THE BOTALLACK MINE, CORNWALL by Paul Smith (NMRS member)

A print of the Crowns included in the newspaper article of the disaster, {British Newspaper Archives}. This appears to show the Crowns pre-sinking of the Boscawen shaft. It shows an engine house with smoke coming from its chimney which is situated on the Old Wheal Button Shaft. It illustrates very well the extent of structures on the cliffs at the time

The following extract was taken from one of the many newspapers. It was issued and published in late April 1863 and describes the disaster which took place on 16th April 1863. In which eight men and a boy lost their lives while returning to the surface in a gig (described here as a skip). These were used for man riding in the Boscawen Shaft. A breakage of the haulage chain in use at the time allowed the gig to run out of control down the incline to the bottom with disastrous consequences for all its occupants. I am grateful to the British Newspaper Archives that I found this account and I thank them for this alternative version of this story. I give it here in full:

In one of the wildest parts of Cornwall and only a short distance from Land’s End, lies the famed Botallack tin and copper mine. It has been worked for upwards of a century and during that time various shafts, levels, courses and adits have been worked most profitably in the production of large quantities of tin and copper. Of this mine, we give some descriptive particulars:

The mine has long been notorious for the length and depth of its workings and while it extends downwards to several hundred fathoms, in some parts the roaring of the sea and tumbling of boulders may be heard distinctly by the miner while at work. To obviate the difficulty of raising the ore in a perpendicular shaft and to render the ascent and descent of the miner easier of accomplishment, a diagonal shaft has been constructed through rock and soil and extending for about 400 fathoms. This is known as the Boscawen Shaft. The incline is raised at an angle from the horizontal line of 32 degrees and is about 6 feet high and 8 feet wide throughout its entire length. The nature of the soil has rendered it necessary to make the shaft a little bent in some parts so that the tramway is not exactly straight. This tramway is laid down as far as the 192 fathoms and on it runs what is called by the miners a “skip” – that is made from cast steel or iron, for the bringing the ore to the surface, for carrying materials down to the different levels, and for the conveyance of the labourers to and from their underground toil. This skip is connected by a chain to the workings at the surface and is wound by a “cage” or drum, by steam power as the skip ascends. This cage is under the supervision of a man who is called a “minuter,” who notifies, when the alarm bell is rung, the proper time to stop the engine. This diagonal shaft took some four years in excavating and is a marvellous example of engineering skill, as well as the perseverance in its prosecution by spirited adventurers.

The skip at Botallack is in cast steel weighing about a ton and is 2 feet 6 inches high and will carry eight or nine persons. It has a perfect arrangement of breaks under it, so that if the connecting chain snaps the breaks are self-adjusting, grasping the rail on each side, if the handle is out of the “catch,” by which the skip is immediately stopped on its downward course. This break system is described by the engineers as being very perfect. To secure a careful supervision of the breaks, there is a captain of the skip appointed with each company of miners ascending or descending. The neglect of this, and the breaking of the chain, would be the cause of a serious and fatal accident, as there is nothing to stop the skip from going over the incline with a fearful velocity. The strength of the connecting chain and proper attention to the breaks are two things necessary in the working of this part of the mine’s operations and must be attended to out of consideration for the safety of the miners.

The cause of the accident was the breaking of the chain when the skip containing a party of nine men, was at the 130-fathom level; and as the men were so taken by surprise that the breaks were not applied, the skip ran down the incline at an immense velocity, with a trail of about 3 tons of chain after it. It passed the 160-fathom level, where another party of men were waiting to come up, so swiftly that the bewildered miners could only observe the mere shadow of the carriage, enveloped in a misty cloud. The miners from the hot air being so disturbed, thought the mine was on fire. They immediately went up over the incline on foot to gain the intelligence of their comrades, but it was quickly seen that the lives of the nine persons had been sacrificed. The skip went on its terrific downward course as far as the 190-fathom level, having passed a “sollar” of the woodwork; it reached the bottom of the shaft. It was soon ascertained that all of the miners were killed. When found the bodies were frightfully mangled, cut, bruised, and crushed so much so that the disfigurement rendered it a matter of difficulty for persons to recognise the corpses of their relatives.

