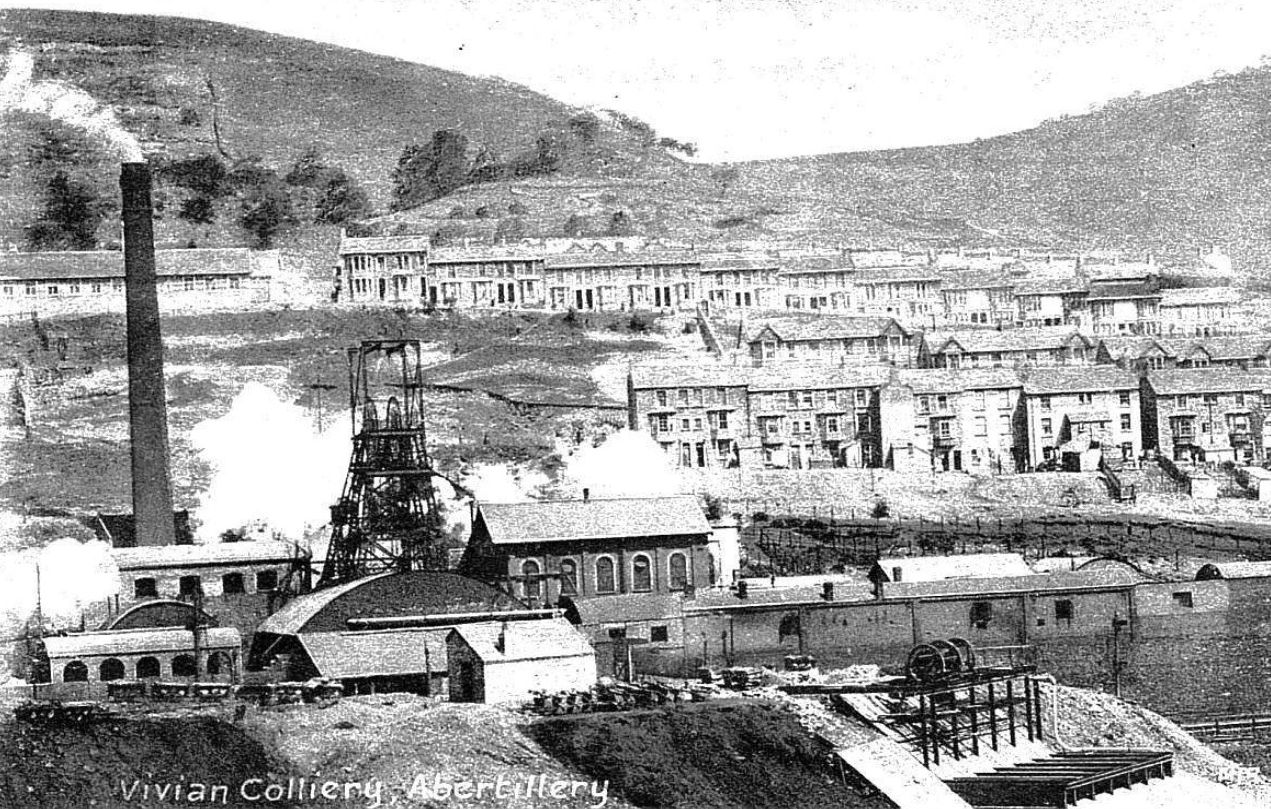

Vivian Colliery was sunk in 1889 by the Tillery Coal Company Limited, with the first coal being raised in 1891. It was linked to the Grey Pit. The one shaft was sunk to a depth of 324 yards (296.4m), the Four-Feet seam was struck at a depth of 230 yards (210.5m), the Nine-Feet seam at a depth of 275 yards (252.3m), and the Five-Feet/Gellideg seam at a depth of 322 yards (294.4m).

As usual, a great deal of ceremony accompanied the starting of the sinking operations with the formal cutting of the first sod. Many dignitaries were brought from Newport and Cardiff to witness a Miss Alice Hacquoill (daughter of the Cardiff Agent for the Company) do the honours followed by Miss Dawson (daughter of the company manager) and E.C.P. Hull a director of the company. Thomas Powell Junior was in Australia and missed the ceremony which included both the Gray and Vivian pit sites. A short service was then given by the vicar Mr. Walters and gold coins were placed in the holes made by the sod cutting. This was meant as a gift to the sinkers, a North of England firm run by Mr. F. Coulsom. Sinking came to a halt in the November of that year when they hit watercourses in the shaft. To overcome this it was decided to increase the diameter of the shaft so as to accommodate the pipes associated with the pumping equipment that had to be installed.

