EDGE GREEN. Garswood Hall No.9 Ashton-in-Makerfield, Lancashire. 12th. November, 1932.

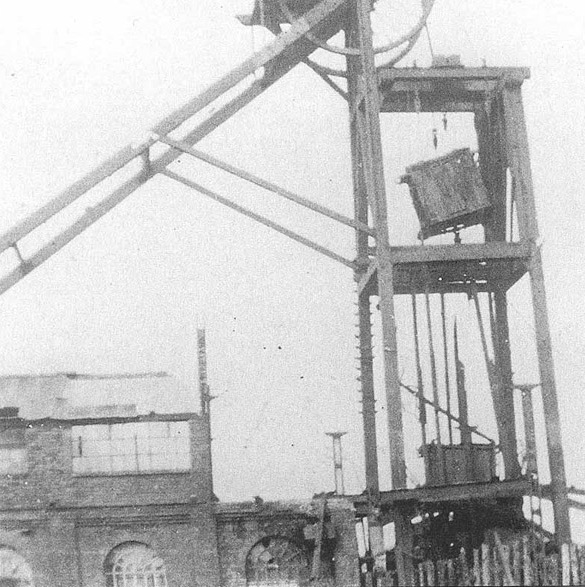

The colliery was abandoned after the explosion and the shaft filled, but even as this was going on it exploded again, injuring no one but throwing the cage into the headgear.

The Garswood Hall No. 9 Colliery was one of a group of Collieries owned by the Garswood Hall Collieries Company Limited, of which Mr. James H. Edmondson was the Managing Director. Mr. William Sword was the Consulting Engineer and Mr. H.J. Whitehead, the Agent. The Colliery was situated off Edge Green Lane in Ashton-in-Makerfield, Lancashire and was also known as the Edge Green Colliery. Mr. J. Latham was the Manager and Mr. Peter Bullough the undermanager of the No.9 Colliery, which had three shafts, the No.9, the downcast and coal-drawing shaft, the No.2, which was the upcast shaft and the No.3, which was close to the No.2, but at the time of the explosion was not in use.

The seams that were worked at the Colliery were the Ravin and the Orrell Four Foot which was called the Arley mine. The Arley was reached from the Ravin by two tunnels driven through an upthrow fault to the east with a throw of some 80 to 90 yards. The strata dip to the southeast at the rate of 1 in 5½. The working day was divided into three shifts; day, afternoon, and night with about two hundred and two people being employed on the day shift, one hundred and five on the afternoon shift, and one hundred and sixteen on the night shift. Coal was got on the day and the night shifts and wound during the day and afternoon shifts. The average daily output was about 800 tons. The repair work was done on the afternoon shift. Supervision of the workforce underground was exercised occasionally by the Agent and on a daily basis by the manager and the undermanager. They had a staff of eleven firemen, four on the day shift, three on the afternoon shift, and four on the night shift. On the day and night shifts, there was a fireman in each of these districts. On the afternoon shift, one fireman supervised the No.5 Brow and No.2 Brow districts, but there was no work in the No.2 Brow district during that shift. The Colliery did not employ any overmen or other officials between the undermanager and the firemen. An inspection was made by each fireman towards the end of his shift and this inspection constituted the inspection within two hours of the commencement of work in the succeeding shift. Reports of these inspections were duly entered in the prescribed report book kept in the office at the pit brow.

The workings are divided into four districts, three of which were on the North Side, No.5 Brow, and No.2 Brow” all of which were in the Ravin seam and the other district was the “Orrell Four Foot”, in the seam known by that name as well as by the name Arley. The station for all the districts was at the bottom of the No.9 pit and this was where the Report books were kept.

The ventilation of the mine was by means of a “Walker” fan situated near the top of the No.2 shaft, which caused a total quantity of 28,500 cubic feet of air per minute to pass through the workings. Of this total quantity, 10,500 cubic feet ventilated the “North Side” district, and the remainder passed along the South Level to ventilate the Orrell Four Foot, the No.5 Brow and No.2 Brow districts. The North Side was not affected by the explosion.

Travelling inbye along the South Level, the No.2 Brow was reached first, then the No.5 Brow and finally the South Brow, which lead directly into the workings in the Orrell Four Foot Seam, beyond the upthrow fault already mentioned. On No. 2 Brow, between Nos.2 and 3 Levels, there were two wooden doors to prevent the air from passing down that brow. The air current, less the amount that leaked through these doors, continued along the South Level to the No.5 Brow where 6,800 cubic feet per minute turned down that brow, leaving the remainder to pass on and down the South Brow into the Orrell Four Foot. This split of 6,800 cubic feet, travelled down No.5 Brow as far as No.10 Level where its progress down brow was barred by two wooden doors placed across the brow. One was just above the No.11 Level and the other just above the No.12 Level. Entrance to the No.11 Level was blocked by a brick stopping, but the entrance to the No.10. Level was not blocked. This split of fresh air returned into that level and was guided along it to No.8 Brow by brick stoppings built across No.6 and No.7 Brows. Following that part of the air current which, having passed beyond the top of No.5 Brow turned down the South Brow, it was found that, after being coursed around the workings in the Orrell Four Foot seam, it returned upbrow and eventually arrived at the No.5 Brow district where, at the junction of the No.8 Brow with No.10 Level, it rejoined the split which has reached this point by way of the No.5 Brow and the No.10 Level. The quantity of air in the last-mentioned split, measured on the 25th of October was 6,060 cubic feet per minute. There was a current of air slightly over 12,000 cubic feet per minute which, after ventilating the workings in the No.5 Brow district, passed on to, and around, the workings in the No.2 Brow district, and then, after joining the return air from the North district, by way of a long main return airway to the upcast shaft which was the No.2 shaft.

This scheme of ventilation was in operation at the date of the explosion, but before the 5th September, the two doors in the No.5 Brow had been near the top of that brow and no fresh air, other than that which leaked through the doors, was passing down the brow. It was a scheme which appeared to have been sufficient so long as the working of the Ravin Seam was confined to the getting of coal in “stret” places only, but when the boundary had been reached and the taking out of the pillars, formed by the driving of the “stret” places, became necessary, then it’s sufficiency became doubtful, especially as the goaf to be laid down was to the dip of the district.

The first sign of this, so far as could be ascertained from the firemen’s report books or any of the witnesses at the inquiry, was the detection of firedamp, towards the end of the shift on 1st. September, in the working place of a collier, William Edwards. According to the evidence given by Mr. Edwards, he had just found this firedamp when the fireman, William Marsh, came into the place and Marsh, after making a test, withdrew him from it.

In his report book in reference to the inspection made by Marsh, he reported, under the heading “Noxious or Inflammable gases” – “None, except a three percent cap in W. Edwards’ place in No.8 splitting. Place fenced off”. A similar report was made daily by each of the three firemen inspecting in the No.5 Brow district until the report at the end of the morning shift on 9th. September William Marsh reported: “Edwards’ place clear, all fences removed”. A second sign of doubt as to the sufficiency of the ventilation scheme occurred in the report of the inspection made on the same day, the 1st. September, of the No.2 Brow district, between the hours of 8 and 10.30 p.m. by the fireman of the district, Frank Clough. That report in reference to the finding of noxious or inflammable gases read: “A show of 2 percent. Cap of gas coming from the No. 5 panel brow.”