The bodies were found in various parts of the shaft: four were found at the bottom, one partly in the skip – the latter of whom was fearfully crushed – and in other parts of the shaft the bodies of others were found, so it is supposed that some of the unfortunate men must have slipped out over the skip, and may have been killed by the lashing of the chain from side to side of the shaft.

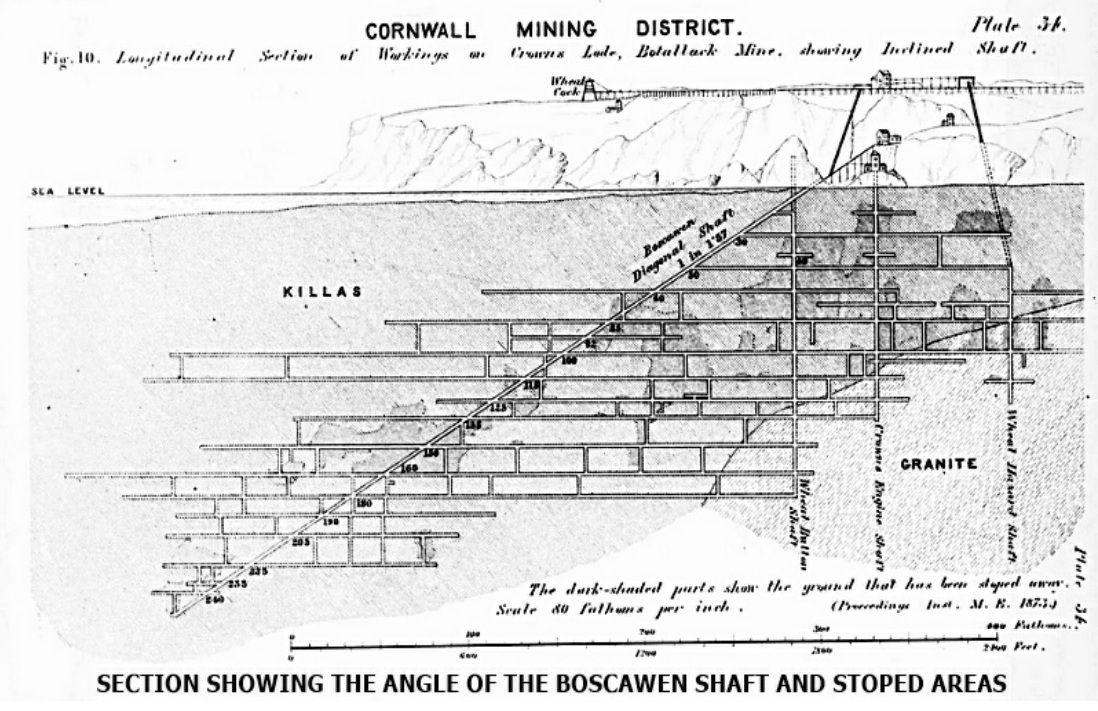

The Crowns section of Botallack mine is situated on the coast near to Botallack village and had for many years been an important part of this large amalgamation of mining setts, it had by the 1850s been developed to a considerable depth and driven quite a distance under the bed of the Atlantic Ocean. This led to major difficulties in working this section efficiently, due to large tramming distances from the main working areas to the landward shafts, ventilation out under the sea, and time taken for men to reach the rich areas of ore, added to this is the fatigue brought on by climbing ladder ways for over 1000 feet, reducing the amount of work that the miners could do in their working day.

The Crowns was the main copper producing section of the mine, the copper being found in lodes in the killas rock overlying the granite (killas being a clay slate rock) the granite coming to the surface inland provided the tin producing lodes at Botallack.