A very serious incident occurred on the 7th of December 1890. As per usual holes were bored into the floor of the shaft, explosives and then ‘stemming’ was packed into the hole behind the explosives and then the men were brought to the surface and the explosives fired by the used of an electric shot firing machine. The day shift took over operations and went down the shaft at 6 a.m. and started to clear the debris that had been loosened by the shot. All went as normal until 1 p.m. when an explosion occurred killing three men and injuring the others. It was believed that one of the explosives had failed to explode when fired, and had then been hit by a metal tool which caused it to go off. Those that died were; James Bannister, Thomas Rees and George Millard.

The main seams to have been worked were:

- Five-Feet/Gellideg (Old Coal) which averaged a thickness of 56 inches and Yard/Seven-Feet (Meadow Vein) seam which averaged; coal 36 inches, clod 8 inches, coal 24 inches.

- The Elled seam was 57 inches thick, while the Black Vein was generally absent.

- The Big Vein group of coals consisted of, from the top seam; coal 33 inches, clod 17 inches, coal 42 inches, rashings 18 inches, fireclay 44 inches, ground 20 feet,

- Three-quarter seam, coal 42 inches, clod 6 inches, coal 6 inches, clod 48 inches,

- Lower Three-quarter coal 26 inches.

In September 1897 the workers at Cwmtillery and Roseheywirth found out that the Vivian men were earning more money and working fewer hours than them. They went out on strike but failed to gain parity. The Vivian men worked an average of 54 hours a week while the others worked 58 hours a week on average. On top of this the Vivian men earned 2.5 pence an hour more in wages.

In 1904 it was owned by Powell’s Tillery Steam Coal Company who set about increasing output and modernising the plant.

In 1909 an aerial ropeway was constructed to take the colliery waste to the top of the Arrael Mountain. 12 stands, each 50 feet high were used to carry the waste 800 feet up the mountain at an average gradient of 1 in 5. The drive engine was 100 h.p. and used to haul 8 hundredweight capacity buckets at a rate of two a minute up and down the mountain. It had a friction clutch so that the buckets could stop more or less immediately. Tipping was only done by day and a storage bunker was installed by the engine house to accommodate the waste from the back shifts. Only four men worked on the ropeway.

Horse power was largely replaced by steam-driven haulage engines based at the surface of the mine. The rope was conveyed down the shaft in tubes and then ran along the haulage planes to the districts. Instead of opening up a landing in the shaft to fill out the Black Vein coal, they sunk an underground shaft called a staple pit, which dropped the Black Vein coal down to the Old Coal level from where it was taken to pit bottom. At that time it employed 547 men underground and 60 men on the surface. The manager was E.B. Lichtenberg.

The Ebbw Vale Company were concerned about the ventilation system at this colliery and in 1923 they installed a new ventilating fan at the upcast shaft (the Gray), this didn’t quite do the trick so in 1929 they drove a new connecting roadway between the two pits.

In 1904 the colliery was still in the hands of Powell’s Tillery Steam Coal Company Limited who by 1913 employed 1,889 men at Vivian, Tillery and Gray Pits, the manager at that time was Tom Evans.

In April 1914 the men posted notices around this pit to advertise their big demonstration that was arranged for May Day. Management promptly tore them down so the 2,500 men at Vivian, Tillery and Gray went out on strike. The posters were put back up.

Mr. Evans was still the manager in 1916 when collectively they employed 2,600 men.

The Twentieth Century had just begun and the World demanded more and more south Wales coal, the Bristol Channel became the busiest waterway in the world and the South Wales Coalfield was the top coal exporting area in the world. The coal industry and this area was at its peak, jobs were plentiful and people flooded into the Valley.