On the 1st. September, the manager was on holiday. He returned to work on the 5th September and after consulting with the agent and the undermanager, he set about trying to try to improve the ventilation on the No.5 Brow district. As things were, he found his greatest difficulty was to concentrate the ventilating current on the edge of the goaf and the working places and to keep it from escaping through the stret places driven in the first working. His first step was to take away the doors situated across No.5 Brow near the top, and to hang brattice sheets across that brow just below the entrance to No.10 Level, so fresh air was free to go down the No.5 Brow and into the panel side of the No.5 district by way of the No.10 Level, where it joined the air current which had been round the workings in the Orrell Four Foot.

The brattice sheets below the entrance to No.10 Level, however, allowed too much of the fresh air coming down the No.5 Brow to escape directly down that brow, so two wooden doors were erected and the brattice sheets were allowed to remain. Brick stoppings were erected in Nos.6 and 7 Brows between Nos.10 and 11 Levels and across the entrance to No.11 Level off No.5 Brow.

On the 8th September, the manager made a test with a McLuckie apparatus to the return end of the No.5 Brow district to determine the percentage of firedamp in the general body of the air at that point and found it to be 1.35%, This he considered to be an exceptionally high percentage, so he returned to the same district the following day and on making a similar test he found that the percentage had risen to 1.5. He measured the quantity of air passing down the panel brow intake and found it to be 10,000 cubic feet. He also made a similar measurement either on No.13 Level or in the working place below, he was not quite sure which, between Nos.6 and 7 Brows, and found the quantity of air passing to be 8,800 cubic feet per minute and to be carrying 1.2 percent of firedamp.

Efforts to keep the air on the working places were continued and, on the 22nd. September a door in a brick wall stopping was erected on No.12 Level about 18 yards on the inbye side of No.7 brow but two days later, the Manager found, so far as he could remember, because he had kept no record, 0.3 or 0.4 percent of firedamp in the general body of the air at the intake end of the district, rising to 1.2 percent at the return end. He stopped all shotfiring in the district. On the 24th of September when he prohibited all shot firing in the district but, by the 29th. September, he considered the ventilation to be so improved that he felt justified in allowing the firing of the shots to be resumed.

The extracts from the firemen’s reports seem that no report of firedamp having been found between the 9th and the 22nd September, its appearance as reported by Storer, on the afternoon of the later day, by Lowe in the succeeding shift, and then again by Storer on the 23rd September, had been the cause of shotfiring being prohibited. But Mr. Whitehead, the Agent, who visited the No.5 Brow district on the 26th September, said that this was not the case and explained that shotfiring was stopped because of the finding of “a slight percentage, 1.2 per cent, of firedamp in the general body of the air”. He said he was concerned about the ventilation of the district, not because of the 1.2 per cent firedamp in the general body of the air, but because of the two percent firedamp reported by the firemen in the No.6 Brow even though it was also reported as being “made dilute”.

This explanation was difficult to understand if the two percent of firedamp reported by the firemen was, in fact, “diluted as made”. These words, however, have been understood in mining parlance or, having been used once, were repeated time after time in a parrot-like fashion. The fireman Marsh, said the indication on his lamp of the firedamp coming from Nos.7 and 6 Brows ceased only when, travelling outbye along No.13 Level, he had nearly reached the No. 5 Brow. That there was no gas in the air all the way along No.13 Level from No.7 Brow to the end of No.6 Brow, and that this gas was coming up No.7 Brow continuously and was kept off the men working in the ribbing to the left of the at brow by a brattice sheet stretched from the landing place to the face.

The Inspector found it difficult not to doubt whether the whole of the facts in connexion with the occurrence of firedamp in the No.5 Brow district were divulged to the Inquiry, especially having regard to the evidence given on the last day the Inquiry by a miner, Francis Smith. Smith said that three weeks before the explosion when packing rubbish behind a stopping in the brow, to the dip between Nos.5 and 6 brows, he was “gassed” and had to be taken out of the mine. He saw of work a fortnight, had to have a doctor and was paid compensation.

Mr. Whitehead, during his inspection of the district on the 26th September, found that the ventilation was rather sluggish due to leakage along No. 12 Level, and he instructed the manager to improve the brattice sheets on that level and to hang more. These sheets were not in a neglected condition, but they were being lifted by the haulage rope, and the wood door on the inbye side of the No.7 Brow could not be kept shut because of the running of that rope. This door was removed from its frame and replaced by a brattice sheet.

During October the general state of the ventilation appeared to have been improved except that, as has been seen, two percent of firedamp, “diluted as made”, was continually reported until 10.30 p.m. on the 24th in No.6 brow and from that date onwards in the No.7 Brow, the same percentage being observed and the same remark. “diluted as made”, was recorded. On the afternoon shift fireman, Storer, reported on his inspection made between the hours of 8.30 p.m. and 10.15 p.m. on the 7th September, recorded that he had found no gas in No.3 Engine Brow which was off No.12 level and that it was fenced off and was being attended to. In evidence to the inquiry, he explained that he found firedamp at 3.45 p.m. about half-way down the brow below the No.12 Level and he put a fence across the brow and then going down the next brow outbye, No.9 Brow, he also found firedamp halfway along the right-hand ribbing and he put up a fence there too. He explained that this firedamp had accumulated because a brattice sheet across the No.12 Level at the top of the No. 9 Brow had been disarrayed. He repaired this brattice sheet and went away to attend to his duties. He returned at 10.15 p.m. when he found the firedamp had been cleared as far as the bottom of No.3 Engine Brow. The next report in reference to this accumulation of firedamp was made by the nightshift fireman, Mr. Lowe, on the 8th November, when he reported – “No.3 Engine Brow and No.12 Level found clear at 5 a.m.”

There was a discrepancy in these reports. Storer reported he found gas in the No.3 Engine Brow off No. 12 Level and Lowe reported No.3 Engine Brow and No.12 Level found clear at 5 a.m. From the last report, it could be thought that Lowe had found firedamp on No.12 Level. It could have been that he had not read Storer’s report with sufficient care and, when writing his own, he had in his mind that Storer had in fact reported that he had found firedamp on No.12 Level. The truth would never be known as Lowe was killed in the explosion. The main point of these reports lay in the fact when the dayshift fireman, Marsh, left the district towards the end of the morning shift on 7th. November and met Storer at the pit bottom between 2.30 and 2.35 p.m., he knew nothing of any firedamp in the No.3 Engine Brow and yet at 3.45 p.m. Storer found firedamp half-way up that brow, and according to his evidence, the disarrangement of a brattice sheet. At 5 o’clock on the following morning, Lowe found that the accumulation had dispersed. This showed just how quickly firedamp accumulated following the disarrangement of the brattice even at the intake end of a district.