WHY A DIAGONAL SHAFT?

The copper mineralisation hereabouts, that is the ore shoots, are found ever deeper the further out from the coast they are worked. The reason for this is that the junction between the killas and granite is not vertical, but has an average angle of about 60 degrees to the vertical with the junction of the killas and granite being thrown ever deeper out to seawards. The ore-shoots tend to follow the junction (all be it a shallower angle than the junction itself) being thrown further and further out to sea with depth. By the later 1850s, the mine was already 180 fathoms below adit, the end at this level being already 325 fathoms North of Wheal Button Shaft (the main winding shaft of the Crowns section at the time). This end had yet to reach paying ground, although a winze below this level was in copper ore. Now to develop the mine further Button Shaft would need to be sunk to the 195-fathom level and the level driven to meet the ore shoot all in the non-paying ground and at great expense both in time and cost.

The copper mineralisation hereabouts, that is the ore shoots, are found ever deeper the further out from the coast they are worked. The reason for this is that the junction between the killas and granite is not vertical, but has an average angle of about 60 degrees to the vertical with the junction of the killas and granite being thrown ever deeper out to seawards. The ore-shoots tend to follow the junction (all be it a shallower angle than the junction itself) being thrown further and further out to sea with depth. By the later 1850s, the mine was already 180 fathoms below adit, the end at this level being already 325 fathoms North of Wheal Button Shaft (the main winding shaft of the Crowns section at the time). This end had yet to reach paying ground, although a winze below this level was in copper ore. Now to develop the mine further Button Shaft would need to be sunk to the 195-fathom level and the level driven to meet the ore shoot all in the non-paying ground and at great expense both in time and cost.

The suggestion therefore in 1858 was to sink an incline shaft to reach the present 180-fathom level end at a distance of about 360 fathoms from the shore, this was to be known as the Boscawen Diagonal Shaft. The angle chosen at which to sink the shaft was 32.5 degrees to the horizontal, this angle being chosen because of the ore shoots being thrown further away from the granite killas junction as the depth increased. It was reckoned that an incline could be sunk at less expense than sinking the sump, and certainly a lot less than driving another long level, all to be repeated as the mine went ever deeper, whereas the diagonal shaft could just be extended at the same angle to follow the ore shoots and would be of considerable value to the mine in future. It would also help to ventilate the mine in depth out under the ocean and could carry men close to their place of work, meaning the men arrived fresh and ready for work In April 1858, the appearance of the rich copper ore in the winzes below the 180 was making the sinking of the shaft with all speed imperative and work had already started from the surface, Wheal Button shaft was reached by June of that year (this shaft being on the line of the new incline). The shaft was at this time sinking and rising at the 20-fathom level rising over the 33, driving the 50 and rising over the back of the 65-fathom level. By August the shaft was being worked on by 16 men and 6 boys at various points to speed the progress.

The October report shows even more men working in the shaft with 20 men and 13 boys employed in sinking Boscawen Shaft alone, this showing the importance placed on this project by the management of the mine. In December 1858, 160 fathoms had been opened up in the shaft and all was progressing well, this was increased to 225 fathoms by the next April. The only place where work was being delayed at this time was about mid-depth, where heavy timbers were needed for support. October 1859 saw Boscawen Shaft communicated from the surface to 8 fathoms below the 150-fathom level and railroad being laid in the completed section of the shaft. Men were now employed in squaring and securing sections of the shaft, with the shaft reaching the then depth of the mine (180 fathoms) by February 1860, by April 300 fathoms of the shaft was open and the railroad laid to the 50-fathom level. Warrington-Smyth (Duchy of Cornwall inspector of mines) stated that the incline shaft was almost complete and that the section which looked dangerous (mentioned above) had been secured with expensive American and Baltic timber baulks 16 inches square. The shaft continued to be sunk below the then bottom of the mine and had reached 8 fathoms below the 180 fathom level with the Crowns lode still not cut through. At this point there is a gap in reports on the mine, which restart in October 1861, by this time the engine house for the draught engine and boiler house was complete, the engine erected and the boiler fitted.