These were the so-called ‘good old days’ perhaps they were for some, but wages were still poor, most housing sub-standard and health and educational facilities second rate. Whether they were the good old days or not, it now went all wrong – big time – the Great War was over, reparations in the form of German coal cancelled out some markets, other markets were seduced by cheap coal from countries desperate to rebuild their economies and the USA had virtually taken over the South American markets. The South Wales Coalfield as the premier coal exporting area in the UK was hit particularly hard. The owners attempts to reduce costs and wages resulted in numerous industrial disputes particularly the big strikes and lock-outs of 1921 and 1926, this was then followed by the worldwide recessions of the early 1930s and the south Wales coal industry began its long decline.

Vivian was hit particularly hard by the disputes of the 1920s and 1930s and was temporarily closed as a production unit in October 1924. At that time it employed 1,000 men. It did not re-open until February 1929.

The 1921 strike and lock-out were pretty nasty in Abertillery, the miners weren’t too pleased at having their wages slashed by half so they demonstrated in a robust manner, and when this appeared to have little effect other than for the government to impose a state of emergency they threatened to pull out all safety men at the pits which would have meant them flooding. Troops, extra police and civilians were mobilised to protect the owner’s assets; material ones that is, to hell with the living breathing ones. On Tuesday the 14th of April the Royal Navy appeared in town through the sailors of HMS Malaya, 290 of them marched through the town with fixed bayonets in a show of strength, however, they didn’t last long and eight days later they were replaced by another 120 sailors. The strike ended in defeat for the miners at the end of June.

By 1935 Vivian Colliery was working the Black Vein and Meadow Vein seams, employing 70 men working on the surface of the mine and 600 men working underground. The manager was G. Turner. In 1943 it employed 586 men working underground in the Big, Old Coal and Meadow Vein seams and 87 men working at the surface of the mine. The manager was F.A. Hale.

Vivian Colliery was closed by the NCB on the 19th of July 1958 but for several years afterwards its downcast shaft was used to ventilate Six Bells Colliery.

Some Statistics:

- 1889: Output: 33,559 tons.

- 1899: Manpower: 873.

- 1900: Manpower: 929.

- 1901: Manpower: 2,222 with Gray & Tillery.

- 1902: Manpower: 2,329 with Gray & Tillery.

- 1905: Manpower: 2,394 with Gray & Tillery.

- 1909: Manpower: 2,766 with Gray & Tillery.

- 1910: Manpower: 2,980 with Gray & Tillery.

- 1911: Manpower: 2,887 with Gray & Tillery.

- 1915: Manpower: 2,900 with Gray & Tillery.

- 1923: Manpower: 889.

- 1924: Manpower: 734.

- 1930: Manpower: 630.

- 1934: Manpower: 427.

- 1935: Manpower: 670. Output: 200,000 tons.

- 1937: Manpower: 542.

- 1938: Manpower: 615.

- 1940/2: Manpower: 550.

- 1944: Manpower: 660.

- 1945: Manpower: 647.

- 1947: Manpower: 658.

- 1948: Manpower: 605. Output: 150,000 tons.

- 1949: Manpower: 628. Output: 134,000 tons.

- 1950: Manpower: 625.

- 1954: Output: 112,000 tons.

- 1955: Manpower: 503. Output: 114,658 tons.

- 1956: Manpower: 447. Output: 104,486 tons.

- 1957: Manpower: 421. Output: 115,610 tons

SOME OF THE FATALITIES

- 25/3/1899 – Worthy Gunning a haulier, run over by trams.

- 7/1/1896 – Charles Carter, aged 40 years and a collier, collapsed and died of a heart attack. The Jury at the Inquest gave their fees to the widow.

- 31/1/1900 – Alfred Jones, aged 21 years, died under a roof fall.

- 3/8/1906 – A roof fall killed William Owen the overman outright, with William Clothier, timberman, dying two days later.

- 23/12/1911 – Charles Jones died of natural causes. 26/9/1912 – A huge roof fall traps four men and killed Thomas Gauntlett.

- 16/10/1913 – Joseph Price, aged 21 years, killed under a roof fall.

- 28/4/1914 – Albert Jones, aged 37 years, killed under a fall of the roof.

- 18/11/1914 – J.G. Meek, aged 14 years, killed in a haulage incident.

- 4/9/1917 – John Charles Raike died under a roof fall.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page