Mr. Latham became manager of the colliery in May 1931 and it was on record that he did not consider the scheme of ventilating the Orrell Four Foot, the No.5 Brow and the No.2 Brow Districts, a good one. He planned to have two separate splits of air, one for the Orrell Four Foot and the other from the Nos.5 and 2 Brow districts. To do this, it was necessary to build two air crossings, one over the No.5 Brow and the other over the No.2 Brow, and to drive a road in the coal for some 130 yards, along which the return air from the Orrell Four Foot to the overcast over No.5 Brow would be led.

In September 1931, Mr. William Roberts, H.M. Sub-Inspector of Mines, made an inspection of the No.5 Brow District and reported that he found an air crossing in the process of being built across No.5 Brow below the doors, which at that date were near the top of that brow and that those doors were later to be taken out. Unfortunately, this intended rearrangement of the ventilation had not been made prior to the explosion although everything had been completed for that purpose. The air crossing over No.2 Brow had been finished about a fortnight previously.

Shots were fired in the coal by duly appointed shotfirers during the morning and night shifts and by the firemen during the afternoon shifts. The explosive, Hawkite No.2, was supplied free to the colliers who took it underground in locked canisters. Only the shotfirers only had a key. The roads in the pit were dusted with carbonate of lime, between three and four pounds of this dust being spread per ton of coal drawn. The No.12 Level from No.5 Brow to the shunt at No.8 Brow was so treated on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday the 8th, 9th, and 10th November before the explosion. Three samples which were taken along the No.12 Level between No.5 Brow and No. 8 Brow from the floor, roof and sides contained 45, 9 and 19 percent of combustible matter respectively, while three samples taken from between Nos.8 and 9 Brows on that level showed 66 per cent of combustible matter in the sample taken from the floor, and 60 percent in the samples taken from the roof and sides. The results of the tests showed that it was only in the area on the inbye side of the No.8 Brow that dust comparatively high in combustible matter was found after the explosion.

The manager, underlooker, firemen and shotlighters used “Protector” flame safety lamps and the leading collier in each working place was provided with a similar lamp for gas testing purposes. He also had an “Oldham” electric lamp and this type of lamp was used by all other workers underground. The shaft siding to the top of the No.2 Brow was lighted by fixed electric lights. Two of the eight persons making each cage load were searched at the surface for matches and other prohibited articles and every person was again searched at the shaft bottom.

An electrical haulage engine was placed near to the No.9 shaft bottom for working the endless rope haulage to the South Level and South Brow. All other haulage engines in the mine are driven by compressed air. Two that were situated on the rise side of the South Level, hauled the sets of tubs up the No.2 and No.5 Brows by the main rope. One, situated on the North side of No.5 Brow opposite the entrance to No.12 Level in No.5 Brow district worked a single track endless rope haulage along that level. The return wheel was fixed some 18 to 20 yards beyond the top of the No.8 Brow. There were also, in that district, on the high side of the No.12 Level, small hauling engines at the top of Nos.7, 8, and 9 and 9A Brows for hauling the full tubs up those brows. Signalling on all the mechanical haulage roads was by means of electrical bells except in No.7 and 9 and 9A Brows. The battery in each circuit consisted of several Leclanche cells and the conductors were of galvanized iron wire and the other copper covered with vulcanized rubber. Pushes were provided at places from which signals had or might have to be given and it was intended that the signals should be given only by means of these pushes. Detailed inspection made after the explosion by Mr. James Cowan, Junior Electrical Inspector of Mines, found that the conductors in the No.5 Brow, which were not affected by the explosion showed many bare places on the conductor which should have been covered. About ten of these bare places occurred where joints he been made, but the remainder, about 60, was bare for about two and a half to three inches with the insulating material at each end of the bare part with clean cut edges. These appeared to have been made deliberately in order that signals might be given by bridging the conductors. This appeared to have been the practice, as Mr. Cowan found only two pushes on this brow and one of these had no cover. He also found insulation missing on the No.12 Level.

In the No.12 Level engine haulage room Mr. Cowan saw a “Wigan Gastight” bell which was in circuit with the conductors that led along the level and the casing of this bell was broken and held on by a joiner’s wood screw. The battery consisted of three Leclanche cells connected in series to the bell push. A push on the No.12 Level near the entrance to the level was a water-tight push as manufactured but the cover was missing and thus the contacts within the push exposed. Mr. Cowan examined the electrical signalling apparatus in the No.8 Brow and found parts were torn down and there was no bell push at the bottom of the brow and bared wires as been travelled down the brow. With regard to the condition of the conductor which was intended to be covered it was recorded that William Ackers, whose duties were confined to the care of the signalling units and telephones in the mine said that pushes were installed at 30 to 40 yard intervals and it would not have been possible, to his knowledge, to give signals other than by using a push. He said he knew of no bare places on the covered conductors and that he had never seen a push without a cover. He said that the bell at the hauling engine at the top of the No.8 Brow was a “Wigan 1920 bell” with a battery of eight three pint Leclanche cells. This was corroborated by Arthur Holland who drove the engine during the morning shift.

Holland said that he had sometimes had to go down the No.8 Brow sometimes because the signal wires had got crossed and the bell kept ringing. This occurred about twice a week and he had to go down the brow and uncross the wires and he put a road nail underneath the insulated wire to keep it in its place. This was always at the same place and the fireman on his shift, William Marsh, heard the bell ringing continuously just as he had and when this had occurred. Marsh thought that wires were crossed and sometimes Marsh had told him to have a look. Marsh said that this had occurred. Albert Tootle, who drove the hauling engine working the endless rope haulage on No.12 level, said the bell at that engine sometimes rang continuously. He acknowledged that the push might be sticking but as soon as a boy was sent to remedy the situation, the bell ceased to ring.

William Maltby, an assistant electrician at the No.9 Colliery gave evidence that he had seen pushes occasionally without their covers and had seen places where the insulation had come off. He agreed with Mr. Cowan that were only two pushes on No.5 Brow and that there were places where the insulation was missing but he did not agree that either of the two pushed was without a cover. Mr. Maltby said that about two pushes about a fortnight came out of the mine for repair, usually a new cover or new screws. The reason that the screws were missing was that people stole them and covers went astray because if a push was sticking people took the cover off in order to signal more easily. He added that these incidents were reported to the manager.

Mr. Ralph Brown, the electrician at the No.9 Colliery, who had been at the colliery for fourteen years, said that when he came, both the conductors in the signalling wires were bare and that the change to insulated ones. Bells with metal cases were introduced at the same time, these complied with the regulations. He disclaimed any responsibility for the signalling system underground but he received three or four times a week reports from William Ackers and from the firemen of missing covers. He regarded this as a serious matter both from a safety and an expense point of view. He had a serious discussion about it with the manager and the undermanager.

The scene for the explosion was set and the twenty-five victims of the disaster were working and the night shift when at about 2 a.m. an explosion occurred about 1,200 yards from the pit bottom in the No.5 district where twenty-eight of the one hundred and five night shift workers were engaged.