There is a comment that difficulties of position retarded progress, anyone who has visited the Crowns will not be surprised by this comment. This engine was reputed to have come from Wheal Button (where it stood near the bottom of the cliff to draw from that shaft) I can now confirm that as true, having found a newspaper report from this time describing the hauling of the boiler halfway up the cliff and then lowering back down to its new position at Pearce’s Whim (the name given to the engine in its new position). The engine was moved in a similar fashion.

The report of January to March quarter of 1862 is a little special and states that the Boscawen Diagonal Shaft is working to the bottom of the mine to our entire satisfaction. The shaft had cut the Crowns lode at the 190-fathom level, it being 2 feet wide here and worth £20 per fathom for copper. This completion of Boscawen Shaft ended a number of years investment at Botallack with £10,000 being spent on this shaft, a new steam stamping engine and new tin dressing floors near this stamps engine.

The Boscawen Diagonal Shaft was driven Northwards at an angle of 32.5 degrees from the horizontal, it started a little above sea level on the cliff and reached an eventual depth of 250 fathoms below adit and about two-thirds of a mile out under the sea. At the time of opening, it had reached the 190-fathom level but only worked to the 180 level. Between the engine house and the mouth of the shaft, the rails ran on a huge wooden trestle across the cliff face. Ore was raised in a skip which ran on rails the entire length of the shaft, there was a landing place just below the engine house, from here the ore was transshipped to another skip, which was drawn up the cliff face on a further trestle by an engine on the clifftop to the copper dressing floors which stood atop the cliffs above Pearce’s Whim. The diagonal shaft was also used for lowering materials needed in the mine and for man riding in and out of the mine, this facility caused problems for the mine as it made it possible for tourists to easily visit the mine, over the next few years, with this taking up valuable winding time.

There was also a terrible accident when winding men, just over a year after the shaft was opened, when a winding chain broke, plummeting 8 men and a boy to their deaths, that will be dealt with elsewhere in this account. It seems that the shaft was not the great success hoped for, the ores thinning out with greater depth and not being worth continuing to work below the 250-fathom level. This section of the mine was abandoned in early 1874, along with it the use of this incredible shaft and the fantastic engineering feat to wind from it. So was it worth it then, probably not, it only worked for 10 years, perhaps being another of those white elephants that seem to happen quite regularly in mining.

It did however leave us with one of the most spectacular pieces of mining scenery in the world, for us all to visit and see. The engine house is perched spectacularly on a cliff edge, the shaft mouth with a huge boulder in its entrance is still visible across a chasm that once had the wooden trestle built across it to carry the carriage as it emerged from the shaft. It is so impressive what miners of this era managed to construct, drive and sink, with all of the underground work done by candlelight, hand drilling, gun powder blasting etc.

BOSCAWEN SHAFT IN OPERATION

The shaft itself had only one set of rails running in it, laid at a gauge of two feet seven and a half-inch, due to its small size, this ran from the engine house over a trestle to the mouth of the shaft (itself about 30 ft above sea level) and from there to the bottom of the shaft at a 32.5-degree incline. The shaft was relatively small in dimension varying between 5 and 12 feet in width with a height of about 6 feet.

Two carriages were built to work on this incline, a skip for the carriage of ore and materials, and a separate gig designed for man riding, both were designed by Captain Rowe the mine’s engineer; Holman and Sons of St. Just manufacturing them both. Haulage in the shaft at the beginning of use was by a chain, this being graduated in size over its length to allow for the greater strain on the upper portion as the weight increased with paying out of the chain, the first 100 fathoms being 5/8-inch best charcoal iron, the second 100 fathoms being 9/16-inch, the remaining 200 fathoms being ½-inch iron. The mineral carrying gig weighed about 8 cwt and carried a load of 16 cwt.

