Britannia and Wyllie Collieries.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page