News of the disaster reached those in the vicinity of the pit early on the Saturday morning. One man who lived about three hundred yards from the pit was awake at the time of the explosion but heard nothing and the first indication that he had that something was wrong was a knocking at his door and the voice of a woman saying, “Number Nine’s gone up”.

Rescue gangs from a wide area rushed to the Colliery including the main Brigade from the Lancashire and Cheshire Owners Rescue Station based at How Bridge, Atherton. Teams of volunteers also arrived form the Maypole Colliery, Wigan Junction Colliery, Richard Evans and Co., Bryn Hall, Collins Green, Wigan Coal Company and Crompton and Shawcross Collieries and relays from these brigades went underground with breathing apparatus throughout Saturday and Sunday until the last body was brought to the surface. A number of ambulances from Wigan Borough and Police were rushed to the scene and remained standing at the pithead in the hope that there would be survivors.

In addition to the Rescue Brigades stoical heroism was shown by numbers of others who volunteered to go down the pit without breathing apparatus and assist in the operations. Among these was Mr. John Latham, the manager of the Colliery, who had a narrow escape while trying to drag a young man to safety. He was overcome by the gas and rescued in an exhausted state.

At the pit head, beshawled women and silent men waited at the pit head as news of the disaster spread. They remained throughout Sunday and well into the night despite the cold which blew from the colliery buildings. Mothers and sisters stood in groups some with children in their arms, hoping against hope. Even when the victims were brought out of the pit there was no sound from the crowd.

Below ground, the first that was known of the explosion was a terrible flash of flame which despite its force spent itself in a surprisingly short distance due to the area having been dusted down with stone dust. Immediately after the news of the disaster spread through the pit, the workers organised themselves into rescue parties and heedless of their own safety, rushed to the aid of their stricken colleges. Four men were brought out alive but despite the efforts of the rescue workers in the gas filled workings, it was not until late on Sunday night that the rest of the bodies could be got out and brought to the surface.

Mr. Peter Bullough the undermanager also took part in the rescue attempts and although he was an elderly man he worked without rest for eleven hours and was also brought out of the pit in an exhausted state at three o’clock on Sunday afternoon and had to be revived with oxygen.

There was no lack of expert assistance and advice including Sir Henry Walker, the Chief Inspector of Mines and Mr. Gordon McDonald the M.P. for Ince went below ground. Mr. Christopher McBride was in charge of the first operations at the pit bottom. Dr. James, of Ashton, hurried to the scene and was reported to be in his bedroom slippers when he arrived at the pit.

The papers of the time reported that there had been a gob fire near the scene and that shot firing had taken place earlier. Evidence of burns was found on several disfigured bodies and on the injured and there had been a number of heavy falls of rock several of the dead having been buried. The coal seam is five feet thick in this district where the majority of the dead were located.

By 9 a.m. three bodies had been recovered and at that time it was thought that the death toll would be ten but it became increasingly obvious that the toll would be greater than this. At one o’clock twelve bodies had been recovered and they were brought out of the pit wrapped in field grey and red blankets to the sawmill which had been hastily improvised as a mortuary where they were placed to await identification.

Most of the bodies had the appearance of being gassed and two seem to have been stricken down whilst the rest were heaving coal in their arms. In all sixteen bodies were recovered on Saturday. The work went on all night and by Sunday, twenty-two bodies had been recovered and the remaining three, Clough, Lodge and Beddows were under a heavy fall in the shunt.

The three were found lying near each other and Beddows was recovered just before 9 o’clock and he was lying near his engine and covered by a fall of debris. The fall was sixteen yards long and the task was rendered all the more difficult owing to the dangerous nature of the roof which was sprinkling and a heave fall might have occurred at any moment. Beddows was seen lying near his engine but before we could get him out the roof came down again and the pick and shovel work had to begin again.

There were many messages of sympathy from all over the country. Lord Derby visited the Colliery Offices at Bryn on the Sunday following the explosion and expressed his sympathy and he conveyed a message of sympathy from the King which read:

The Queen and I are much distressed to hear of the disaster at the Garswood Hall Colliery and the serious loss of life involved. Please convey to the deceased relatives our heartfelt sympathy and make inquiries on your behalf on the progress of the injured.

George RI.

Copies of this message of sympathy were presented to the families and relatives of the dead.

Other messages of condolence came from the Prime Minister to Henry Walker, the Chief Inspector of Mines:

Will you please express my heartfelt sympathy with the families of those who have been lost in the disastrous explosion at Garswood Hall Colliery early this morning. I am deeply grieved to hear of the terrible explosion.

There was also a telegram from Mr. Ernest Brown the Minister for Mines to Mr. Walker which read:

Deeply grieved to hear of the serious loss of life at the No.9 Garswood Hall colliery this morning. Please convey my since sympathy to the families and friends of those who lost their lives and keep me informed of the progress of the injured and of the rescue operations.

Mr. E. Edwards the Secretary of the Miners Federation of Great Britain sent a message to Mr. Edmondson, the proprietor of the colliery, which said:

Convey my heartfelt condolences to all as a result of the explosion.

Mr. G. Lansbury M.P., the leader of the opposition also sent a message and Lord Colwyn who was a former Chairman of the Company, who had resigned only a few weeks before said – “I am terribly grieved. I feel the deepest sympathy for the relatives of the dead men”.

The news of the accident came as a sad blow for there had not been a serious accident at the colliery for almost thirty years. There was an official statement issued on the Saturday which stated:

The Management regrets to report that a slight explosion occurred in the No.9 pit Edge Green Colliery, Ashton-in-Makerfield. There were one hundred men in the mine but the explosion was confined to one district in the No.5 brow and we regret to say that there were few survivors from this district. The death toll will probably be twenty-three or twenty-four. Fortunately, the explosion was not caused by fire but there was a considerable amount of firedamp. The causes of the disaster are as yet unknown beyond the fact that an explosion occurred and the cause of the disaster has not yet been established.

Those men who had got out of the pit alive had graphic stories to tell. John W. Devenny, one of the injured was interviewed at the Wigan Infirmary suffering from shock and he said that he heard a noise which sounded like a crump and the fireman came up and asked him if he had heard anything and he went away to investigate. The fireman later telephoned for some men to go along.

A rescue worker, George Henry Jones, of York Street, Ashton-in-Makerfield, a packer who was at work three miles away in the Arley mine was called upon for the rescue operations. They came across a shotlighter who was moaning on the ground and took him away.

At a colliers working place, they found three men lying on the ground lying on the ground of which two were dead. Jones was asked to go and get help and as he went along he saw three lamps but no trace of any men. He reported this to the undermanager who found that a large fall fourteen yards long had occurred. The undermanager had to get over this and by the afternoon a number of bodies had been recovered from under the fall and the bodies were not recovered until an enormous amount of debris had been removed.