The man carrying gig weighed about 14 cwt empty and was designed to carry 8 men (often one extra boy was carried, making a total load of nine persons), seats were arranged in tiers to allow for the low roof in the shaft, 2 men riding side by side in each tier. The chain was attached to the underside of this carriage by an ingenious system of levers and spring, which if the chain should break would apply claws to either side of the narrow part of the rails which the carriage ran on, to arrest any runaway which might occur (unfortunately this failed to prevent the disaster in 1863). The operation of this man carrying gig along with a description of the accident will be described in the next newsletter. This will also include a description of the shaft as a tourist attraction and some of the famous persons who visited the mine via this amazing shaft.

THE MAN CARRYING GIG AS DESIGNED AND BUILT

As mentioned previously the man carrying gig or carriage was designed to run on the rails laid in the Boscawen Diagonal Shaft which was sunk at an angle of 32.5 degrees to the horizontal. It was hoisted by a chain wound onto a drum of a Cornish Beam Whim (winding engine), the chain was graduated in size over its length to allow for the increase in weight of the chain over the incline. The chain that was connected to the gig was ½ inch best charcoal iron and was 200 fathoms in length, the next 100 fathoms being 9/16 iron and the final 100 fathoms which was connected to the winding drum 5/8 best charcoal iron. The gig weighed 14 cwt when empty and carried 8 men, although often an extra passenger was carried when a boy needed a ride. The carriage was 6 ft 10 inches in length and 2 ft 5 inches wide by 20 inches deep and had 4 rows of seats. Sitting two persons to a seat, the seats were arranged in tiers to allow for the low height of the incline shaft. The gauge of the tramway in the shaft being 31 ½ inches.

A safety mechanism, which applied the brakes was fitted to the carriage and worked in the following manner: On the underside of the carriage, a large spring was attached to the carriage with the other end of the spring being connected to a bar, which was free to travel in a groove. Connected to this bar by a series of linkages were two toothed cams aligned with the narrow part of the side of the rails on the incline. While ever the spring was kept in tension the cams were kept clear of the rails, if no tension was applied to the spring the cams would jam on to the rails causing the gig to stop. Tension was applied to the spring by the weight of the gig, this tension was supplied by the fact that the opposite end of the bar (to which the cams were connected) was connected to the winding chain used to draw the car up the incline. This type of safety system however could not be used on descents as the lower tension on the spring (especially if the gig was empty) caused the brakes to be applied. To get around this problem another system of levers was connected to a manually operated brake lever on the side of the gig. This lever when applied kept the spring in tension stopping the brakes from acting on the rails. For downward journeys when no one was travelling in the gig a catch was supplied for this brake lever to keep it in the none braking position. When men were travelling in either direction this brake lever had to be attended by a brakeman, who held it in a position as to keep the brakes off and out of the catch. If anything untoward happened such as a chain breakage it was the brakeman’s responsibility to let go of the brake lever causing the gig to stop and be held in its position on the incline. The job of a brakeman was a very responsible one and men received considerable training in the operation and use of the brakes on the carriage. This system worked well and was regularly tested, even after the accident the damaged carriage was put back onto the rails and the brakes were found to be still in working order.

THE TERRIBLE ACCIDENT ON 18th APRIL 1863

Theoretically, the braking was automatic if the lever was out of the catch and a chain breakage occurred while ascending the shaft the brakes should be applied automatically, but a brakeman was still present at all times.. Initially, Boscawen shaft communicated between the landing place at the surface and two landings in the shaft (the 135 & 165-fathom levels) from these points the men climbed the ladders to and from their places of work. The system worked well and was liked by the miners as it saved a lot of ladder climbing to and from the places of work. Unfortunately, a tragic accident occurred when the mine was still in its infancy, a description of this follows.

