My father had said to me, “If tha wants, I’ll get thee a job down’t pit”.

My initial reaction was to cast it off out of hand. The mere thought of going down a hole in the ground and working underground was totally awesome and more than a little frightening.

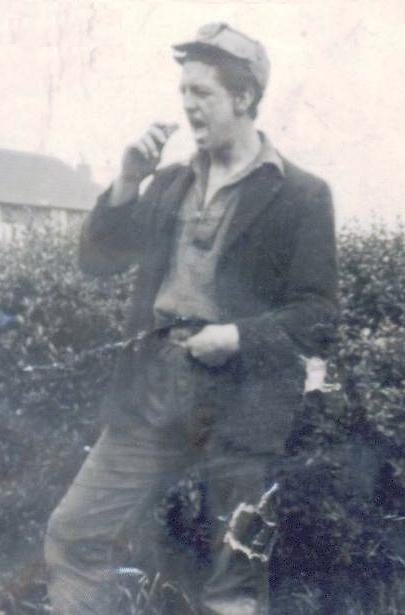

Jack Gale 1953

My name is Jack Gale and being just Fifteen and a half years was not long out of school. The year was 1951 and I was lucky in the fact that my generation still enjoyed full employment. It wasn’t just a case of which job to take after leaving school, but more the fact of how much wages one received at the end of the week.

Not having the advantages of a grammar education, I had left school with only a basic level of knowledge. In all ordinary senses my life was mapped out, I would leave school, get a job, meet a future wife, save up to get married, get a house, have kids, grow old and then retire. Probably a not too long a retirement at that; very old ex-pit men were few and far between. But of course I thought of nothing much further ahead than the end of the working week when I got paid and what I would spend my money on.

I was born into a coal mining family. My father, like his father had, worked down the same pit, Middleton Broom Colliery, in South Leeds, Yorkshire. All my young life, it seemed, my father had said, “No son of mine’s going down’t pit” And now here he was offering to get me a job down that self same mine. It was sometime after however, that I realised my father had an ulterior motive behind his suggestion.

Having had some success in schoolboy boxing, he was thinking bigger things for me in the amateur and then the professional ring. I, on my part, had no thought of boxing as a future. Although I was always afraid when actually entering the ring, as soon as the bell went I would enjoy boxing. The problem was that I hated the time spent training, which was necessary if anyone was to succeed in that or any sport. Basically I was very lazy when doing something that was less than exiting or interesting.

My dad had reasoned that if his son spent less time at work he would have more time to rest, and be refreshed, before going training in the evening. He realised, having been a Semi professional boxer in his day, perhaps his son could aspire to the greatness he had never achieved. He reckoned that sport was the only way his son would be able to get out of the normal working class routine and actually make something of himself.

In the days that followed I slowly came to the realisation that a move from my present job as a labourer, for a tiled fireplace fixing company, was long overdue. I had been working for my Uncle, who owned the company, for all of three months. The work was boring and the pay was relatively small, two pounds and ten Shillings. The hours seemed long, forty four hours a week. In comparison to the colliery’s six pound odd, for thirty seven and a half hours work.

The more I thought of a mining job the more I realised that there were more pros than cons. When I asked finally of my father, “Exactly how much are the wages at the pit would I get” he must have done some research, for I received the reply. “six pounds seven and six, when tha’s done thee training” This sounded an enormous sum to me but the clincher was, “An tha’ll not have to go in ‘t’ Army.”

National Service was in operation at the time, all able bodied youths, unless they were a deferred apprentice, had to enter one of the three military services on attaining the age of eighteen, for a period of two years. Coal mining was an exempt occupation, well, underground working was. The ones that entered mining to evade the services were nicknamed ‘Bevin Boys’ after Earnest Bevin who saw an act through parliament.

That last remark of not going in the army, was the clincher for me, I had never been away from home for any length of time in the past. When I had thought about it, the Army seemed an unattractive prospect.

“Will you ask about a job for me then Da?” I asked.

“I’ll see Benny Wilkie in the morning,” replied dad. Benjamin Wilkinson was the Colliery Safety and Training Officer. True to his word father returned home the next day with the news that he’d arranged for me to see the training officer on the following Saturday morning.

“What makes you want to work within the coal mining industry, Jack?” was the interview opening question from Ben Wilkie.

Being unused to interviews or answering technical questions, I had to study for a moment, before replying “Cos there’s more money in it.” It was the only answer I could think of.

“That’s true Jack, but there is also danger, dirt and hard work as well. And the good money only comes when you actually work underground. Surface work is no better or worse paid than most jobs.”

“Oh! Of course I want to work underground that’s why I’m here,” I said. I hadn’t really thought that once coal was brought to the surface it had to be processed. I think that I had expected to go straight down the pit.

Ben W. went on, “You will start work on the surface in the screens for a few months. Then if you are acceptable to us and you are happy to remain with us, then we will send you for sixteen weeks training, prior to your start underground. You will be trained underground at a training pit and at the surface training college at Wakefield; eight alternate weeks at each. Do you understand all that and do you have you any questions for me?”

“Yes when can I start?”

“Okay then Jack, you look big enough to work here and coming from a mining family you should have an insight to what pit work entails, can you start on Monday?”

“Yes”, I responded.

“OK Monday morning at six, report to the Screens. See Joe Garvey there, he’s in charge, he’ll show you what to do”

“Where are the screens?” I enquired.

Pointing out of his office window Bennie W. replied, “That tall building next to the headgear, see you on Monday”. And with that the interview was obviously over.

It was some time later that I realised that to do what was right, I should give at least a weeks notice to my present employer. But on thinking, I owed them nowt nor did they owe me. My mam would phone my uncle and put it right, which she did.

Go to Next Chapter or Index