One of the early volunteers of the rescue work, John Fearnley aged 25 years, a collier of Old Road, Ashton-in-Makerfield, had an amazing escape. He had rushed from the Arley mine when news of the disaster spread. When the first volunteers retreated from a wall of gas it was discovered that he was missing. His family was waiting at the pit head. He was last seen in the early hours of Sunday morning and as the day wore on it was four o’clock when the news came that Fearnley had been discovered alive.

A Doctor went down the pit and took a bottle of brandy and the ambulance took Fearnley to Wigan Infirmary. It appears that he went to the scene of the explosion when he was overcome by the gas and became unconscious. He remembered nothing more until he found he was sitting up against a pit prop with the debris of the roof around him but he was too weak to move and it was very quiet in this region of the dead. He saw a glimmer of lamps and his spirits rose. He called as loudly as he could in his enfeebled state and was rescued. At the Infirmary he had little recollection of what had happened:

I found myself alone and there was very little to do except sit there and wait. My lamp had gone out I was in total darkness and I drifted in and out of conciseness and I was afraid that I would not be found. I looked down the drawing road and was overjoyed to see a light move across and knew that the party was near. One or two more lights appeared and they heard me and got me out of the mine.

More details of the conditions below ground and the work done by the men and conditions were revealed at the inquiry into the disaster which took place some months later.

The notes on the victims were made at the pit head as they were brought out of the pit and examined by the Doctors. The notes appeared in the report of the official inquiry and were typical of the injuries received by men who had been in a mine explosion.

The medical report on the victims was made by Dr. S.W.Fisher, H.M. Medical Inspector of Mines attended the mine on the day of the explosion and the following day. He visited Wigan Infirmary and thereby the consent of the Hospital Authorities, he was allowed to see the men George Dallimore and Patrick Quinn but they were so ill he made no attempt to speak to them.

Dr. Fishers’ evidence pointed to the site of the greatest flame during the first explosion being on the No.12 Level. When giving his evidence, Dr. Fisher bore testimony to the assistance given to him by the ambulance men and to the satisfactory nature of the ambulance arrangements.

Those who died were:

- Edward Mitchell aged 55 years, a married man of 7, Russell Street, Wigan who was a pit setters labourer. He had burns to the lips and superficial on the face singed hair.

- Joseph Pimblett aged 60 years. A married man of 6, Golborne Road, Ashton-in-Makerfield a bricksetter. He had Superficial burns and numerous small cuts.

- Ernest Yates aged 22 years, a single, of 315, Bolton Road., Ashton-in-Makerfield. He had a small burn on his right shoulder.

- Joseph Lowe aged 64 years. A married man of Birch View, Edge Green, Ashton-in-Makerfield who was the colliery fireman. He had superficial burns.

- Joseph Hill aged 39 years of 249, Edge Green Lane, Golborne who was a collier. He had extensive superficial burns.

- Joe Uel Prescott aged 43 years. A single man of Edge Green Lane, Golborne who was a collier. He had superficial burns and no other injuries.

- Frederick Hughes aged 50 years a married man who lived at 67, Golborne Road, Ashton-in Makerfield who was a collier and had superficial burns and no other injuries.

- John Pownall aged 56 years. A married man of 46 Church Street, Golborne who was a winner. He had superficial burns and no other injuries.

- William Campbell aged 41 years of 3, Leigh Street, Golborne. He had extensive and superficial burns and no other injuries.

- Henry Pennington. A married man of 8, Dane St., Golborne and was a collier, aged 44 years. He had extensive and superficial burns and no other injuries.

- Gordon Rowland Bell aged 52 years. A married man of 6, Helen Street, Golborne who was a collier. He had superficial burns and a scalp wound.

- Peter Thornton aged 42 years, of 14, Child Street, Golborne who was a collier. He had extensive and superficial burns and no other injuries.

- William Catterall aged 50 years. He had superficial burns and abrasions to the left side of the face as though he had fallen heavily in the dust. He was a married man of 34, Golborne Street, Ashton-in-Makerfield who was a collier.

- Thomas Woolham aged 37 years who had superficial burns and no other injuries. He was a married man of 4, Church Street, Downall Green who was a collier.

- James Broughton Brogan aged 41 years. A married man of 26, Liverpool Road, Ashton-in-Makerfield who was a collier. He had superficial burns abrasions to the head and a small scalp wound at the back of the head.

- Harold Woodcock aged 29 years. He had extensive burns and not other injuries. He was a married man of 12, Edge Green Street, Ashton who was a collier.

- Thomas Lyons aged 20 years, a single man who was a haulage hand of 34, Dan Lane, Golborne. Burned from head to foot, very sever over the lower part of the thighs back and front. Deep cut three inches long to the bone on the right side of the forehead caused postmortem, bone not fractured at the site of injury. Swelling over left upper arm and shoulder.

- Alfred Gill aged 26 years. A married man of 54, Warrington Road, Platt Bridge who was a collier. He had extensive and superficial burns over the arms calves abdomen and over the back but no other injuries.

- William Carless aged 18 years a single man of 9, Liley Lane, Ashton who was a haulage hand. He was burnt on both legs right below the knee and inside the thigh. He was burnt on the front left thigh and leg hair singed both arms burnt mostly on the right no other injuries. On his back his right thigh extensively burnt posterior (over scapula region) large deeper burnt area 12 inches by 6 inches, roughly the upper part of his back also burnt. He had no other injuries.

- William Kenny aged 30 years. A single collier of 12, School Street, Golborne who had superficial burns from head to foot. Feet protected by clogs no other injuries.

- Austin McDonald aged 28 years. A single collier of 46, York Road, Ashton-in-Makerfield. His face and hair singed and extensive superficial burns to the arms and chest and legs. Deeper degree of burning over the whole of the right side of the chest also to the inner side of the thigh and legs. There was a blister containing clear fluid at the back of the waist and a deep cut over the lower third of his right shin.

- Herbert Hughes aged 23 years who lived with his father who was also killed at 67, Golborne Road, Ashton-in-Makerfield. He had superficial and extensive burns all over the body. Four small wounds cut over the left eye, comminuted fracture of his left elbow.

- Joseph Clough aged 20 years. A drawer who was single and had burns to the forearms and hands, thighs and legs and eyelashes singed. Simple fracture of the lower third left leg.

- Fred Lodge aged 36 years. He had burns confined to his back and a simple fracture to the lower left third of the left leg. He was a single man of 8, Druid Street, Ashton-in-Makerfield who was a drawer,

- Hector Beddows. An engine boy aged 16 years of 39, North Street, Ashton-in-Makerfield who was a drawer. He had both hands severely burnt hair and eyebrows singed burning passing along the thighs body pitted where it was pressed against the floor. A piece of coal about three-quarters of an inch was driven into the left upper arm. Badly crushed compound fracture of the right leg caused in the opinion of the doctor after death.

In every case, carbon monoxide gas was the immediate cause of death although some burning was very extensive. Any other injuries were comparatively slight and would not themselves cause death with the exception of the injuries of Beddows, and possibly Clough and Lodge.