THE BOSCAWEN SHAFT GIG DISASTER

This accident happened on 18th April 1863 at approximately 2 pm when a group of miners were returning to the surface after a day’s work. One group of miners had already ascended and about 18 others were waiting at the 165-fathom level for their turn to ascend. A normal load consisted of 8 men however it was decided to carry an extra passenger a boy in order to split the load between two trips. Shortly after the gig had started its ascent the men remaining at the 165-fathom level heard a sound like a gunshot and something flew past them down the shaft, the gig was travelling so quickly they only saw a few sparks. In shock, the men descended the shaft to the bottom to find out what had happened to their comrades. Unfortunately, it was to no avail as all eight men and the boy had perished some with horrific injuries. The boy was found about 3-fathom above with a fractured skull, discovered there by his own brother who had been first to rush down the shaft. Another man was found in the shaft just below the boy with his chest crushed and his ribs broken. A father and son were found under the carriage lifeless and one other still inside the carriage, which had been stopped by timber bracing 8ft from the bottom of the shaft. The rest of the doomed men were found lying upon one another at the bottom of the shaft. It is presumed that none had survived the impact, with some of the bodies being terribly mutilated. As a news report put it, “Each one was injur’d fearfully, Bruis’d, broken, smash’d and dead. A sickening spectacle as some had lost parts of their heads”

The acting brakeman on that fateful day was Thomas Wall, a witness at the inquest stated, “ I have a son lying dead from the accident if I had been in the gig or Thomas Wall had the lever in his hand my mind tells me my son would be alive now. I feel so much confidence in the gig that I am sure the handle was in the loop”.

So why had the accident occurred with all the safety equipment on the gig? The chain had broken at a 9/16-inch link about 70 fathoms above the 165-fathom level. The link appeared to have been weakened by “surging” (sudden slipping when chains are on top of each other on the drum). The brake was found to be still in working order when tested later by its designer. However, no marks made by the safety claws were found anywhere on the rails when an inspection was made. If the handle had been in the brakeman’s hand and he had released it the claws would have arrested the descent, but if the brake handle was in the catch it would not operate the cams and the carriage would be free to run away down the incline. Even if the brake handle was in the catch the brakeman should have been able to operate it. However, it was thought he may have become paralysed with fear or was not in a good position to operate the lever. The gig hurtled down the incline with ever increasing velocity until it reached the bottom of the shaft (possibly reaching 100 mph). Another train of thought is that the drag of the chain left behind the gig may have been enough to stop the brake from operating as designed. However, at the inquest it was concluded that had the acting brakeman exercised full care in the working of the brake handle the accident would have not occurred.

Those killed in this tragic accident were: John Chappel, John Chappel Jr, Thomas Wall, (acting brakeman), Richard Wall (his son), Michael Nicholas, John Eddy, Peter Eddy, (his cousin), Thomas Nankervis and Richard William Nankervis, aged 12.

BOTALLACK AS A VISITOR ATTRACTION

Most of us know Botallack and the Crowns, it must be one of the most photographed old mines in the country if not the world, with its spectacular cliffside setting it is a joy to photograph in any of season of the year. What is a little more surprising is this mine was a tourist attraction when being worked, visits of course happened well before Boscawen Shaft was sunk but the new shaft drew visitors like a magnet. Now a person could visit the very depths of a Cornish mine without the trouble of climbing slippery unsafe ladders. This did however bring its problems and it was a great burden to the working of this section of the mine. With the rising numbers of visitors accommodating people on a trip and the appointing of an underground agent (mine captain) along with the provision of a change of clothes and the use of the gig in Boscawen shaft were all a drain on the mine. Limits had to be placed on numbers in some way, it was decided therefore to make a charge for the privilege of going underground via the Diagonal shaft. The way all this was done was to ask for a donation of half-a-guinea from everyone who descended Boscawen shaft into the mine. The monies collected in this manner were set aside as a fund to help the widowed and maimed family’s connected with Botallack Mine. A visitors book was kept and by 1871 over £300 pounds had been collected in this way, the last entries into this book are dated 1874 not long before the Crowns section was abandoned.