Those who had been got out of the mine alive but injured and were taken to Wigan Infirmary were:

- George Dallimore aged 50 years. He had superficial burns to the arms, chest and head. Moustache singed and hair as well. He was asleep and unable to be questioned. Tannic acid treatment was administered at the colliery and continued in the hospital. He died on the 18th. November 1932,

- Patrick Quinn aged 55 years, a shotfirer of Golborne Road who had compound fractures to both legs dislocation of the right ankle lacerated ear fractured jaw. He was too ill to be questioned in the hospital. There were visual signs of carbon monoxide poisoning which was shown by the pigmentation to the face and lips, was absent. This could have been due to the time that had elapsed. He died 19th. November 1932,

- William Williams aged 22 years of Bank Street, Golborne who suffered from shock and the effects of gas and John Devenny of Colliery Cottage, Edge Green, Golborne who suffered from the effects of gas and shock.

- George Gilmore aged 50 years of Victoria Road, Platt Bridge who had burns to the face and shock.

The victims were buried at St. Thomas’ C. of E., Ashton-in-Makerfield, St. Oswald’s, Ashton-in-Makerfield and Downall Green Parish Church.

The time within which the investigations of the area affected by the explosion could be made was cut short by a decision made by the Managing Director of the Company, Mr. J.H. Edmondson to erect stoppings at certain points. Mr. Edmondson made this decision solely on the grounds of safety.

At 7 a.m. on the morning following the explosion Mr. C.M. Coope, manager of the Lyme Colliery belonging to Messrs. Evans and Co. was in the No.5 Brow district and found a peculiar smell near a pack at the bottom of the No.7 Brow. To Mr. Thompson, the only thing this smell conveyed to him was that there was “that there might be something left behind by the first or second explosion”. It was not anything like as strong as the “gob stink” which, in his experience, came from heating in the Ravin Seam but it did suggest the possibility of spontaneous combustion. Mr. Coope did not express any opinion as to what it might mean. Mr. Thompson went to the surface at about 8 p.m. and saw Mr. Whitehead and Mr. Sword, who had not been underground that morning. He reported the finding of the smell which he told them he thought “Was the parafinny smell that you get in the very early stages on any heating”. He did not tell Mr. Whitehead and Sword that there was any heating. He did not think there was heating but it was a sign that there might be something in the very early stages. He was, as he said “trying to be ultra-cautious if possible, knowing there had been two explosions in the district”.

Mr. Coope, on leaving the mine, conveyed his views to Mr. F.B. Lawson, the general manager of the Haydock Collieries of Messrs. Evans and Co. who had hurried to the scene of the disaster and had been underground on the day of the explosion. An investigation was thereupon made on the spot by Mr. Whitehead, Sword, Bullough, McBride and Coatesworth and later in the day by Mr. Walker, Mr. Charlton, Mr. Stevenson, who was a past manager of the No.9 Garswood Hall Colliery. In no case did anyone consider the smell to indicate the presence of gob fire or of heating. Mr. Latham, the manager, did not associate the smell with a heating in the goaf but said that the idea of a possible heating having been put into his head by other people, made him very anxious, knowing as he did that there was a good deal of firedamp in the mine.

The opinions of Mr. Stevenson and Mr. Bullough, as men of great experience in this mine, carried much weight in reassuring Mr. Walker and he was also reassured by the favourable results os analyses of the mine air for carbon monoxide content taken on the day of the explosion and the following day by Mr. Ivor Gibson, Assistant Director of the Birmingham Research Laboratory and his assistant Dr. T.D. Jones,

When the explosion occurred, Mr Edmondson had been ill in bed for a week, but he came to the Colliery Office but was not able to go underground. Mr. Walker was present in the office on the following day of the explosion before his underground, when Mr. F.B. Lawson, having had Mr. Coope’s message, first suggested that the smell might indicate a heating in the gob and that there was on this account further risk of another explosion with possible loss of life.

When Mr. Walker returned to the surface, Mr. Edmondson had left the colliery so Mr. Walker was not able to advise him, personally. Mr. Walker was fully reassured of the position. Mr. Edmondson was ill, being so concerned lest any further disaster should occur had however given orders for the district to be sealed off.

It was unfortunate, that while the putting in of certain of the first stoppings was mutually agreed between Mr. Charlton and Mr. Edmondson, the final sealing off of the district was done without discussion between representatives of all who were interested. During the examination of the explosion area after the event, a damaged flame safety lamp was found and this was carefully considered as a possible source of ignition. The results of the investigations made on the lamp that was found at the bottom of the No.9 Brow. The lamp was called, “Damaged Flame Lamp No.62”. This damaged lamp was found on the evening of the day following the explosion when Messrs. Whittaker, a surveyor, Simmons, assistant surveyor and Messrs. Bloor and Roberts, H.M. Sub-Inspector of Mines were engaged in taking measurements of the district to make a plan showing the effects of the explosion. The lamp when found apparently minus its glass the gauzes being down in the oil vessel. When examined later in the Office of the Colliery the gauzes were lifted and a piece of glass fell out. The lamp was examined at the Mines Department Testing Station, Sheffield by the Superintending Testing Officer Captain C.B. Charlton who submitted his findings to the Inquiry.

His report no the particular lamp came to the following conclusion:

With the exception of lamp 62 all the other lamps both flame and electric were in good condition and as received were incapable of igniting firedamp.

I could find no evidence that lamp 62 had been burning in an atmosphere contain firedamp.

The electric bells and the signalling equipment in the mine also came under great scrutiny. Two electric signalling bells as described below were sent to Captain Platt for the purpose of ascertaining, in respect of either or both, whether the spark produced by breaking the external circuit and at the trembler contacts whilst the bell was ringing was capable of igniting firedamp.

A “1920” bell by which the signals given on the No.8 Brow, were indicated to the haulage engine driver at the high side of the No.12 Level. A “Wigan Gastite” bell taken from the haulage engine on the north side of the No.5 Brow opposite to the entrance to the No.12 Level. The results of Captain Platt’s experiments were that the spark it produced did ignite an explosive mixture of firedamp and air. Captain Platt also made tests to find out whether the pushes installed in conjunction with the bells were flameproof. With the cover of the push removed, the spark produced at the make and break contact, when the push was operated, ignited firedamp.

In a series of tests which Captain Platt made to determine whether the actual cause of the switch was flameproof, he found that when it was completely assembled, as intended by the maker, an ignition of gas within the case would not pass the flame to the outside atmosphere. If, however the small rubber gasket at the gland of the switch case and a small hexagon nut retaining the gasket on the position were removed then a flame from within the case could pass to and ignite gas (8.3 percent firedamp) in the outer atmosphere. This occurred even if the line wire was in position through the gland. Ignitions were not however obtained every time and were as Captain Platt described them “Chancy”.

All the possible causes of the explosion were examined. They were shotfiring, a fire due to spontaneous combustion, to which the Ravin Seam was subject; a match struck for someone smoking, sparks or heat due to falling rock, a damaged safety lamp and electricity.

Examining these possible causes, there was no evidence of any sort that a shot had been fired immediately prior to the explosion. The evidence given by Mr. Ivon Graham and of Dr. T.D. Jones, eliminated any suspicion that a fire due to spontaneous combustion might have been the cause. There was a careful inspection of the area for matches or smoking material that failed to reveal any signs of such articles and there was no evidence of a fall having occurred prior to the explosion and the roof was neither shale nor rock. Two falls were found on the No.12 Level after the explosion but as burned bodies were recovered from beneath each of them; it is evident that they occurred after the explosion.

There remained a damaged safety lamp and means of ignition caused by electricity. Mr. D. Coatesworth, H.M. Junior Inspector of Mines, expressed the opinion that the point of origin of the first explosion was in the No.12 Level, somewhere between Nos.7 and 8 Brows and considered that an explosive mixture of firedamp and air accumulated in that level because the ventilation current was more obstructed by the restrictions in the path that it was intended to follow than it was by the numerous brattice sheets placed across No.12 Level. He considered that this accumulation was ignited either at the bell-push or at the wires, while a signal was being given to move the haulage rope on No.12 Level. He had heard evidence that there was no pushes in the mine which did no have covers and that it was extremely exceptional for pushes to be found without covers but he had also heard the evidence of Mr. Cowan who found pushes without covers and when in the north district subsequent to the explosion he had himself seen nine pushes four of which had no covers and the fifth otherwise defective.

The second explosion in Mr. Coatesworth’s opinion was caused by something left burning by the first but he was not prepared to say definitely where that burning was. He thought that it was at the fall at the top of the No.8 brow but it might have been elsewhere. The suggestion that the damaged safety lamp had been the cause of the explosion was dismissed by Mr. Coatesworth. Mr. L.T. McBride, Senior Inspector of Mines, agreed with this opinion.

There was now only the one other cause, namely electricity, which was in use in the No.5 Brow district at the time of the explosion for the purpose of giving signals. The evidence was quite clear that Harold Hesketh, the driver of the haulage engine working he haulage along No.12 Level received a signal from the gangrider who was in the shunt on that level between No.7 an 8 Brow “to stretch up” and with in a short interval, Hesketh gave that interval as 13 seconds and then as 18 seconds, he heard a report like a shot which came out of the No.12 Level and was followed by dust also out of that level. There was no doubt that an electric spark made when that signal was given, ignited firedamp which had collected in the shunt on No.12 Level. Mr Charlton thought that firedamp would accumulate in a caunch or ripping and even if a strong current of air is passing beneath and would remain there.

During the Inquiry, suspicions became fastened on the brickwork wall with a door into which had been erected in No.12 Level in an endeavour to prevent air leaking from the intake outbye long this level. There were no less than ten brattice sheets across No.12 Level in addition to the brock wall which had had a door in to but in which the door had been replaced by a brattice sheet because the movement of the hauling engine kept the door open.

The manager, who said that he knew that district better than the fireman, described the condition of the brattice sheets and of the brick was in the No.12 Level and said that the brattices were good, fairly heavy, and three or four layers thick. They were swung from the roof bar and fastened to the roof bar and swung down and fastened at their sides as well. In regard to the brick wall, he said it went up to the roof and it had a door frame, about four feet by four feet from which the door was taken away and replaced by a brattice sheet.

Mr. Latham described the brattice sheets to be good but there was still a leakage of air along the No.12 Level but that leakage was very small. Some air leaked air through three brattice sheets between Nos.9 and 8 Brows and turned down No.8 Brow that some went on through the sheet over the door frame in the brick wall and the brattice sheet between Nos.8 and 7 brows and turned down No.7 brow. The remainder of the leakage went on and through the two brattice sheets between Nos.7 and 6 Brows and turned down No.6 Brow.

Keeping these conditions in view and remembering that the seam dipped one in five and a half to the goaf, there had been no difficulty whatever with firedamp until the goaf was formed. The air had to travel a long way and therefore the air current sluggish. Was it natural that firedamp would creep along the roof from the goaf up into the No.12 Level in spite of the “very small” leakage of air along that level of which Mr. Latham gave evidence? The answer could only be “Yes”.

Such behaviour of firedamp is within the knowledge of mining men with experience of the working of inclined seams. What Manager who had tried to course the air down an inclined face had not experienced the great difficulty of preventing the firedamp given off that face from accumulating at the top end?

Two questions remained to be answered, namely:

1) Why did not the firemen discover firedamp in No 12 level?

2) At what height from the ground was the signalling push in the shunt in that level?

The two firemen, Marsh and Storer and the gangrider Albert Woodcock on No.12 Level were recalled to give evidence on the last day of the Inquiry. Storer was called first and he was asked to describe exactly the route followed when making an inspection of the No5 brow district. This he did. He was asked to show exactly where on that route he made the theses for gas and this he did. Marsh was also called and he was asked to do the same having given his replies it is clear from the replies of the firemen that neither of them made any teats for firedamp on the No. 12 level. According to the evidence given by Mr. Latham he did not expect the firemen to take any test on No. 12 level except at the far end.

It may be said that the drawers and the others working at the No.12 Level would have smelled firedamp if it had accumulated there. The reply to this is that on the Sunday following the explosion, there were places in the No.5 Brow were there was so much firedamp that safety lamps had, if they were to be kept alight, to be kept close to the floor, and yet that firedamp even to those on the lookout for it was not smelled. There certainly was a smell at the bottom of the No.7 Brow on that day but even to sense that smell, it was necessary to be within a very small radius of a certain spot.

The effect of the presence and movement of the drawers and of tubs passing to and fro along the No.12 Level would be to mix the firedamp and air between the brattice sheet. Albert Woodcock followed the fireman; Marsh in the witness box on the last day of the inquiry and on being asked to indicate in what position he had would be when he was pressing the push in the shunt on the No.12 Level he raised his hand to a point slightly above his head. He was five foot eleven inches tall.

Coupling with these facts the evidence by the electricians during the inquiry in reference to the constantly recurring occasions on which covers of such pushes had to be replaced or repaired, the apparently casual manner in which, and the frequent intervals at which, the underground electrician made an inspection of the signalling apparatus. The evidence was given by Mr. Cowan in regard to the numerous bare places evidently made for the purpose of bringing the conductors together for the purpose of giving signals and the fact that on that day of the explosion I myself saw an uncovered electric bell-push on No.5 Brow nearby Hesketh’s hauling engine I have no hesitation in reporting that the first explosion caused by the ignition of firedamp which had accumulated in No.12 Level and the cause of the ignition was the open sparking signal given by Hesketh to “Stretch up”.

It may well be asked if the explosion has occurred as I have said why did one not occur before? At the foot of the No.9 Brow there was marked a break in the roof. That break was along the low side of and touching the pillar of coal and ran along by that side of that pillar towards No.8 brow.