The best-known visitors to Boscawen shaft were of course Prince Edward and is wife Princess Alexandria. Known in Cornwall as the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall (Prince and Princess of Wales) later to become King Edward VII and Princess Alexandria, they visited the mine in 1865 not that long after the disaster had happened. They descended in the same gig that had been involved in the accident via the same Boscawen Shaft and broke some copper ore to take as souvenirs. By this time wire rope had replaced the chain and no doubt a very responsible brakeman had been appointed for the descent and ascent. This visit of course had the effect of increasing the mines popularity as a visitor attraction over the next few years.

R M Ballantyne also visited in 1868 and must have based much of his book Deep Down on is experiences that day. It is some of the lesser known visits which most interest me, they include a visit by Prince Arthur, Edward VII’s younger brother, also an early visitor to the shaft was Lady Falmouth. Lady Falmouth along with the Hon. Miss Boscawen visited Botallack and descended Boscawen Diagonal shaft sometime earlier in the same month as the accident occurred, they travelled to the 180-fathom level to inspect the mine this is mentioned in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, 15th April 1863. This meant that they travelled in the same gig, drawn by the same chain about a week prior to the terrible accident in the shaft in which 9 lives were lost.

The other report I have found which I have not seen published in any other information regarding the mine is the visit by Prince Arthur (Queen Victoria’s youngest son) on the 15th May 1862. This can be found in several papers on the British Newspaper Archives website part of which is transcribed here out of interest. The Prince had wanted to go underground at Botallack, to follow in the footsteps of his father Prince Albert who had visited the mine and descended the ladder ways earlier in the century.

The following is my transcription of the event:

The Prince had heard his lamented father speak of the submarine and underground wonders of Botallack, and had resolved to inspect them for himself. The completion of the diagonal shaft and increased ease and security with which the 180-fathom level may be now reached, came to the aid of his Royal Highness, his tutors resolved to accompany him. After partaking of the hospitality which characterises Botallack the prince, Major Elphinstone and the Rev. W. Jolley exchanged their broadcloth for the warm but course flannel clothes of the miner. A photograph of the Prince in his copper-stained apparel, hard miners hat, and candles at his button-hole would have amused the Court on a future day, but no artist was at hand. Mr. T. S. Bolitho saw his Royal Highness safe to the skip of the shaft, in which a precious freight was deposited, and, accompanied by Mr S. H. James Jr, the captains of the mine, Capt. Austen, and Mr Glyn Bolitho, the strangers descended to the 180-fathom level by tramway, and penetrated and descended the mine at other points. His Royal Highness himself broke off three or four specimens of ore and will preserve these as mementoes of his underground trip. This was three years before his brother descended the same shaft, and less than a year before the terrible accident in the shaft. The chain in use then would be nearly new as the shaft had not been open long when this trip took place.

Many other celebrities of the day descended this shaft and visited what at the time was one of the wonders of West Cornwall. These included Russian Princes, Dukes, Duchesses and many other VIPS. Botallack and the Crowns at this time must have been one of the must-see attractions of Cornwall even for those who did not venture underground.

It is with great thanks to Cyril Noall and his wonderful book, Botallack that this has been able to be written, with lots of additions from my own research in the British Newspaper Archives and elsewhere. Diagrams and photographs, Including the wonderful pre- Boscawen shaft print of the Crowns, is used courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive. I have also called upon knowledge gleaned from many friends interested in mining over many years. Including Peter Joseph, both from his publications and personal contact on walks he has led over the years.

I would also like to mention my great friend Kenneth Brown, who passed on much knowledge about the engine at the mine and its operation over the years. I would thus like to dedicate all three pieces written on Botallack to the late Kenneth Brown it his inspiration which has made me delve much deeper into the archives and write a little about the knowledge gained in these pages.

Paul Smith. (NMRS Member)

Return to previous page