On the last day of the inquiry, a witness, Francis Smith, of whose important evidence would not have been presented but for the fact that Mr. Latham, when giving his evidence, said that he had not been given certain information by Smith. Smith said that when he was working at the bottom of the No.9 Brow about 9 o’clock on the night of Friday 11th. November, that is some five hours previous to the explosion, the waste below the No.9 Brow was weighting but there was no beak in the roof. The break was thereafter the explosion and if firedamp came off at that break, as no doubt it did, it would rest on the sluggish current of air, keep to the high side of the place which was the side at which it was emerging at the break pass along No.8 Brow up that brow to No.12 Level and accumulate in the space provided between the roof and the level of the lintel of the door frame in the brick wall. This course of events may have been the answer to the question but it has also to be remembered that Captain Platt in his evidence in reference to his experiments with the electric bells said that he did not get an ignition of firedamp every time he made and broke the external circuit.

With the accumulation of firedamp on the No.12 Level was ignited there would be a train of flame right back to the point from which it was emerging and coal dust would be stirred up partially consumed resulting in the production of the deadly carbon monoxide gas. George Dallimore alone of the 26 persons in this part of the No.5 Brow escaped and he owed his escape to the fact that at the moment he was working in the intake air at the entrance to the district.

The flame died out on the No.12 Level in an outbye direction namely owing to the release afforded by the openings to the left and right up and down No.7 Brow and the presence of stone dust prevented the burning of coal dust.

On the inbye sides of the No.8 Brow there were openings left and right up and down No.9 Brow but that part and all parts inbye had not been dusted with stone and the coal dust prevalent in those parts and especially prevalent, because the workings were “broken” workings, would and did extend the area over which the flame spread.

The second explosion was due to a fire left as a result of the first and that fire was in the shunt in No 12 level and to have been extinguished by a heavy fall which was found later in that shunt. It will be remembered that in his evidence Hesketh described he appearance of the atmosphere at the outbye end of the No.12 Level after the first explosion as being like mist, whereas he Daly and Duffy were near the entrance to that level sometime later before the second explosion occurred they describe the atmosphere emerging from that level at that time as black fumes with a peculiar smell as something burning.

The two doors on the No.5 Brow were blown open by the first explosion and remained open after Quinn and Hesketh soon after the explosion had passed through then when on their way to the No.5 Brow. Later they were closed by Duffy, Daly and Hesketh and a second explosion occurred within a few minutes thereafter. It may be, as was suggested by Mr. Coatesworth and probably was the fact that the second explosion was hastened by the closing of these two doors. It was certain that if they had been blown open by the first explosion and remained open and so allowed fresh air to go directly down No.5 Brow and into No.2 Brow the men in that district would all have been killed by the carbon monoxide in the afterdamp carried on to them. As it was they had a narrow escape.

The Official Report began by commenting on the conditions in the colliery before the explosion. The scheme of ventilation was bad and it was recognised that the manager evidently recognised that this was the case.

Long before the working out of the pillars was begun, Mr. Latham had started to make preparations with a view to an alteration. The Inspector of Mines commented:

It was unfortunate that he did not press on with the work. It could have been completed long before the removal of the pillars formed I the stret work began and it is surprising that when firedamp began to give trouble he did not then immediately complete his scheme it is also surprising that the Agent, Mr. Whitehead id not press him to do so instead of telling him, as he did to put more brattices across No.12 Level.

The new scheme would have given each district its own air supply and have got rid of the several doors erected on the haulage brows. The air current at the time of the explosion had to find its way as best it could along the edge of the goaf which was always a dangerous practice. The travelable airways should have been kept open either by the use of chocks or stone buildings.

It would have been wise for Mr. Whitehead and Mr. Latham to have taken Mr. Charlton into their confidence when they found themselves in difficulties they should have either have gone to see him or asked him to visit the colliery to discuss the position. If they had done so the advice which Mr. Charlton with his long experience could have given then would have been of great value.

On this point, Mr. Walker commented:

On many occasions, I have tried to impress upon those in charge of the working of mines that when in difficulty their proper course was to take the Inspectors into their confidence to put their troubles clearly before them and to ask for their help. The Inspectors are at all times anxious to be of assistance and especially in times of their difficulties.

The signalling system came under great scrutiny at the inquiry. It was found to be unsafe in the presence of firedamp. It could be thought that the No.5 Brow on the inbye side of the doors of the No.12 Level were not parts of the mine in which inflammable gas, was likely to occur in quantity sufficient to be dangerous and that the General Regulations did not apply, but this could not be the case in regard to the foot on No 8 brow.

The position does not seem to have been understood. The system in use had been described, two conductors one insulated and one bare, pushes and bells which were thought to be flameproof and batteries of Leclanche cells. Had the bells and pushes been flameproof and maintained in that condition and had signals been given by means only of bell pushes, then the system was safe. But the bells and pushes, even if they were flameproof when new, were not maintained in that condition and signals, in view of the numerous bare places on the insulated conductor, obviously were used other than by using the bell-pushes. The bells themselves were not safe. They were of such construction that the spark given when the circuit was made and then broken was capable of igniting firedamp.

It had not been realised that to ensure safety under all conditions when using electric bells, the bells themselves must be of such construction, that the spark given at any point within the bell should have been incapable of igniting firedamp.

Many types of bell were available which had been tested and certified by the Mines Department as safe. Their safety was achieved by incorporating a device that absorbed part of the energy which otherwise would be released on breaking the circuit at the point at which the signal was given.

Mr. Walker commented:

The position is complicated and not easy to understand. It is necessary that it should be cleaned up and steps are being taken by the Mines Department to this end.

When an explosion occurred in a mine it was natural for those men who had not been affected, without waiting for the arrival of the Rescue Brigades to enter the area covered by the explosion with the object of giving aid to any of their comrades who may be alive. They looked for firedamp and so long as they can keep a light going forward, were unaware of the much greater danger from the carbon monoxide. It was realised that it would be hopeless to try to prevent men acting in this manner but the officials of every mine should have knowledge of this danger and the means by which men unequipped with rescue apparatus can guard against it.

This point was mentioned during the Inquiry and at the close, Mr Walker made some observations upon it which were to the effect that in mines in which an explosion is possible, mice or small birds should be kept in every district for the use of those who attempt rescue operations before the arrival of a Rescue Brigade.

He went on to say:

The suggestion may seem, no doubt, fantastic, but I know no other means of protecting men in such circumstances. It does not appear efficient, as is now required to keep birds at the surface of every mine for the would-be rescuers are themselves already underground and forget or may never have known of the birds kept at the surface. Where birds kept underground their presence would be known and the reason for their presence would become common knowledge.

The Official Inquiry into the Edge Green Explosion finished with these words:

In conclusion, I desire to record my deep appreciation of the courtesy shown to me by the representative parties to the Inquiry and by all those who attended the Inquiry.

I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your Obedient Servant,

HENRY WALKER.

REFERENCES

Report on the causes and circumstances attending the explosion which occurred at the Edge Green No.9 Colliery, Ashton-in-Makerfield, Lancashire, on the 12th November 1932 by Sir Henry Walker, C.B.E., LL.D. H.M. Chief Inspector of Mines.

Colliery Guardian, 18th November, p.951, 9th December 1932, p.1093, 16th December, p.1139, 23rd December, p.1857.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

Return to previous page